Chapter 6: The Federal Reserve and Financial Regulation

The Federal Reserve System (commonly referred to as "the Fed") was created in response to the Financial Crisis of 1907 in an attempt to deal with what was perceived at the time to be the central problem of the National Banking System, namely, the inability of this system to deal with seasonal changes in the demand for currency without placing a strain on banks and their ability to make loans. This problem was dealt with by creating the Federal Reserve System as a central bank—that is, a bank in which other banks can open deposits and from which other banks can borrow money—and by giving the Federal Reserve the power to print its own currency. At the same time, all other banks were prohibited from printing currency. (Bernanke)

The Federal Reserve thus became the lender of last resort within the banking system, willing and—given its ability to print currency—able to lend cash to other banks to meet their needs. It was believed that in addition to the ability to meet the seasonal needs of banks for cash, the Fed would also be able to eliminate financial crises by lending cash to sound banks during times of financial stress while allowing unsound banks to go out of business in an orderly fashion.

The mechanism by which the Federal Reserve functions within the financial system, and by which the Federal Reserve derives its power, is quite simple in principle and can be summarized as follows:

1. The Federal Reserve determines the amount of currency that is available to the economy.

2. The Federal Reserve also sets the reserve requirement ratio, that is, the fraction of deposits that banks must hold in the form of reserves, where reserves consist of either the currency banks have in their vaults (vault cash) or in their deposit at the Federal Reserve.

3. The non-bank public is free to determine how much of the currency made available by the Federal Reserve is held by banks and how much is held outside of the banking system.

4. Given the amount of currency made available by the Fed, and the amount of that currency the non-bank public chooses to hold outside the banking system, banks are free to expand their loans and deposits (in the manner explained in Chapter 5) as long as they can do so without violating the reserve requirement that is set by the Fed. [1]

Within this system, banks are limited in their ability to expand the amount they can borrow from their depositors as they expand the amount they lend by 1) the amount of currency the Fed makes available to the economic system, 2) the amount of this currency the non-bank public is willing to leave in banks, and 3) the reserve requirement ratio set by the Fed. As is explained below, the cornerstone of this system is the Federal Reserve’s ability to determine the amount of currency that is available to the economic system.

Controlling the Amount of Currency

The amount of currency that is available to the system is referred to as the monetary base, where the monetary base is the sum of currency in circulation (that is, currency in the hands of the non-bank public) plus the reserves held by banks, either in the form of vault cash or as deposits at the Federal Reserve.[2] The monetary base is the foundation on which the monetary system, indeed, the entire financial system rests since only currency is legal tender, which means that currency is the only form of payment that creditors must, by law, accept in the payment of a debt.

There are two ways in which the Federal Reserve can control the monetary base, hence, the amount of currency available to the economic system.

The Discount Window

The first is by making or retiring loans to banks. The Federal Reserve makes and retires loans to banks through what is referred to as the discount window where the rate of interest charged for these loans is referred to as the discount rate. All loans made by the Federal Reserve through the discount window must be fully backed by collateral supplied by the borrowing banks, and these loans are made at a discount to the face value of the collateral offered by the borrowing bank. Hence, the terms discount window and discount rate. (FRB)

When the Federal Reserve makes a loan to a bank it does so by simply crediting the reserve deposit of that bank at the Federal Reserve by the amount of the loan. As a result, the reserve component of the monetary base is increased directly by the amount of the loan. By the same token, when the Federal Reserve retires a loan previously made to a bank, the bank pays off the loan by deducting the amount of the loan from its reserve deposit at the Federal Reserve. As a result, the reserve component of the monetary base is decreased directly by the amount of the loan that is repaid.

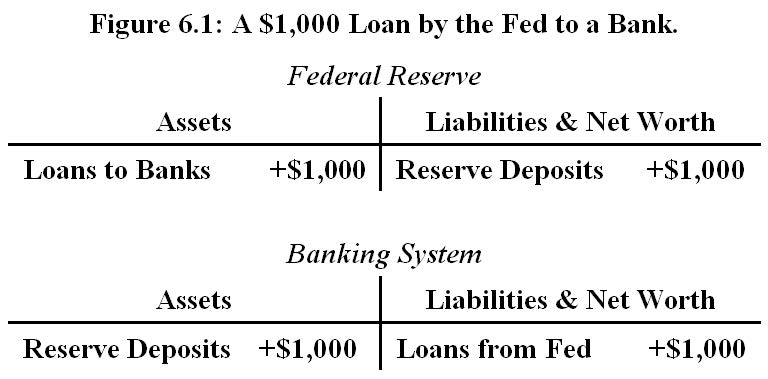

The way in which a $1,000 loan by the Fed to a commercial bank affects the financial situation of both the Fed and the banking system and, thus, changes the amount of currency available to the economic system is illustrated in Figure 6.1. When the Fed credits the amount of this loan to the Reserve Deposits of the borrowing bank, this transaction increases the Federal Reserve’s asset Loans to Banks and its liability Reserve Deposits by the amount of the loan, $1,000. At the same time, it increases the Banking System’s asset Reserve Deposits and its liability Loans from Fed by the same amount.

The fact that the Reserve Deposits in the banking system have increased by $1,000 as a result of this loan means that the monetary base—the sum of currency in circulation and reserves—has increased by this amount. Since banks can now withdraw an additional $1,000 worth of currency from their reserve account at the Federal Reserve, and the fact that the Federal Reserve has the legal right to print the currency to pay for this withdrawal,[3] means that the amount of currency available to the economy has increased by $1,000 as a result of this loan.

This process, of course, works in reverse when the loan is paid back by the bank. The Federal Reserve’s asset Loans to Banks and its liability Reserve Deposits will fall by the amount of the repayment as the bank repays the loan by allowing the Fed to deduct the amount of the repayment from the bank's reserve account. At the same time, the Banking System’s asset Reserve Deposits and its liability Loans from Fed will fall by the same amount. Thus, all of the pluses in Figure 6.1 become minuses.

The fact that the reserves in the banking system must decrease by the amount of the repayment means that the monetary base will fall by this amount as well, and there will be $1,000 less currency available to the economic system than there was before the repayment took place since banks will now be able to withdraw $1,000 less currency from their reserve accounts than they could before the loan was repaid.

Open Market Operations

The second way in which the Federal Reserve can control the monetary base is by buying or selling something. While it doesn’t matter what the Federal Reserve buys or sells, when it comes to controlling the monetary base the Federal Reserve generally restricts itself to buying or selling government securities. The decisions of the Fed to buy or sell government securities are made by the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee and are referred to as the Federal Reserve’s open market operations. (FRB)

When the Federal Reserve buys a government security, the institution that sells the security receives a check written on the Federal Reserve in the amount paid for the security. In the normal course of events, the check will be deposited in a bank, and, in turn, the bank will redeposit the check in its reserve account at the Federal Reserve. When the check is deposited in the bank’s reserve account the reserve component of the monetary base will increase by the amount of the check. [4]

Figure 6.2 illustrates the situation where the Fed purchases a $1,000 government security from a member of the non-bank public. This transaction increases the Federal Reserve asset Government Securities by the amount of the purchase, $1,000. When the member of the non-bank public deposits the check it received for the security in its bank account, the liability Bank Deposits of the Banking System increases by the amount of the check. When the bank, in turn, deposits the $1,000 check in its reserve account the asset Reserve Deposits of Banking System increases by the same amount as will the Federal Reserve liability Reserve Deposits.

Figure 6.2: A $1,000 Purchas by the Fed.

The only change that has occurred in the financial situation of the Non-Bank Public at this point is there is the exchange of one kind of asset for another—Government Securities held by the Non-Bank Public have gone down while Bank Deposits held by the Non-Bank Public have gone up by the same amount, $1,000. But the fact that the reserves in the banking system have increased by $1,000 as a result of this purchase by the Fed means that the monetary base has increased by this amount, and there is now $1,000 more currency available to the economic system than there was before this purchase took place.

By the same token, when the Federal Reserve sells a government security it will receive a check written on a commercial bank for the amount of the sale. The Federal Reserve will then deduct the amount of that check from the reserve deposit of the bank on which the check is written, and the reserve component of the monetary base will decrease by the amount of the check. The bank, in turn, will deduct the amount of the check from the account on which the check was written. As a result, all of the signs in Figure 6.2 will be reversed, and the amount of the monetary base, that is, the amount of currency available to the economic system, will be decreased accordingly.

Thus, when the Fed wants to increase the amount of currency available to the economy it can either increase the amount it lends to banks or it can purchase government securities. When the Fed wants to decrease the amount of currency available to the economy it can either reduce the amount it lends to banks or it can sell government securities.

Seasonal Demand for Currency

The ability of the Federal Reserve to control the amount of currency that is available to the economic system provided a mechanism by which the seasonal demand for currency problem that plagued the National Banking System could be eliminated. After the Federal Reserve came into being, banks were no longer forced to contract their lending as currency flowed out of the banking system in response to seasonal changes in the demand for currency. Instead, banks could borrow from the Federal Reserve or the Fed could purchase government securities from the public in order to replenish the reserves that were lost as the currency flowed out of the banks during spring planting or the fall harvest. When the planting or harvest was over and the currency flowed back into the banks, the Fed could absorb the excess currency as the loans it had made were repaid and as it sold the government securities it had purchased to meet the currency drain from banks.

It is important to note, however, that when the Federal Reserve changes the monetary base in this way it can lead to changes in the financial system that go beyond the changes indicated in Figure 6.1 and Figure 6.2 above. The Federal Reserve is not simply a passive agent that responds to the seasonal changes in the demand for currency. The Fed can change the monetary base through its lending and open market operations whether currency is flowing into or out of banks or not. As a result, the Federal Reserve has the power to affect the ability of the banking system to make loans. This gives the Federal Reserve the power to affect the credit conditions in the economic system irrespective of the seasonal demands for currency by the non-bank public.

Controlling Loans and Deposits

Consider the situation depicted in Figure 6.2 where the Fed has purchased a $1,000 government security from a member of the non-bank public and thereby increased the amount of deposits and reserves in the banking system by $1,000. Now assume that the reserve requirement ratio is, say, 10% and the banking system is fully loaned up before this transaction takes place—that is, that the actual reserves held by banks are equal to the reserves they are required to hold as determined by the size of their deposits and the reserve requirement ratio set by the Federal Reserve.

Since the reserve requirement ratio is 10%, and this transaction increased deposits by $1,000, the reserves banks are required to hold will increase by $100 (by 10% of the increase in deposits). At the same time, this transaction also increases the reserves that banks actually have by $1,000. As a result, there is $900 in excess reserves in the banking system ($1,000 increase in actual reserves minus the $100 increase in required reserves) after this transaction takes place that did not exist before this transaction took place. These excess reserves represent cash banks hold in excess of what they are required to hold given their deposits and the reserve requirement ratio—excess cash that can be used to expand the loans and deposits within the banking system.

As banks make loans to, and borrow the money back from the non-bank public in manner explained in Chapter 5, the loans and deposits in banks can grow until there are no longer excess reserves in the banking system. If there are no leakages of currency out of the banking system as this process of expansion takes place, the system will eventually reach the point depicted in Figure 6.3 where Bank Loans of Banking System and Loans from banks of the Non-Bank Public increase by an additional $9,000 bringing the increase in Bank Deposits to $10,000.

Figure 6.3: Secondary Effects of a $1,000 Purchases by the Fed from Non-Bank Public.

At this point the process of expansion must come to an end as required reserves will have increased by $1,000 (10% of the $10,000 increase in Bank Deposits), and there will no longer be excess reserves in the system. The Non-Bank Public will have increased the Bank Deposits it owns by an additional $9,000 and will have gone $9,000 deeper in debt to the banks (Bank Loans). And all of this has taken place as a result of 1) the Federal Reserve purchasing a $1,000 government Security, 2) the banking system’s willingness to lend its excess reserves, and 3) the non-bank public's unwillingness to increase the amount of currency held outside the banking system.[5]

This process works in reverse, of course, if the Federal Reserve sells a $1,000 government security. Reserves and deposits would fall by $1,000, and banks would find themselves with a $900 deficiency in reserves. Banks would then be forced to reduce their outstanding loans by $9,000 as the non-bank public paid off their debts to the banks and bank deposits would fall by an additional $9,000. All of the signs in Figure 6.3 would be reversed and there would no longer be a deficiency of reserves in the system.

The same kinds of results would be obtained if the Federal Reserve had increased its loans to banks by $1,000 in this situation instead of purchasing a government security. The only difference would be that the loan would not have directly increased deposits by $1,000, and the non-bank public would not have sold a government security. The entire $1,000 increase in reserves would be excess reserve, and banks would be able to increase their loans to the non-bank public by $10,000 instead of only $9,000. The end result would be as depicted in Figure 6.4.

Figure 6.4: Secondary Effects of a $1,ooo Loan by the Fed.

Again, if the Fed reduced its loans to banks by $1,000 instead of increased its loans by this amount all of the signs in Figure 6.4 would be reversed.

Roaring Twenties and Great Depression

While the Federal Reserve was able to solve the seasonal demand for currency problem that had plagued the National Banking System, it was not able to solve the financial crisis problem that it was hoped it would solve. The inadequacy of the Federal Reserve in this regard became painfully obvious as the economy worked its way through the roaring twenties and into the Great Depression of the 1930s.

As we saw in Chapter 4, the 1920s began with a rather steep recession in 1920-1921 followed by a speculative bubble in the real-estate market. (White) This real-estate bubble was superseded by a speculative bubble in the stock market which began in 1926 and burst in October of 1929. As real-estate and stock prices fell the recession that had began in the summer of 1929 got worse, and a banking crisis began in the fall of 1930 that didn't reach its climax until 1933 as more than 4,000 banks and savings institutions went out of business in that year alone.

As this drama unfolded it became impossible for the Federal Reserve to resolve the situation by simply providing cash to sound banks in order to save them while allowing unsound banks to go under. Even though the Fed was able to deal with the liquidity problems of banks in meeting the demands of their depositors for currency during the crisis, it was unable to deal with the solvency problems of banks that developed during the crisis. The problem was not simply that sound banks needed cash to meet their depositors’ demands for currency. The problem was that as banks contract their loans the forced sale of assets on the part of debtors throughout the system caused asset prices to fall, which, in turn, caused the value of the collateral underlying bank loans to fall below the value of the loans that had been made. (Pecora) This drove otherwise sound banks into insolvency, and banks became unsound faster than they could be saved. The result was the downward spiral described in Chapter 4 that led to the Great Depression of the 1930s. (Fisher Keynes Kindleberger Mian White)

The experience of the 1920s also revealed a number of serious deficiencies in the way the Federal Reserve was organized. Because of the inherent mistrust of government in the United States at the time the Federal Reserve was founded, there was a determined effort to decentralize power within the Federal Reserve System. Toward this end, the Federal Reserve was created as a voluntary, quasi-private institution owned by the member banks, that is, by the banks that choose to join the Federal Reserve System. And instead of creating a single bank, the country was broken up into twelve banking districts, each of which was given its own Federal Reserve Bank. Each Federal Reserve Bank was governed by a nine member board of directors, six of whom were elected by the member banks in its district and the remaining three were appointed by a seven member Federal Reserve Board that was established to oversee the system as a whole. The Secretary of the Treasury and Comptroller of the Currency served on the Federal Reserve Board ex officio and the remaining five members were appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. This arrangement insured that the individual Federal Reserve banks would be dominated by the member banks rather than by the federal government.

Even though the government-appointed Federal Reserve Board was established to oversee the system as a whole, the lines of authority and responsibility between the board and the district banks were not clearly drawn. As a result, there was no central authority within the system, and it was impossible for the Federal Reserve to pursue a unified or coherent national policy in the absence of a consensus since each of the twelve Federal Reserve district banks were free to follow their own policies irrespective of the policies of the other district banks or those of the Federal Reserve Board. (Meltzer)

To make matters worse, there were few provisions in the original Federal Reserve Act that allowed the Federal Reserve to regulate or control the kinds of behavior on the part of financial institutions that inevitably lead to financial crises. The focus of the act was on providing an elastic currency within the context of a decentralized system rather than on regulating or controlling the behavior of financial institutions as such. All of these factors combined to make it impossible for the Federal Reserve to curb the speculative behavior in the real-estate and stock markets that led up to the Crash of 1929 that ultimately led the country through a downward spiral of defaults and into the Great Depression of the 1930s. (Fisher Keynes Friedman Kindleberger Meltzer Eichengreen Bernanke Mian)

The Dynamics of Financial Instability

As was explained in Chapter 5, during periods of economic growth and prosperity the temptation to allow cash reserves to fall and to increase leverage is irresistible for many financial institutions. Poorly managed financial institutions tend to underestimate the risks of economic instability in this situation as they see the road to riches in increasing their leverage and in financing projects that pay the highest expected rates of return. Those projects inevitably turn out to be the most speculative projects that are the most at risk from economic instability. There are powerful incentives for financial institutions to finance these projects since huge fortunes can be made by those who facilitate and are able to take advantage of the speculative bubbles that are created by this kind of speculative activity. (Piketty)

In addition, while most people are honest, many are not, and in an unregulated or poorly regulated financial system opportunities for fraud abound. It is no accident that the most notorious fraud of all time was perpetrated by Charles Ponzi—the man for whom the Ponzi scheme was named—during the poorly regulated era of the roaring twenties or that the greatest Ponzi scheme of all time was perpetrated by Bernie Madoff during the recent period of deregulation. Nor is it a coincidence that the frauds of Charles Keating, Michael Milken, Ivan Boesky, Jeff Skilling, Ken Lay, Andy Fastow, and Bernie Ebbers occurred during this latter period. As these individuals and countless others have shown, fortunes can be made in the financial sector by people who fraudulently game the system, and this fraud is most dangerous when it involves banks.

Given the banking system’s ability to increase the amount it can borrow as it increase the amount it lends and the fact that a substantial portion of the banking system’s liabilities, namely its checking accounts, are payable on demand, the banking system is particularly vulnerable to a run that can bring down the entire system like a house of cards. This danger is particularly acute during prosperous times when highly leveraged, poorly (fraudulently) managed banks can earn more money than moderately leveraged, well managed banks. In this situation poorly managed banks can offer higher rates of interest to their depositors. This gives them a short-term competitive advantage in the market for bank deposits. This situation presents a dilemma to the well managed banks. If they do not follow the lead of the poorly managed banks by matching the increases in interest on their deposits the well managed banks will lose deposits to poorly managed banks. If they do match these increases they will lose money unless they also abandon their reluctance to increase their leverage and finance the kinds of riskier speculative projects being financed by the poorly managed banks. (Black Fisher Phillips Keynes) As a result, the very existence of the well managed banks is threatened in this situation if they fail to follow the lead of the poorly managed banks.[6]

In addition, there are powerful psychological and social pressures that come to bear on those who try to run a well managed bank in this situation. When others are making fortunes through what seem to be unsound practices that threaten your bottom line, it is exceedingly difficult to risk being wrong on your own by standing up and going against the tide. It is much easier to follow the crowd and risk going down together. As was noted by John Maynard Keynes some seventy-five years ago:

A sound banker, alas, is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him. (Keynes)

All of this feeds the speculation that leads to bubbles where prices are bid up to unsustainable levels and then fall precipitously as the markets crash. The problem is that when a poorly or fraudulently managed bank underestimates the risks of economic instability, funds a speculative bubble, leverages itself to dangerous levels, and induces its competitors to follow suit, the poorly managed bank threatens the stability of the entire financial system. If the bank is a particularly large or important bank, or if a relatively large number of its competitors are induced to follow suit, when the bubble bursts it can cause depositors to lose confidence in the system itself, and the ensuing panic can bring down the entire financial system as depositors try to get their money out of the banking system.

In addition, no other sector of the economy is as intricately intertwined with the rest of the economic system as is the financial sector in which banks play a central role. When this sector founders in the wake of a bursting speculative bubble it puts the entire economic system at risk. We don’t have to imagine a situation in which an unregulated or poorly regulated financial system can bring down the entire economy. This has proved to be the case throughout the history of finance and around the world whenever a financial system has become overwhelmed by a speculative bubble. (Kindleberger MacKay Skidelsky Graeber Reinhart 1819 1837 1857 1873 1893 1907 Galbraith)

Reforming the System

In 1932 the Senate Committee on Banking and Currency set out to investigate the cause of the ongoing depression. This investigation became known as the Pecora Commission after its chief counsel, Ferdinand Pecora. Pecora exposed massive levels of fraud, corruption, conflicts of interest, and incompetence on Wall Street which led to a public outcry for government regulation of the financial sector. (Moyers Galbraith) In response, Congress took a decidedly pragmatic view of financial regulation in reining in the speculative and fraudulent urges of the financial sector.

The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). It also prohibited commercial banks from undertaking investment bank and insurance company activities. This prohibition was designed to eliminate the kinds of conflicts of interests that had fostered corruption in the markets for securities in the 1920s.

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate investment banks and the stock exchanges in order to prevent fraud and corruption in the securities markets. Publicly traded corporations were required by this act to file disclosure statements with the SEC to make public important information about their firms subject to both civil and criminal penalties for false or misleading statements and for important omissions. Insider trading was also outlawed as were the stock manipulation practices such as front running, disseminating false information, and artificially trading a security to mislead investors.

The experiences of 1929 through 1033 also led to the Banking Act of 1935 which centralized control of the Federal Reserve System in the Federal Reserve Board. (Bernanke) The Federal Reserve Board was symbolically renamed the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in this act and was reconstituted as its ex officio members (the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency) were replace by members appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. At the same time, the legal authority to implement Federal Reserve policy was taken out of the hands of the individual Federal Reserve district banks and vested in a newly created Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) made up of the seven members of the Board of Governors and five of the presidents of the individual Federal Reserve district banks. Four of the five presidents serve on a rotating basis, and the president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, because of the importance of New York City banks in the financial system, was given a permanent seat on the FOMC. In addition, the Fed was given enhanced power to regulate and control speculative activities within the financial system. It was given the power to set margin requirements on loans collateralized by shares of stock, for example.

To prevent poorly or fraudulently managed banks from having a competitive advantage over well managed banks in competing for deposits, banks were prohibited from paying interest on demand deposits (i.e., checking accounts), and the maximum interest rates banks were allowed to pay on time deposits (i.e., savings accounts) was set by the Fed. To make all of this work, a comprehensive regulatory and supervisory system was put in place to ensure that banks were following the rules and not gaming the system to get around the rules.

The Maloney Act of 1938 amended the Securities Exchange Act to create Self Regulating Organizations (SROs) to provide direct oversight of securities firms under the supervision of the SEC and provided for the regulation of the Over-The-Counter (OTC) market for securities. The SEC was also authorized to impose its own capital requirements on securities firms, and in 1944 the SEC exempted from its capital rule any firm whose SRO imposed more comprehensive capital requirements.

In 1940 Congress passed the Investment Company and Investment Advisers Acts which brought mutual funds under the purview of federal regulation, and in 1956 the Bank Holding Company Act was passed restricting the actions of bank holding companies. The International Banking and Financial Institutions Regulatory and Interest Rate Control Acts were passed in 1978 to bring foreign banks within the federal regulatory framework and to establish the limits and reporting requirements for bank insider transactions. (RiskGlossary)

This regulation was designed to break the boom and bust cycle in the financial sector of the economy—which inevitably led to a boom and bust cycle in the economic system as a whole—by prohibiting the kinds of reckless and irresponsible speculative and fraudulent practices that inevitably lead to insolvency on the part of poorly and fraudulently managed banks and drove many responsibly managed banks out of business in the midst of financial crises. These measures actually worked for over fifty years to accomplish this end. Unfortunately, things began to change in the 1970s and 1980s as attitudes toward government regulation of the economic system changed.

Endnotes

[1] While this mechanism is quite simple in principle, it is somewhat more complicated in practice. The Federal Reserve System is a voluntary organization, and not all banks are members of the system. Prior to 1980, the Fed only set the reserve requirement for member banks, that is, for banks that chose to become members of the Federal Reserve System. Reserve requirements for nonmember banks were set by the states in which the nonmember banks were chartered. In addition, there are different reserve requirements for different kinds of deposits, e.g., time deposits (savings accounts) have lower reserve requirement ratios than demand deposits (checking accounts). What's more, the amount of currency banks held in bank vaults (i.e., vault cash) was not considered to be part of reserves from 1917 until 1959.

To simplify the exposition in what follows these considerations are ignored and it is assumed there is only one reserve requirement ratio that applies to all deposits and that vault cash is part of reserves. See Feinman for a history of the way reserves and reserve requirements were determined from the nineteenth century through the early 1990s and also Keister for a more technical discussion of the way in which reserve requirements are met by banks. For an explanation of the role played by gold in the financial system prior to 1973 see Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States

[2] The sum of currency in circulation and the reserves held by the banking system is sometimes referred to as High-Powered Money. Also, see the previous footnote on reserve requirements.

[3] It should be noted that the Federal Reserve’s right to print money was restricted by the requirement that the Fed keep reserves in gold (actually Gold Certificates issued by the Treasury) equal to 25% of the amount of Federal Reserve Notes outstanding. This restriction was eliminated in 1968. See: Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States.

[4] In the real world, these transfers among accounts are, of course, done electronically and do not involve the actual writing and transfer of physical checks, but it is helpful to think of the process in terms of how the transfers would occurred if they were accomplished through the use of checks as an aid to understanding the process by which the end results are obtained.[5] It should be noted that in order to simplify the exposition and bring out the basic principles involved, the ways in which the economy and other financial institutions react to changes in the amount of currency available to the economy (i.e., changes in the monetary base) are ignored in this example, and in the examples that follow. Only the hypothetical situation in which the banking system maintains zero excess reserves and there are no leakages of currency out of the banking system is considered. In the real world, of course, banks will not necessarily keep their excess reserves at zero and there will be leakages out of the banking system of the sort discussed in Figure 5.6 at the end of Chapter 5. See Tobin for a discussion of the way in which these leakages occur and excess reserves are actually determined within the financial system.[6] The nature of the problem here was succinctly put by Charles Prince, former CEO of Citigroup, in his infamous and much maligned comment in the Financial Times: "When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing.” (See Reuters)