The CDS Market and Market Efficiency

George H. Blackford © 2010

The Credit Default Swap (CDS) market is assumed to provide an efficient mechanism by which those who wish to hold securities can transfer, for a fee, the default risk implicit in holding the securities to those who are more willing to bear this risk. The purpose of this note is to examine this assumption from the perspective of market efficiency and to argue not only that the CDS market does not efficiently transfer risk, but also that the existence of this market reduces market efficiency in the financial system as a whole.

Consider a CDS with a spread [1] equal to rcds that insures an underlying corporate bond that pays an interest rate equal to r. Since the seller of the CDS pays nothing for it, and, therefore, has nothing invested in it, the spread (rcds) on the CDS is assumed to measure the pure default risk of the underlining security.

The problem is that for anyone who believes that markets are efficient there is another way to calculate the default risk associated with a corporate bond, namely, the difference between the rate paid by the bond (r) and the rate paid by a Treasury security (rt) (or the implicit rate in a combination of Treasury securities for more complicated CDSs) that has the same maturity as the bond and generates the same kind of payment stream as the bond:

(1) rts = r - rt.

where rts is the spread of the bond over the comparable Treasury security. Since the Treasury security has zero default risk and the same kind of payment stream as the corporate bond it is assumed that this spread also measure the default risk of the corporate bond.

This begs the question: Why would anyone hold a bond and pay a spread of rts (the Treasury spread) or greater for a CDS to insure against the default risk of that bond when (1) implies it is possible to earn the same rate of return (rt = r - rts) or greater on a perfectly default free Treasury security (or combination thereof)?

In the absence of some way to profit from holding the security beyond the rate of return it pays, it is obvious that no one would choose to hold the underlying security and pay rts or greater rather than hold a risk free Treasury securities. After all, the CDS itself is not risk free; there is always a possibility the seller of the CDS will default. If we set aside, for the moment, the possibility of irrationality and alternative reasons a rational buyer or seller might have for participating in the CDS market, the fact that buyers of CDSs have no reason to purchase CDSs at a price greater than or equal to the Treasury spread has a rather curious implication: It means that trading will take place in the CDS market for bonds only if the spread paid on the CDS is less than the Treasury spread.

In other words, it means that barring irrationality and alternative reasons a rational buyer or seller might have for participating in the CDS market trading will take place in the CDS market only if 1) the seller's estimate of the default risk on the underlying security is less than the market's estimate of this risk, and 2) sellers are willing to speculate against the market and bet the market is wrong.

It also means that if markets are efficient and the Treasury spread is in fact the best estimate of default risk, there must be a systematic bias toward underestimating risk on the part of sellers participating in this market, even if their estimates of this risk are equally as efficient as the market's. This follows from the fact that sellers cannot participate in the market when they err in overestimating risk relative to the market since buyers will not buy in this situation. At the same time, sellers will be able to participate in the market whenever they err in underestimating risk relative to the market since buyers will buy in this situation—the larger the error, the more willing sellers will be to buy. As a result, large underestimates cannot be offset by large overestimates in the market which must lead to a systematic bias on the part of sellers in the market toward underestimating risk.[2]

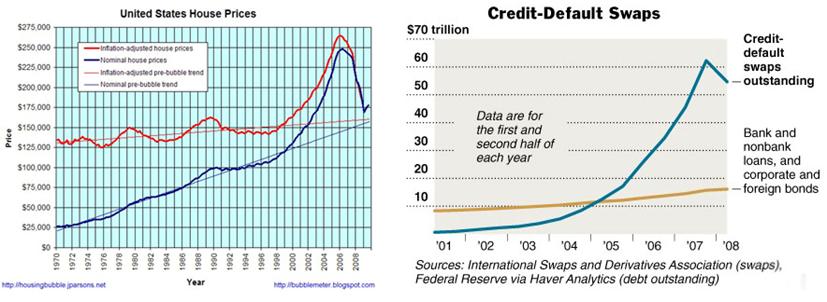

This would be of little import if the CDS market were a trivial part of the financial system, but in a world where this market grew from $631 billion in 2001 to over $62 trillion in just six years this market is far from a trivial part of the financial system. (ISDA) What's more, if the financial markets were efficient in 2001 they most certainly could not have remained so by 2007 as the CDS market's growth exploded over the intervening years. It is inconceivable that pumping $62 trillion worth of default insurance into the financial system would not have had an effect on prices by increasing the demand for the assets that were insured thereby increasing their prices and lowering their corresponding returns. At the same time one would expect investors to be less willing to hold Treasury securities thereby decreasing their prices and increasing their returns.

These returns are represented by r and rt in equation (1) above, and it is clear from this equation the fall in r and increase in rt would, in turn, lower the Treasury spread, rts. This, in turn, would require a reduction in the spread on CDSs (rcds) to keep this market expanding. At this point the Treasury spread (rts) would have no relation to the default risk associated with the underlying assets but, rather, would be determined by the spread at which CDS sellers were willing to insure the underlying securities (rcds). If markets were efficient in 2000 they most certainly would not have been by 2007 since all of this would have occurred in a situation where the estimates of sellers in the CDS market who provided the insurance that drove rt up and rcds and rts down were biased toward underestimating default risk.

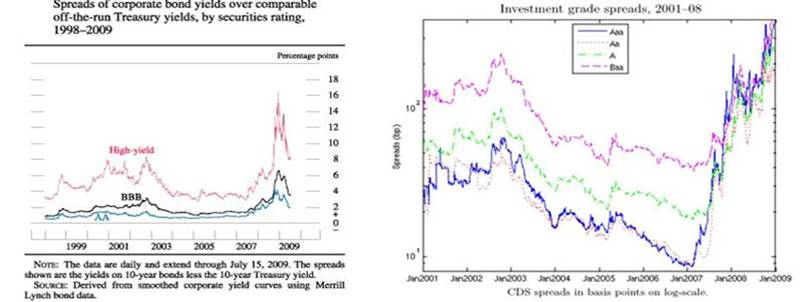

That the data at least appear to be consistent with the above description of the CDS market is indicated by Figure 1 which contains two charts prepared at the Federal Reserve (Fed Gordy) that seem to show a downward trend in corporate bond-Treasury and CDS spreads as the CDS market exploded from 2002 through 2007.

Figure 1

If the above analysis of the CDS market is correct, can there be any wonder that explosive growth in a market whose primary economic justification is to provide a mechanism for speculators to bet the market overestimates risk should be a precursor to the kind of economic catastrophe that resulted from the housing bubble which, coincidently, grew and collapsed in unison with the growth in the CDS market? (See Figure 2 from RiskAndReturn.net and NYT)

Figure 2

There may, of course, be reasons other than to speculate against the market that would lead rational buyers to purchase CDSs at spreads equal to or greater than their corresponding Treasury spreads or sellers to sell CDSs at spreads below the corresponding Treasury spreads even when they estimate the risk to be higher. Regulatory and financial arbitrage come to mind whereby CDSs are used to avoid government regulation or to generate misleading financial statements in such a way as to benefit the arbitrageur. Perhaps CDSs can be used as part of complex speculative hedging strategies in a way that justifies otherwise irrational behavior on the part of buyers and sellers, but these uses hardly justify a market that disrupts market efficiency, nor do they provide a justification for not regulating this market.

This is particularly so in view of the fact that insurance is, by its very nature, a controlled Ponzi scheme whereby the premiums paid in by the policy holders are paid out to the policy holders to cover their losses. The potential for abuse in this kind of endeavor is enormous, especially when the market is expanding as the antics of AIG bear witness. Not only should the CDS market be regulated, regulators should take a very close look at the reasons buyers and sellers participate in this market. There would seem to be no economic justification for allowing this market to even exist, let alone to allow it to dominate the estimation of default risk in the financial system.

Endnotes

[1] The spread of a CDS is the rate of return paid to the seller on the principal of the underlying security insured against default risk by the CDS. If the spread of the CDS is 2% the seller receives a premium equal to a two percent return on the principle of the underlying security. This means that if the interest rate on the underlying security is 6% and the purchaser of the CDS pays a spread of 2% to insure against the risk of default, the purchaser receives a net return of only 4% from holding the underlying security after it is insured.

[2] It can be argued that rt includes liquidity or other kinds premiums as well as default risk. I am ignoring these premiums here as they do not invalidate the argument. Their existence would reduce the magnitude of the bias but not eliminate it.