Chapter 12: Less Government, Lower Taxes, and Deregulation (2014)

It would appear that today we are faced with the same kind of situation we faced in the 1930s when the boom and bust cycle of economic instability came to an end, and the economy stagnated for want of a distribution of income capable of providing the domestic mass markets needed to achieve full employment in the absence of a speculative bubble. Because of the 1) heroic actions of the Federal Reserve in dealing with the financial crisis, 2) size of the government in the economy today, and 3) the social insurance system put in place in the wake of the Great Depression we have not suffered the dire consequences of the tragedy we went through in the 1930s. Just the same, the situation is ominous:

Even though the unemployment rate reached a high of only 10.0% in October of 2009 and fell to 6.7% by the end of 2013, this fall was accompanied by a 4.1 percentage point fall in the labor force participation rate as literally millions of potential workers were forced out of the labor force.

Total debt stood at 351% of GDP in 2013. This level of debt is simply staggering. Even an average rate of interest of 2% on a debt of this magnitude would require a transfer from debtor to creditor in interest payments equal to 7.0% of GDP. If the average rate of interest were to increase to 5% it would require a transfer equal to 17.6% of GDP. This would be comparable to the 16.7% of GDP the federal government collected in taxes in 2013.

The concentration of income at the top 10% of the income distribution had increased to 48% of total income by 2012 with 19% concentrated at the top 1%. This concentration of income was actually above the level of concentration that existed leading up to the Crash of 1929 and that persisted throughout the Great Depression.

Most disturbing of all is the fact that the average real income of the bottom 90% has stagnated since 1973 and by 2012 had, in fact, fallen below the level the bottom 90% had earned in 1966.

The Conservative Response

What is the response of Conservatives to the fall in income received by the bottom 90% since 1973? For the Conservative, it’s all so simple: It’s the government, stupid! If the government would just get out of the way and let free markets reign lower taxes, less government, and deregulation would bring prosperity to all. It’s the magic of free markets that brings prosperity to all, not the government!

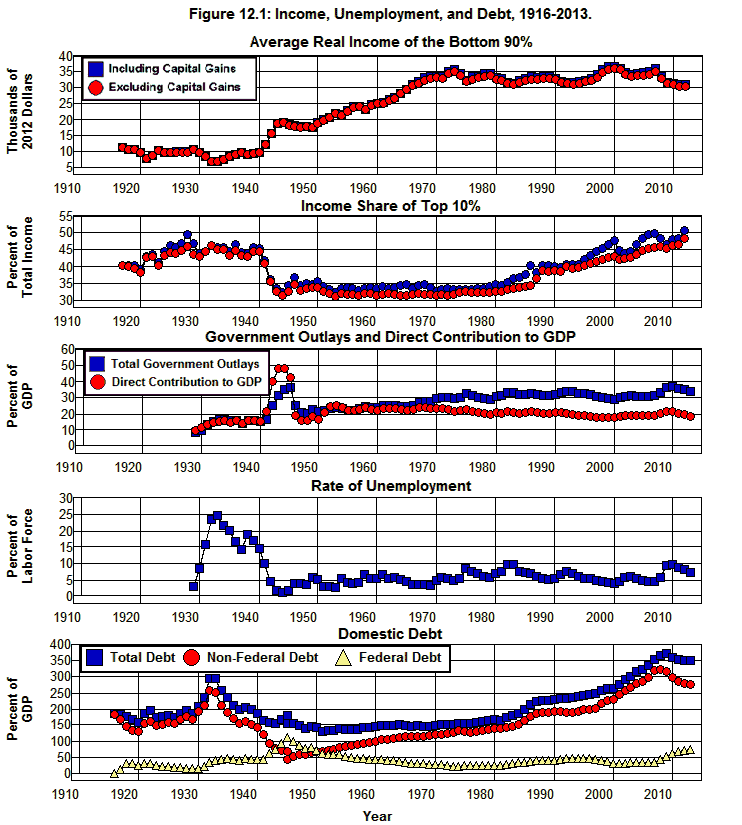

The relevance of this response to the real-world problems we face today can be evaluated within the context of Figure 1. This figure shows the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution, the Income Share of the Top 10%, total Government Outlays and Direct Contribution to GDP, the Rate of Unemployment, and Domestic Debt in the United States from 1916 through 2013.

Source: The World Top Incomes Database, Bureau of Economic Analysis (1 1.1.5 3.1 3.2 3.3), Historical Statistics of the U.S. (Cj872 Ca10), Federal Reserve (L.1), Economic Report of the President, 1966 (D17).

Even a casual look at this figure makes it clear that during the era of lower taxes, less government, and less regulation that reigned from 1917 through 1933 there was no increase at all in the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution. Even during the New Deal the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% barely increased from 1933 through 1940. It wasn’t until after the government literally took over the economic system during World War II, drafted 8.5 million soldiers into the armed services, and purchased the potential mass-produced output that could not be sold to the private sector during the 1930s that the unemployment problem of the 1930s was solved and the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% began to increase significantly. And it wasn’t until after the Non-Federal Debt ratio and the Income Share of the Top 10% fell during the war, and Government Outlays and Expenditures doubled relative to what they were in the 1920s following the war that the domestic mass markets needed to sustain mass production were able to grow at the pace needed to maintain full employment in the absence of speculative bubbles and dramatic increases in Total Debt.

It is also worth noting that the deleveraging of Non-Federal Debt that took place from 141% of GDP in 1940 to 67% in 1945 took place within an environment in which the top marginal tax rate had been increased to 94%, total government expenditures had increased to over 40% of GDP, and the rationing of consumer goods and strict controls on investment expenditures gave households and firms little choice but to pay down their debts as their incomes increased dramatically during the war. Even then, actual non-federal debt increased from $145 billion in 1940 to $153 billion in 1945. It was the dramatic increase in GDP (from $103 billion in 1940 to $228 billion in 1945), brought about by the increase in government expenditures during the war that made it possible for Non-Federal Debt as a percent of GDP to fall. This feat was not accomplished through the magical powers of free markets to bring balance back into the economy through the liquidation of households and firms—the kind of liquidation that took place from 1929 through 1933 that drove the economy into depths of catastrophe.

The simple fact is this: The economy did not recover from the Great Depression. What happened was the New Deal came along, and the government completely took over the economic system during World War II. The economic system that emerged from the New Deal and World War II was no longer the system of lower taxes, less government, less regulation that had existed in the 1920s—the system that had, in fact, led us into the Great Depression. The economic system that emerged from the New Deal and World War II was a system of higher taxes, more government, and strict regulation, and it was this system of higher taxes, more government, and strict regulation that led us out of the Great Depression and into the economic prosperity we experienced following World War II.

When we seek to see how this prosperity was accomplished, we find that it was

the fall in the concentration of income brought about by government policies during and following World War II,

the more than doubling of the government’s Direct Contribution to GDP following the war over what it had been in 1920s,

the growth of government sponsored social insurance programs put in place during the New Deal that were expanded after the war,

the high tax structure put in place by the government during the war that was, for the most part, kept in place after the war,

the financial regulatory system put in place by the government in the 1930s that was expanded after the war, and

the international regulatory system embodied in the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944 that was put in place by an agreement between the governments of the world

that made it possible for the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution to increase from $6,940 at the beginning of the New Deal to $34,956 in 1973. And it is clear—at least it should be clear to anyone who thinks about it—that the government policies that increased the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution played a crucial role in creating the prosperity and economic stability that followed World War II.

There is just no way all of the automobiles and refrigerators and washing machines and air conditioners and toasters and TVs and the countless other mass-produced goods and services that were produced following World War II could have been sold in the absence of a dramatic increase in debt if the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% had not increased in the way it did. Who would have purchased all of that mass-produced stuff if the concentration of income at the top and the average real income at the bottom had, instead, reverted back to their 1917 through 1940 trends shown in Figure 1? What would it have taken to maintain a fully employed economy if this reversion had taken place? How long would that prosperity have lasted if the purchase of those goods and services had been financed through increasing debt rather than having been paid for out of increasing income?

In other words, it was the government that brought us out of the Great Depression and made the prosperity that followed World War II possible, not the magical workings of Free-Market Capitalism with lower taxes, less government, and deregulation. This is reality! This is what actually happened! Conservative ideologues who deny this reality and think that, somehow, we can live happily ever after if we return to the lower taxes, less government, and less regulated system of the 1920s—the system that led us into the depths of the Great Depression and provided no growth at all in the income of the vast majority of our population—live in a delusional world of make-believe that is a figment of their own imaginations.

World War II was hardly an optimal solution to the problems caused by the concentration of income and the overwhelming burden of debt created by the fraudulent, reckless, and irresponsible behavior of those in charge of our financial institutions in the 1920s. It should be obvious that it would have been better to have solved these problems through a somewhat less massive government intervention to build up our public infrastructure by providing substantial improvements in our transportation, public utility, public health, public sanitation, and public educational systems than by drafting millions of people into the military and producing massive quantities of war materials. And it should also be obvious that it makes more sense today to mobilize our fiscal resources by increasing taxes and government expenditures and waging a war on our deteriorating physical infrastructure than waiting for a real war to justify the mobilization of these resources (as we did during the 1930s) or manufacturing a real war to justify this mobilization (as we did at the beginning of the twenty-first century). All of these things should be obvious, yet, none are obvious to the free-market ideologue whose only vision for the future is lower taxes, less government, deregulation, and sending our troops abroad.

It also should be obvious that if Conservatives were to honestly place the blame on the government where blame is due they would be forced to point their fingers at the government’s following their advice in instituting the policy changes that took place following 1973—our abandonment of capital controls embodied in the Bretton Woods Agreement, the tax cuts of the 1980s and 2000s, the decline in government’s Direct Contribution to GDP following 1973, and the financial deregulation that took place at their behest. It was these policy changes that led to

the stagnation of the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution since 1973,

the increases in our current account deficits that have occurred since the 1970s,

the dependence of our economy on a continually increasing Total Debt relative to income to provide the mass markets needed to sustain employment as the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% failed to increase,

the concomitant dramatic increase in Total Debt relative to income and in the Income Share of the Top 10% of the income distribution,

the boom and bust economy that created this increase in Total Debt relative to income that facilitated the increase in the income Share of the Top 10%,

the financial crisis that began in 2007 and culminated in the Crash of 2008, and

the resulting fall in the Average Real Income of the Bottom 90% of the income distribution to below where it stood in 1966.

For thirty years following World War II our democratically elected government ignored the advice of Conservative ideologues and made huge investments in our society. It built our Interstate Highway System. It expanded our educational systems through grants in aid and such programs as the GI Bill and National Defense Education Act as it subsidized the education of the best and the brightest among us who, in turn, provided the scientific research that led to the tremendous advances in technology we have seen in the past seventy years. It also made huge investments in our physical infrastructure and in our social-insurance system. The end result of these public investments was a highly educated and productive labor force, a tremendous increase in our physical infrastructure, and a social environment that provided the social capital that made it possible for our economic, political, and social systems to flourish. If these systems are to continue to flourish, the physical infrastructure and social capital that made this possible in the past must not only be maintained, it must be allowed to grow, and this cannot be accomplished today without a substantial increase in government expenditures. (Kleinbard)

Allowing our physical infrastructure and social capital to grow not only increases productivity, it expands our economic system into areas that provide huge social benefits—education, police and fire protection, regulation, public health, garbage and trash collection, scientific and technological research, social insurance, and the construction of physical infrastructure such as streets, roads, highways, bridges, subways, trains, ports, water treatment and sanitization facilities, schools, public lighting, hospitals, parks, beaches, and other recreation facilities—that balance our economic system in areas that cannot be provided efficiently by the private sector. (Amy Musgrave Lindert Kleinbard) In addition, if we were to use our fiscal resources to restructure student and mortgage debt it would help to reduce the non-federal debt ratio in a way that would stimulate the economy. (Mian)

Balancing our economic system in this way has the added effect of decreasing the concentration of income and bolstering our mass markets as income is transferred through our tax system to those areas in the public sector that provide the kinds of huge economic and social benefits the private enterprise cannot provide—benefits that are essential to the economic prosperity and the social wellbeing of our society. (Amy Musgrave Lindert Kleinbard)

Since the 1970s we have followed the advice of Conservative ideologues by lowering taxes on the wealthy and increasing taxes on the not so wealthy as we dismantled our regulatory systems and cut back on social welfare and other government programs that serve the common good and promote the general Welfare. In the process we have consumed a substantial portion of the public investments we had accumulated in the past as we allowed those investments to deteriate. The result has been a fall in income for the vast majority of our population and a growing divisiveness within our society as we have fallen behind in educating our children, our physical infrastructure has deteriorated, the rate of increase in productivity has fallen, our healthcare system has become the least efficient among the advanced countries of the world, we have achieved the highest incarceration rate in the world, and fraud has run rampant in our financial system leading to the worst economic disaster since the Great Depression. (Kleinbard)

These are the rewards we have reaped from following the advice of Conservative ideologues whose declared objective is to destroy our government and whose followers have pledged to assist in this destruction. If we are to survive this crisis with our basic social institutions intact and without a continuing stagnation or fall in the standard of living of a major portion of our population we must reject the dogmatism of ideologues and rescind their policies through the kinds of government action outlined above.

And above all, we must raise taxes!

On The Need to Raise Taxes

If those who benefit the most from our economic system do not pay back in taxes enough to rebuild the physical infrastructure and social capital that were consumed in the process of reaping the benefits they have gained from our political, social, and economic systems and, at the same time, pay back enough to allow our physical infrastructure and social capital to grow, there is little hope for the future. And it is important to note that this does not mean just the top one or two percent of the income distribution. It means that everyone who is capable of making a contribution toward this end must do their part. If this is not done we will continue to consume the physical infrastructure and social capital left to us by previous generations, and in failing to replenish those resources and not allowing them to grow, we will diminish the economic possibilities for our children and grandchildren. (Kleinbard Martin Sachs)

On Increasing Personal Taxes

National income in the United States was $14,577 billion in 2013, and total federal outlays came to $3,456 billion. This means the total tax liability created by the OMB’s projected 10.6% deficit for 2019 amounts to 2.5% of GDP. There was a surplus in the federal budget equal to 2.4% of GDP in 2000 before the massive 2001-2003 Bush tax cuts, before the invasion of Iraq, and before those who ran our financial institutions devastated our economy. Does it really make sense to make dramatic cuts in Social Security or Medicare or to dismantle a major portion of the rest of the federal government rather than rescind the tax cuts in this act and return to the tax structure we had in 2000? We could even increase taxes by the extra 1% or 2% of our national income that would be required to replenish the physical infrastructure and social capital we have consumed over the past thirty-five years and allow these kinds of public investments to grow for the benefit of our children and grandchildren if we wanted to. (Kleinbard Martin Bruenig Waldman Kleinbard) [57]

If we are to solve our federal deficit/debt problem and maintain our social-insurance programs with a functioning government, the place to begin is with the 2001-2005 tax cuts by 1) rescinding the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (that made the bulk of the 2001-2005 tax cuts permanent), 2) adding additional brackets at the top of the income tax structure, and 3) eliminating the special treatment of dividends and of capital gains to the extent that capital gains are not the result of an increase in the general price level and are on assets that have been held for less than five or ten years.

Eliminating the special treatment of dividends and, especially, capital gains, when combined with 1) a financial transaction tax on trades in financial instruments, 2) the elimination of the carried interest loophole, and 3) an increase in the top marginal tax brackets would have the added benefit of reducing the single most powerful incentive that motivates the fraudulent, reckless, and irresponsible behaviors that lead to financial crises and, ultimately, to the kind of economic stagnation we are in the midst of today—namely, the ability to make massive fortunes from these kinds of behaviors. (Waldman Piketty) And adding a substantial increase in estate and wealth taxes to this mix will have the added benefit of reducing the tendency toward the establishment of dynastic wealth which tends to increase the concentration of income. (Piketty Summers)

And most important, these tax measures, combined with the elimination of the unearned income exclusion and income caps on payroll taxes, will have the added benefit of strengthening our mass markets to the extent they reduce the need to increase taxes on the rest of the income distribution and, thereby, allow the purchasing power of the vast majority of the population to grow. At the same time, to the extent these measures reduce deficits and the federal debt they will also reduce the transfer burden from taxpayers to those who hold government bonds. (Fieldhouse Diamond Sides Waldman Mian Domhoff Piketty Summers)

It is important to realize, however, that we are not talking about a free lunch here. We cannot replenish the physical infrastructure and social capital we have consumed over the past thirty-five years and allow these kinds of public investments to grow for the benefit of our children and grandchildren simply by taxing the rich. Everyone who is capable of making a contribution toward this end must do their part. (Kleinbard Martin Sachs Kleinbard)[58]

On Taxing Corporations

When it comes to the need to increase taxes on corporations, it is worth emphasizing that corporations benefit from and consume government services to a much greater extent than other businesses. Corporations depend crucially on our legal and law enforcement systems to protect their property rights and to settle disputes among corporations and between corporations and their customers, employees, and the government.

Corporations benefit substantially from the government’s providing and enforcing copyright and patent protections and from the limited liability protection provided by the government. Corporations also benefit substantially from our public transportation systems and from the educated workforce our public education systems provide. And a major reason our defense budget is so large is to protect the foreign interests of American corporations throughout the world. There are reasons why international corporations locate in countries whose governments provide highly developed legal, law enforcement, transportation, public education, and national defense systems.[59]

Increasing taxes on corporations will not only help to compensate society for the disproportionate amount of government services that corporations consume and from which corporations benefit so greatly, given the skewed distribution of corporate ownership toward the wealthy, increasing corporate taxes will also have the added effect of strengthening our mass markets to the extent it reduces the need to increase taxes on the rest of the income distribution and, thereby, will help to maintain the domestic purchasing power of the vast majority of the population who do not own a significant amount of corporate stock, but, again, this does not mean that the rest of us can have a free ride. Everyone who is capable of making a contribution toward this end must do their part. (Kleinbard Martin Sachs Kleinbard)

The Case against Raising Taxes

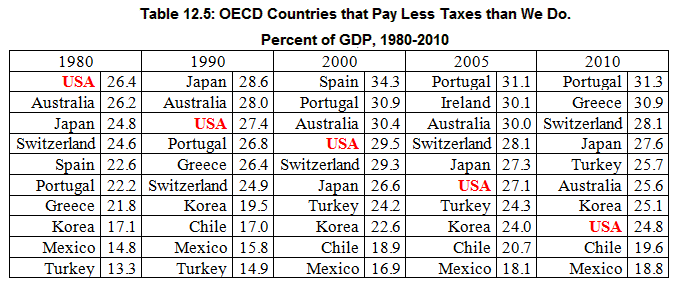

The response from those who are waging their own private war against government is that our taxes are too high, and we can’t afford them. This claim does not survive even a casual look at the data. Table 12.5 shows how the United State's ranking among the 34 OECD countries has changed since 1980 in terms the percentage of gross income (GDP) paid in taxes.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Comparative Tables.

We moved from tenth from the bottom on this list to third from the bottom over the previous thirty years. Among the advanced countries of the world only Chile and Mexico paid less in taxes as a percent of their gross income than we did in 2010.[60]

There is no reason to believe we are overtaxed and can't afford the taxes needed to fund the essential services that can only be provided by government. Does it really make sense to follow the lead of any of the countries on this list as we allow our physical infrastructure and social capital to depreciate and our economic system to stagnate? Japan is only able to maintain its distributions of income by producing for export with a current account surplus and has been unable to achieve full employment for twenty odd years now. Australia would appear to be in the midst of a housing bubble that is fueled by its current account deficit as it sells off its real estate to foreigners, and Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Chile, Korea, and Mexico have not exactly set sterling examples of the kinds of societies we should be striving to emulate. The only reasonable alternative on this list is Switzerland, a rather small country with a distribution of income that is far less concentrated than ours in spite of its current account surplus. (Kleinbard Martin Kleinbard)

Reregulating the Financial System

It will, of course, also be necessary to reregulate our financial system if we are to keep our financial institutions from creating the kinds of economic disasters that unregulated financial institutions have created throughout history. At the very least we must:

re-enact Glass-Steagall to eliminate the kinds conflicts of interests inherent in conglomerate mega-bank financial institutions,

break up those financial institutions that are "too big to fail" through substantial increases in capital requirements,

provide for direct regulation of hedge funds and the markets for repurchase agreements by giving regulators the power to set capital requirements for hedge funds and margin requirements for repurchase agreements,

eliminate safe harbor provisions in collateralized debt contracts, (Morrison) and

eliminate the over-the-counter markets for derivatives by forcing derivative trading onto exchanges with clearinghouses whenever possible, and when this is impractical, requiring that these contracts be backed by substantial reserves.

These are the minimum actions required to keep those in charge of our financial institutions from creating in the future the kind of economic catastrophes they have created in the past when unrestrained by government regulation.

Simply passing laws, however, is not enough. Government regulation begins with the law, but it ends with the regulators. It was the blind faith in free-market ideology that was the primary cause of the financial crisis that began in 2007, not the absence of legislation. The Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act (HOEPA) passed 1994 gave the Federal Reserve the absolute authority to regulate the mortgage market. Enforcing the laws against predatory lending practices, enforcing strict underwriting standards for mortgage loans, and setting maximum loan to value ratios on mortgages would have prevented the housing bubble that came into being in the 2000s. The Federal Reserve had the absolute authority to do all of these things under HOEPA, but the ideological faith in free markets to regulate themselves on the part of regulators, the administrations, and the Congress kept the Fed from doing so. Had they done so, there would have been no housing bubble. Unfortunately, given the concentration of income that existed at the time, it would have also led to prolonged unemployment in the absence of the kinds of government actions I am advocating here. (Natter WSFC Bair)

In addition, the regulators could have sought legislation to bring Money Market Mutual Funds and repurchase agreements under the purview of depository regulators during the Reagan administration, but ideology stood in the way. They also could have sought legislation to extend the regulatory authority of the Security and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission to regulate hedge funds and the over-the-counter markets for Credit Default Swaps and other derivatives during the Clinton administration, but, again, ideology stood in the way.

Until the delusional view of reality embodied in the failed nineteenth-century ideology of Free-Market Capitalism is replaced in the minds of regulators, administrations, Congress, and the body politic with a pragmatic view of financial regulation that recognizes the need for the government to rein in and control the speculative and fraudulent proclivities of the financial sector, there is little hope of our being able to avoid similar economic catastrophes in the future or for the standard of living of the vast majority of the population to improve.

Reregulating International Exchange

We must also come to grips with the current account deficits we have experienced over the past thirty-five years. These deficits are the direct result of foreign goods being undervalued in our domestic markets which gives importers an unfair advantage in competing with domestic producers. This undermines the mass markets for domestically produced goods and places a serious drag on our economy. To the extent this drag has contributed to the need for a rising debt to maintain employment, it has also contributed to the instability of the American economy.

The deficits in our current account followed in the wake of the 1973 decision to abandon the managed international exchange system contained in the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement and to replace it with what became known as the Washington Consensus which championed unrestricted international finance and trade. The result has proved to be recurring international financial crises in addition to the manipulation of exchange rates by countries that desire to undervalue their currency in order to build up their international reserves, stimulate their economies, or maintain the concentration of income within their societies. (Bergsten)

It is, of course, neither desirable nor feasible to return to the fixed exchange systems of the Gold Standard or the managed fixed exchange system embodied in the Bretton Woods Agreement,[61] but speculation in the international exchange markets must be curbed, and our current account deficits must come to an end. This can be accomplished by reinstituting the capital controls implicit in the Bretton Woods Agreement and, if need be, placing tariffs or other trade sanctions on the imports from countries that attempt to manipulate their exchange rates to undervalue their currencies. (Crotty Bhagwati Wilson EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

Reregulating Collective Bargaining

Collective bargaining played a major role in creating the domestic mass markets that allowed our economic system to flourish following World War II. Not only did collective bargaining provide a countervailing force against the power of corporations in setting wages in unionized industries, it also facilitated the increase in wages in nonunionized industries by motivating antiunion employers to move toward the standards set by union contracts in order to meet social norms and reduce the threat of unionization. (Galbraith Western Cowie)

With the founding of the Business Roundtable in 1972, the growth of corporate funded Political Action Committees and think tanks in the 1970s, and the creation of the Democratic Leadership Council in 1985, organized labor lost its political influence in Washington. As a result, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has been under funded and dominated by appointees who have failed in their duty to protect the rights of employees since the 1970s. This has facilitated a systematic attack on unions that resulted in a fall in the fraction of the employed persons that belongs to unions from 24.6% in 1970 to 11.5% in 2003.[62] Union membership fell from its high of 21.0 million in 1979 to 15.8 million in 2003 in spite of the fact that the number of employed persons increased by 38 million workers during this period.[63] (Western Cowie Tope Domhoff Frank)

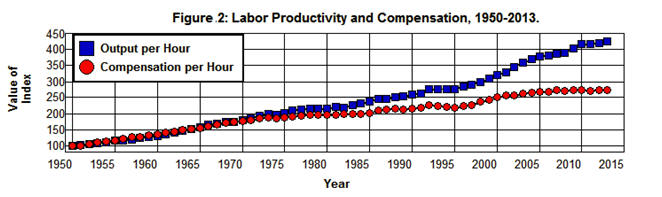

The cumulative effects of the undermining of collective bargaining through the systematic attack on unions and the failure of the NLRB to protect the rights of employees that began in the 1970s can be seen in Figure 2 which shows the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s labor productivity Output per Hour and real Compensation per Hour indices (1950=100) for all employed persons from 1950 through 2013.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Productivity and Costs.

These two indices tracked each other quite closely through the 1960s as wages (Compensation per Hour) increased as labor’s productivity (Output per Hour) increased. They then began to diverge in the 1970s as increases in wages began to lag behind increases in productivity to the point where hardly any of the benefits from the increase in labor’s productivity were shared with labor during the 2000s, and there was no increase at all in wages as productivity increased by 10% from 2007 through 2013.

This failure of wages to keep pace with labor’s productivity may seem like a good idea to those who believe they can benefit from this by keeping their wage costs low, but this runs into what economists refer to as The Fallacy of Composition—the idea that if something is beneficial when one person does it, it must be beneficial if everyone does it. While it may be beneficial for an individual business to hold down its wage costs relative to those of its competitors, a general fall in wages—or even a failure of wages to keep pace with increases in productivity—is, in fact, a disaster for the country as a whole. After all, wages provide the backbone of our domestic mass markets. The concomitant rise in profits that occurs when the general wage level fails to keep pace with increases in productivity undermines our domestic mass markets, and, as a result, the real investment opportunities that could have been created by the expansion of these markets cannot come into being. As the real investment opportunities that could have come into being if wages had continued to rise with productivity fail to materialize, we are left with only imaginary investment opportunities—created in the midst of speculative bubbles—to bolster our economy.

The shift in bargaining power from employees to corporations that accompanied the decline in unions played a major role in the increase in the concentration of income that has undermined our domestic mass markets. (Western Cowie Tope Domhoff) If we are to restore our domestic mass markets, the balance in bargaining power that existed in the 1950s and 1960s—the period in which increases in wages kept pace with increases in productivity—must be restored. This cannot be done unless the NLRB begins to rigorously enforce the laws against Unfair Labor Practices. In addition, the resources of NLRB must be expanded to allow labor disputes to be resolved in a timely manner so their resolution is not allowed to drag on in litigation for years. (Cowie)

The most important change, however, that must occur if we are to restore the countervailing power of collective bargaining within our society is repeal of Section 14(b) of the Taft-Hartley Act—the so called “right-to-work” provision—that allows states to pass laws prohibiting union contracts that require employees to pay dues. Just as government could not provide the government services that are essential to the efficient functioning of society if the payment of taxes were voluntary, a union cannot provide the services that are essential to the efficient functioning of collective bargaining if the payment of union dues is made voluntary. As a result, Section 14(b) has made it impossible to implement collective bargaining effectively in right-to-work states. Not only has Section 14(b) inhibited the effectiveness of collective bargaining in right-to-work states, the migration of businesses or the threats of businesses to migrate from non-right-to-work states to right-to-work states has undermined the effectiveness of collective bargaining in non-right-to-work states as well. (Freeman) It will not be possible to have an effective system of collective bargaining in our country until the free rider problem created by Section 14(b) is eliminated.

Deleveraging Non-Federal Debt

A Non-Federal Debt ratio equal to 278% of GDP, as it was at the end of 2013, is simply unsustainable and places a serious drag on the economy. Strict regulation of financial institutions that returned financial sector debt relative to GDP back to the levels that prevailed in the 1960s or 1970s would reduce the Non-Federal Debt ratio by some 25% to 30%. It would also help if the federal government were to:

repeal the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005,[64]

make student debt dischargeable in bankruptcy,

use federal resources to restructure mortgage and student loans to reduce interest rates on these loans, and

enact federal usury laws that index the rate of interest charged on a loan to the rate of inflation plus a base rate where the maximum base rate is set between 5% and 15% depending on the type of loan.

These measures are designed to 1) help reduce the level of non-federal debt, 2) make non-federal debt more manageable, and, most important, 3) eliminate the incentives that lead to predatory lending practices. (Piketty)

It is important to remember, however, that the excessive non-federal debt to GDP ratio that existed in 1929 was not eliminated by reducing the level of non-federal debt. It was eliminated by increasing the role of government in the economic system (especially during World War II) and thereby increasing employment and output. It was the 118% increase in GDP from 1929 through 1945 as real GDP increased by 110% during that period that reduced the Non-Federal Debt ratio from 168% of GDP in 1929 to 67% in 1945, not a reduction in the level of non-federal debt. Non-federal debt fell by only 13% from 1929 through 1945. There is no reason to believe we can reduce the Non-Federal Debt ratio that exists today without a similar increase in GDP.

Summary and Conclusion

The changes in tax, regulatory, and international policies that have taken place over the past forty years have led to a situation in which, given the state of mass-production technology in our economy, the existing distribution of income and current account surpluses do not provide the mass markets needed to achieve full employment in the absence of an increase in debt relative to income. Since it would appear that we have reached a point at which a further increase in non-federal debt relative to income is unsustainable, the only way the full employment of our resources can be achieved is through 1) continually increasing our current account surplus (reducing our current account deficit) to compensate for the effects of the increased concentration of income on our domestic mass markets, 2) continually increasing federal debt relative to income to offset the effects of the increased concentration of income, or 3) reducing the concentration of income. The only alternative is to allow our domestic mass markets to shrink and, thereby, reduce our ability to utilize and benefit from mass-production technologies as our resources are transferred out of mass-production industries and into those that serve the wealthy few.

Running a continually increasing current account surplus has the effect of increasing the debts of foreigners relative to their incomes. Given the size of our economy, continually increasing the debts of foreigners relative to their incomes is akin to continually increasing domestic non-federal debt relative to our income. Neither is sustainable in the long run. The transfer burden from debtor to creditor must eventually overwhelm the system in either of these situations and lead to a financial crisis that causes the system to collapse.[65] It is no accident that the current economic crisis began at home while we were running a substantial current account deficit in the face of a speculative bubble in our domestic economy, and that this crisis has hit the hardest in those countries that were in a similar situation. (Kapner Dent Stiglitz)

As for increasing federal debt relative to income, this poses less of a problem since the federal government can always simply print the money needed to service its debt and there is no threat of default on federal debt. Just the same, doing so on a continual basis is not a long-run solution to our employment problem. A continually increasing federal debt relative to GDP must eventually overwhelm the federal budget as interest payments on the national debt grow. This will make it more and more difficult to fund essential government programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and national defense.[66] And even though the federal government has the legal right to print money it is fairly certain that doing so on a continual basis in order to meet its financial obligations will eventually destabilize the system.[67]

But the most important objection to attempting to solve our employment problem by increasing the federal debt relative to income is that it increases the transfer burden on taxpayers as increasing interest payments are transferred from taxpayers to government bondholders. Since government bondholders tend to be among the wealthiest members of our society, increasing the federal debt relative to GDP is likely to have the effect of increasing the concentration of income at the top of the income distribution and, as a result, is likely to make the fundamental problem we face worse.

The only way to avoid the kinds of financial crises we experience in 1929 and 2008 is by producing for domestic mass markets without a continually increasing debt relative to income while maintaining a reasonably balanced current account. This, in turn, requires a distribution of income capable of providing the domestic mass markets needed to purchase the full employment output that can be produced (given the state of our mass-production technologies) without the necessity of a continually increasing debt relative to income and with a reasonably balanced current account.[68] The tax, expenditure, and regulatory proposals outlined above are designed to address this problem.

The tax proposals outlined above will not solve all of our economic and social problems, but they will at least give us a tax structure that is viable and will help to stabilize the economic system. If they are combined with a dramatic increase in government expenditures designed to 1) rebuild and expand our physical infrastructure, 2) reregulate our collective bargaining and financial institutions, 3) rebuild our other regulatory agencies, 4) bolster our social insurance systems, 5) enhance the educational opportunities available to our children, and 6) restructure student and mortgage debt in a way that reduces the concentration of income, current account deficit, and non-federal debt relative to GDP, there is every reason to believe it will not only increase our physical infrastructure, social capital, the rate of economic growth, and the growth in productivity as it helps to solve our employment problem, it will also stabilize the federal debt relative to GDP, just as this debt was stabilized in the 1930s and following World War II. And it is worth emphasizing again that this cannot be achieved without increasing taxes. (Amy Musgrave Lindert Kleinbard Sachs)

It is the incongruous belief that we can have good government—and all of the essential services and benefits that only good government can provide—without collecting the taxes needed to pay for these services and benefits that led us to where we are today. The only way we can have these services and benefits is by strengthening the institutions that provide them, and the only way we can strengthen those institutions is by raising the taxes needed to provide the government services and benefits that people deserve and then demand that our elected officials provide these services and benefits: quality public education; effective public health programs; an effective and efficient personal healthcare system; safe streets and neighborhoods; a clean and safe environment; safe food, drugs, and other consumer products; safe working conditions; fair and just legal and criminal justice systems; efficient streets, roads, highways, and other forms of public transportation; an effective national defense; a viable social insurance system; and a financial system that facilitates a stable, growing economy that is not plagued by cycles of booms and busts that drive our country and people deeper and deeper into debt and lead to economic catastrophes brought on by epidemics of fraud, recklessness, and irresponsible behavior on the part of those in charge of our financial institutions.

It is only by way of collective action through a democratically elected government that we can “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” Private enterprise, guided by the profit motive cannot perform these functions within society. The only institution within society that can perform these functions is a democratically elected government. That’s what democratically elected government is for, but if we want our democratically elected government to perform these functions we have to pay the cost, and the way we pay the cost is through paying taxes. In the end, it comes down to this: Are we going to increase taxes and, thereby, enhance our government’s ability to perform the essential functions that only government can perform, or are we going to continue to follow the lower taxes, less government, and deregulation mantra of free-market ideologues and make it impossible for our government to perform these functions. (Amy Musgrave Lindert Kleinbard)

If we do not approach our non-federal debt and unemployment problems by increasing taxes and government expenditures in a way that makes it possible to deleverage the system while reducing the concentration of income and allowing our infrastructure and social capital to grow, our economic situation can only get worse.

Mass-production technologies depend upon mass markets to provide the sales needed to justify investment in these technologies. Where are the mass markets required to justify investment in these technologies supposed to come from in the absence of a mass distribution of income to support those markets? If what were formally mass markets in the developed world are converted into concentrated markets, and if—in the absence of an expansion of government—full employment is supposed to be obtained in the long run, where are the investment opportunities going to come from if not from building Mc Mansions and other monuments to serve the needs of the wealthy few? If the demand for Mc Mansions and other monuments is insufficient to provide full employment and the government must step in to fill the gap, where is the government expansion going to come from: expanding social services and infrastructure or from expanding law enforcement and national defense? Those who argue for lower taxes, less government, and deregulation are fighting to prevent the expansion of social services and infrastructure and are very much in favor of law enforcement and national defense. Continuing to follow their lead does not bode well for the future.

If we continue to follow their lead our employment problem will persist in the absence of an increasing debt relative to income, and our ability to produce will be diminished as resources are transferred out of those industries that serve the bulk of our population (those that produce for domestic mass markets) and into those that serve the wealthy few as we travel down a road that leads toward our becoming a nation of servants, groundskeepers, security guards, police officers, soldiers, and builders of pyramids as the magnificence of our cemeteries grow to rival those of Europe along with other monuments to the wealthy few.[69] In the meantime, our transportation, water and waste treatment facilities, education, regulatory, legal, and other governmental systems will continue to deteriorate, and the standard of living of the vast majority of our population will continue to stagnate or fall as the divisiveness within our society increases.

Lower taxes, less government, and deregulation caused the economic problems we face today, and more of the same is not going to solve these problems. If we are to solve these problems we must strengthen our democratic government, not weaken it. We must increase taxes, not lower them, and we must increase government expenditures as we rebuild the regulatory systems that have been dismantled since the 1970s and rebuild the physical infrastructure and social capital we have allowed to deteriorate. If we do not do these things and, instead, continue to follow the failed ideological mantra of lower taxes, less government, and deregulation we are most certainly going to end up right back where we started in the 1930s. And if the political leaders throughout the world continue to follow this failed ideological mantra and refuse to come to grips with the root causes of the worldwide economic catastrophe we face today—namely, the concentration of income at the top of the income distribution—we are likely to end up where we ended up in the 1940s. (Shirer Bullock Thames)

Endnotes

[57] I think it should be noted that while Kleinbard and Martin argue quite persuasively that it is the nature of government expenditures that are most important in determining egalitarian outcomes and not the progressivity of the tax system, the degree to which this is so depends on the extent to which income is concentrated at the top of the income distribution to begin with, and their arguments do not consider the effects of a lack of progressivity in the tax system on economic stability.( Waldman) Nevertheless, there is no reason to believe that we can fund all of the government programs that are essential to our economic and social wellbeing simply by taxing the rich. The bulk of the tax collections must come from where the bulk of the income is. In general, this means from the upper and middle income groups, especially within an egalitarian society. In a society such as ours, however, in which nearly 50% of the income goes to the Top 10% of income distribution there is plenty of room for progressivity. (Bruenig Waldman)

[58] Again, I think it should be noted that while Kleinbard and Martin argue quite persuasively that it is the nature of government expenditures that are most important in determining egalitarian outcomes and not the progressivity of the tax system, in a society such as ours in which nearly 50% of the income goes to the Top 10% of income distribution there is plenty of room for progressivity. (Bruenig Waldman)

[59] It is undoubtedly worth pointing out that to argue a corporate profits tax is unfair because it taxes income twice—once when it is earned by the corporation and a second time when it is received by stockholders in the form of dividends—is obviously fallacious. A corporation subject to a 50% corporate profit tax on a $10 million before tax profit generated from $100 million in sales would have the same after tax profit as a corporation in the same situation that paid no corporate profit tax but, instead, paid a 5% sales tax, a $5 million property tax, or a $5 million dollar tax of any other kind. In any of these situations the corporation would have the same $5 million after tax profit. The bottom line is that the same after tax profit is received by the corporation and stockholders irrespective of the kind of tax paid. A corporate profits tax is a cost of doing business, just like any other tax, and the notion that it somehow unfair because it is a double taxation of income and other taxes are not is fallacious. See A Note on Taxing Corporations.

[60] We were at the bottom of the list in 2012, but data were not available for Mexico and Chili in 2012.

[61] For an explanation of the deficiencies of these systems see a Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States, Krugman, and Krugman. For a more in depth treatment see: Skidelsky, Eichengreen, Rodrik, and Kindleberger.

[62] According to Jefferson Cowie:

“Unfair Labor Practices” (ULPs) acts, which the NLRB determined to impair workers’ rights to make free decisions about unionization, accelerated dramatically in the 1970s. In the early fifties, there had been roughly three thousand charges of illegal dismissal over union activity; by 1980, it was up over eighteen thousand. For every twenty workers voting for a union in 1980, one lost his or her job. By the end of the decade, unions, accustomed to winning two-thirds of union votes, were losing a majority of the elections that they brought before the NLRB. (Cowie)

[63] The data on union membership are taken from Gerald Mayer’s 2004 CRS Report for Congress, Union membership trends in the United States which provides estimates of membership from 1930 through 2003.

[64] See: Warren, Tabb, Morgan, Scott, and Mian.

[65] This is particularly so in a world in which international capital markets are unregulated. (Bhagwati)

[66] It is worth noting that those who wish to get rid of Social Security and Medicare use the existence of federal deficits and rising national debt as an excuse for dismantling these programs. See: Understanding the Social Security Crisis: What This Crisis Means to You, Starving The Beast, Amy, and Kleinbard.

[67] The fact that the federal government has the legal right to print money means there is no reason to believe the federal government will ever be unable to service its debt because it can always just print the money it needs if it has to. The fact that the federal government has the power to print money, however, does not mean we do not have to worry about federal debt or that “deficits don’t matter.” It makes a huge difference as to how that debt is created, and what is accomplished through the creation of that debt. See: A Note on Managing the Federal Budget.

[68] A current account deficit (or surplus), in itself, is not necessarily undesirable, particularly if it can be done without the necessity of continually increasing debt relative to income. Whether or not it is desirable depends on the circumstances in which the deficit (or surplus) arises. (Bhagwati EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

[69] Mc Mansions, yachts, opera halls, university buildings, etc. if not sarcophagi as such.