On International Finance and Trade

Last updated 7/27/2011

Following the economic recovery of Europe from the devastation of World War II, the American dollar became overvalued in the international exchange markets in the late 1950s. (Appendix) This problem came to a head in 1973 when the Nixon administration allowed the fixed exchange rate system with its provisions for controlling international capital flows set up by the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement to collapse. International exchange rates have floated in unregulated markets ever since, and, as a result, the international exchange system has become the largest gambling casino in the history of man. Financial institutions place trillions of dollars of bets in this casino on a daily basis as they manipulate international capital flows throughout the world. Insiders who gambled in this market can made huge amounts of money, but when things go wrong, the results are catastrophic. (Mavroudeas EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik Graeber)

International Crises and Financial Bailouts

There have been four occasions since 1974 where the United States government has had to step in to bail out American financial institutions that bet wrong in this casino: The first was in the early 1980s during the Latin American Debt Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Latin American countries. The second was in 1994 during the Mexican Peso Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Mexico. The third was in 1998 when an American hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management, over extended itself throughout the entire world during the Asian Currency Crisis that precipitated the Russian Default. The fourth was in 2008 when the world financial system ground to a halt in the wake of the Subprime Mortgage Crisis caused by American financial institutions marketing fraudulent mortgage backed securities all over the world.

All of these crises led to economic catastrophes—for the Latin American countries in the 1980s, for Mexico following the Peso Crisis in 1994, for Russia and the South and East Asian countries following the 1998 Asian Currency Crisis, and for most of the world following the worldwide financial crisis of 2008. At the same time, these crises were preceded by huge paper profits for the institutions that fostered the speculative bubbles that led to these crises as well as huge salaries and bonuses for the managers of these institutions. Those who were able to take advantage of these catastrophes made fortunes while most everyone else was left holding the bag. This is especially so for those who rely on wages and salaries for their livelihood, who are forced to live with the uncertainty and economic losses caused by these catastrophes, and whose taxes must pay for the economic bailouts that result. (Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

In addition to creating a cycle of international crises and bailouts, the officials in charge of our government have allowed the American dollar to be overvalued in international markets for much of the past thirty years. This act of misfeasance, malfeasance, or just plain incompetence has been so devastating to our economic system that it will take decades, if not generations, to repair the damage, if it is not too late already. (Phillips Eichengreen)

The Overvalued Dollar and Trade

In theory, the interaction of supply and demand in the markets for international exchange is supposed to yield an optimal allocation of international investment, production, and consumption. But this theory ignores the casino like nature of the foreign exchange markets and the ability of a country to undervalue its currency in world markets if left unchallenged to do so. (Appendix) In the real world, a persistent deficit in the balance of trade is far from ideal, and can have devastating consequences.

When the dollar is overvalued it causes domestic wages and prices to be too high relative to foreign wages and prices to achieve a balance in trade. The result is an increasing deficit in our balance of trade as imports grow more rapidly than exports. (Appendix) This kind of trade imbalance places pressure on wages and prices in the domestic economy as the under pricing of foreign labor and goods threatens domestic producers with unfair competition from abroad. (Autor Appendix)

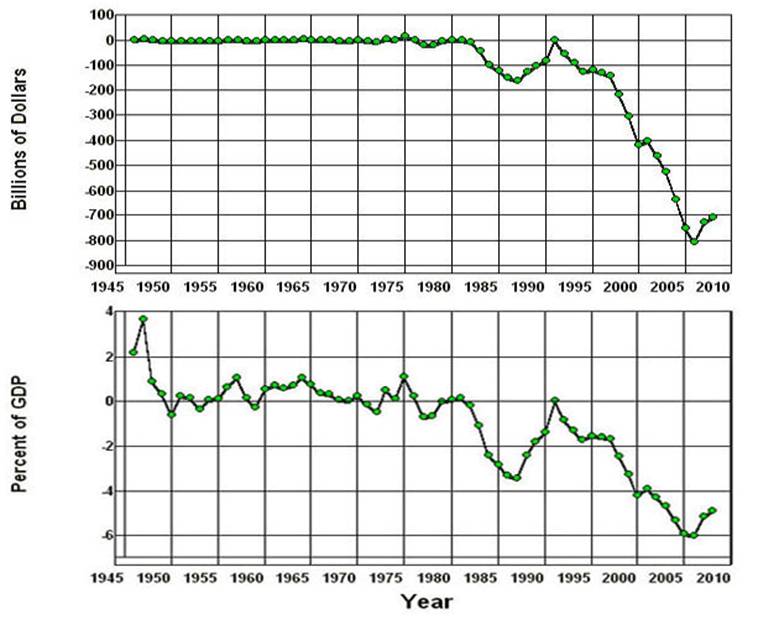

The extent to which our trade policies have allowed this to happen is indicated in Figure 1, which show our current account balance in international trade from 1946 through 2008, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP. The current account balance is determined primarily by the difference between the value of our exports and the value of our imports and provides a general measure of our balance of trade by looking at the funds generated by, and needed to finance international trade.

Figure 1: US Current Account Balance 1946-2008.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2010 (B103PDF-XLS B1PDF-XLS).

The graphs in these figures clearly show the consequences of our international policies as we went from a relatively stable balance through 1980 to a $160 billion deficit in 1987 that amounted to 3.4% of GDP. This balance gradually adjusted through 1991 then fell precipitously to reach a record deficit of $804 billion in 2006, a deficit equal to 6.0% of GDP.

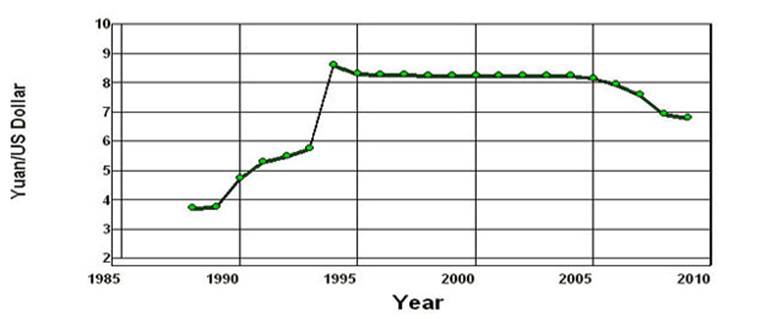

International exchange rates are supposed to adjust to eliminate this kind of imbalance, as they did in the 1980s, but, as was noted above, this will occur only if a country is not allowed to undervalue its currency in world markets over time. Figure 2 shows the Chinese yuan/dollar exchange rate from 1988 through 2009. Here is a classic example of how unregulated international exchange markets can fail to adjust as they are supposed to. Even though the trade deficit with China grew from $68.8 billion in 1999 to $372.7 billion through 2005, there was virtually no change in the yuan/dollar exchange rate from 1995 through 2005. (Appendix)

Figure 2: Chinese Yuan/US Dollar Exchange Rate, 1988-2009.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2010 (B110PDF-XLS).

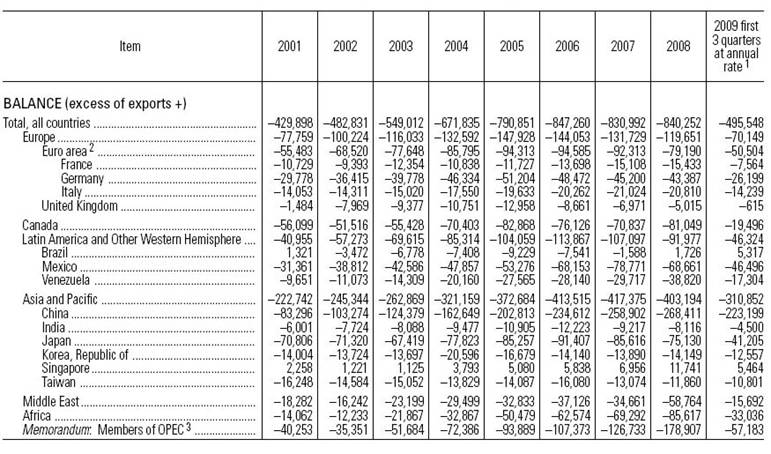

It is worth emphasizing at this point that even though our trade deficit with China is three times that of our deficit with all of Europe or Latin America or the rest of Asia, the problem is not just with the yuan/dollar exchange rate. As should be clear from Figure 3, the entire structure of US exchange rates is overvalued today. The table in this figure shows the US balance of trade with its major trading partners and with the major trading areas of the world from 2001 through the third quarter of 2009. A clear indication of the degree to which the entire structure of US exchange rates is too high is given by the fact that the only entity in this table with which the United States has had a consistent positive balance over this nine years is Singapore. Undoubtedly, some of the deficit exhibited in this table can be explained by the growing need for international reserves, but certainly not all.

Figure 3: US International Trade Balance by Area,

2001-2009. (Billions of Dollars)Source: Economic Report of the President, 2010 (B105PDF-XLS).

This situation is unsustainable, and the exchange markets will adjust to correct this imbalance, but the point is that when this kind of imbalance is allowed to persist for any length of time, the eventual adjustment has the potential to precipitate a crisis that can lead to an economic disaster—a disaster that could have been avoided had this kind of imbalance not been allowed to occur in the first place. (Stiglitz Galbraith Reinhart Eichengreen Rodrik) In addition, the persistence of this kind of imbalance has terribly destructive effects on the domestic economy.

The result of the unfair competition created by the overvalued US dollar has been the destruction of entire industries in the United States as the manufacture of high value, low weight items has been outsourced to foreign lands. Particularly hard hit in this regard are the computer and consumer electronics industries. Equally disturbing is the fact that the technologies necessary to produce these goods have been shipped abroad as well. These technologies are essential to the increases in productivity necessary to improving our economic well being, but once the industries that embody these technologies are gone, they are gone for a very long time. Even if the value of the dollar were to fall in the near future, it would take years to reconstitute many of these industries and to embed in the American economy the requisite capital and technologies needed to produce these goods. (Phillips Eichengreen Rodrik)

The Overvalued Dollar and International Debt

The trade deficits cause by an overvalued dollar have another disturbing consequence. When we have a deficit in our balance of trade, the demand for dollars in the exchange markets to finance our exports is less than the supply of dollars made available in these markets through the purchase of our imports. This difference shows up as a deficit in our current account. When such a deficit exists, foreigners end up accumulating more dollars than they need to purchase the amount of our exports they are willing to purchase at existing exchange rates. (Appendix)

At this point, foreigners have a choice: They can either refuse to accept more dollars at the existing exchange rates and, thereby, force our exchange rates down—thus, stimulating our exports and inhibiting our imports until a balance is obtained at a lower exchange rate—or they can use the excess dollars they are accumulating to purchase assets from Americans in the international capital markets. The assets purchased are essentially any asset an American is willing to sell but primarily consist of financial assets such as government and corporate securities.

The balance in the international capital market is referred to as our capital account balance, and this balance must, by definition, exactly offset our current account balance—that is, a deficit in our current account must be offset by a surplus in our capital account that is exactly equal to the deficit in our current account. (Ott B103PDF-XLS)

When foreigners buy American assets in the international capital market, they are, in effect, investing in the United States. At the same time, to the extent these assets are government and corporate bonds, they are lending us money. This means that the greater our current account deficit, the grater our capital account surplus must be, and, as a result, the current account deficits displayed in Figure 1 above indicate the rate at which we were driving ourselves deeper and deeper into debt to foreigners.

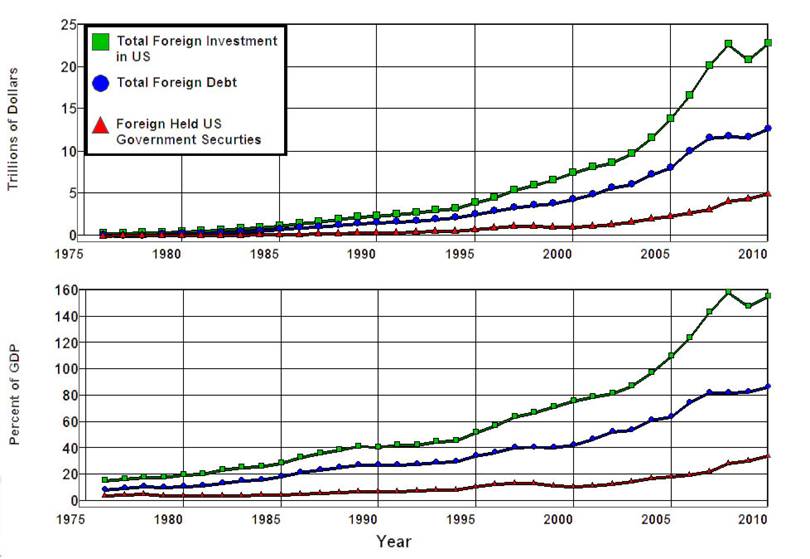

Figure 4: Foreign Investment in US, 1976-2009.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2010 (B1PDF-XLS) and Bureau of Economic Analysis (XLS).

Figure 4 show the extent of foreign investment in the United States from 1976 through June 2009, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP. They show how the surpluses in our capital account that correspond to the deficits in our current account have added to our foreign debt since 1975:

|

The top line in these two figures shows the total value of American assets owned by foreigners. | |

|

The middle line shows the total value of these assets that consist of either corporate or government debt instruments. | |

|

The bottom line shows the total value of these assets that consist of United States Government debt obligations. | |

|

The difference between the middle and bottom line consists of private and municipal debt obligations held by foreigners. | |

|

The difference between the middle and top line consists of direct investments in the United States by foreigners (real estate, factories, businesses) and to a lesser extent equity in American corporations. |

It is clear from this figure that there has been a fundamental change in our indebtedness to foreigners as a result of our free trade policies. Since 1976, our debt to foreigners has increased from a mere $198 billion (11% of our GDP) to $12.7 trillion by 2010 (87% of our GDP), and foreign ownership of our federal debt has gone from $120 billion (6.6% of GDP) to $5.0 trillion (35% of GDP). (BEAXLS B1PDF-XLS)

These investments in American securities by foreigners are, of course, partially offset by investments in foreign securities by Americans. What is disturbing about this situation, however, is that because of the size of our current account deficits, these investments are only partially offset by investments in foreign securities by Americans. At the end of World War II the United States was the largest creditor nation in the world, but as a result of the over valuation of the dollar, this ended in 1985 when we became a net debtor to the rest of the world. As a result of our trade policies we have increased our net debt to foreigners by some $2.7 trillion since 1984, and, in the process, we have gone from being the world's largest creditor nation to the world's largest debtor nation. (BEAXLS IMF)

Why Foreign Debt Matters

For a country to accumulate foreign debt as it runs a persistent trade deficit is not, in itself, a bad thing. The United States followed this course throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, but throughout that period we imported capital goods and foreign technology. We invested in public education and infrastructure that led to tremendous increases in productivity in agriculture and manufacturing. We built national railroad and telegraph systems and created steel, oil, gas, electrical power, automobile, and aviation industries. Our trade policies protected our manufacturing industries as our economy grew more rapidly than our foreign debt, and as Europe squandered its resources in senseless conflicts, by the end of World War I the United States was a net creditor nation and the economic powerhouse of the world.

This is not the situation we find ourselves in today. Today we are exporting rather than importing capital goods and technology, and, in return, we are borrowing to import consumer goods. We are investing less in our public education, transportation, and other public infrastructure systems, rather than more. While we have made huge advances in the electronics and computer industries over the last forty years, our trade policies are not protecting our manufacturing industries, and we have outsourced the manufacturing and technological components of these industries to foreign lands. As a result, our economy is not growing more rapidly than our foreign debt, and it is the United States that is squandering its resources in senseless conflicts.

This process of rising trade deficits can sustain itself only so long as foreigners are willing to lend us the money to pay for these deficits. When foreigners refuse to continue to do so—as eventually they must if our foreign debt continues to rise faster than our GDP—the existence of this debt makes us vulnerable to the same kinds of crises faced by Iceland, Greece, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe today. (Stiglitz Galbraith Reinhart Kindleberger Philips Morris Klein Eichengreen)

Appendix on International Exchange

Exchange Rates and International Trade

To say the American dollar is overvalued means that our foreign exchange rates are too high, where exchange rates are nothing more than the prices foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars. If the Chinese must pay 10 yuan to purchase one dollar, the YUAN/USD exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar. Similarly, if the EURO/USD exchange rate is 1.5 euros per dollar, Europeans must pay 1.5 euros to purchase one dollar. The higher the exchange rate, the greater the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars. The lower the exchange rate, the lower the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars.

Of course, this works in reverse when it comes to us buying foreign currencies. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar then we can purchase 10y for one dollar, which works out to a price of 10 cents per yuan. If the exchange rate is 5 yuan per dollar, we can only purchase 5y for one dollar, which works out to a price of 20 cents per yuan. The higher the exchange rate, the lower the price we have to pay in our currency for a foreign currency. The lower the exchange rate the higher the price we have to pay in our currency for a foreign currency.

Exchange rates are extremely important in determining the flow of international trade because for us to purchase goods from a foreign country we must pay for those goods in the currency of that country. Similarly, for foreigners to purchase goods from us they must pay us in our currency. As a result, the exchange rate between two countries' currencies determines the costs of imports and exports between those countries.

To see how this works, consider a bushel of wheat in the United States that costs $3.00. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar, someone in China who wished to purchase this bushel has to come up with 30y to purchase the $3.00 necessary to pay the American farmer in dollars. If, instead, the exchange rate is 5 yuan per dollar, the Chinese purchaser has to come up with only 15y. Given the price of wheat in the United States, the price the Chinese purchaser must pay in yuan for American wheat depends on the exchange rate—the higher the exchange rate, the higher the price the Chinese must pay, and the lower the exchange rate the lower the price the Chinese must pay.

Again, the process works in reverse when it comes to us buying from China. If the price of a bushel of wheat in China is 20y, and the exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar, we have to come up with $2.00 to purchase the 20y in order to pay the Chinese farmer in yuan since each of our dollars is worth 20y. But if the exchange rate is 5 yuan per dollar we have to come up with $4.00 to purchase this 20y. Given the price of wheat in China, the price we must pay in dollars for Chinese wheat depends on the exchange rate—the higher the exchange rate, the lower the price we must pay, and the lower the exchange rate the higher the price we must pay.

The importance of exchange rates in determining the costs of imports and exports between countries should be clear from this example. If the exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar it is not cost effective for the Chinese to purchase our wheat since it costs them 30y to purchase the $3 needed to buy a bushel of American wheat, and it only costs them 20y to purchase a bushel of Chinese wheat. But if the exchange rate is 5 yuan per dollar, it is cost effective for the Chinese to purchase our wheat since it then costs them only 15y to purchase the $3 needed to buy a bushel of American wheat and their wheat costs 20y. This is assuming, of course, that it costs less than 5y per bushel to transport wheat from the United States to China.

Similarly, if the exchange rate is 5 yuan per dollar it is not cost effective for us to buy Chinese wheat since we have to pay $4.00 to purchase the 20y needed to pay for a bushel of Chinese wheat, and it only costs $3.00 to purchase a bushel of American wheat. But if the exchange rate is 10 yuan per dollar it only costs $2.00 to purchase the 20y needed to buy a bushel of Chinese wheat, and we can save $1.00 per bushel by buying Chinese wheat instead of our own.

It is important to note that wages are nothing more than the prices of labor, and the exchange rate determines the relative wages between countries in the same way it determines any other relative price. An increase in the exchange rate makes foreign wages less relative to our wages. A fall in the exchange rate makes foreign wages higher relative to our wages. Thus, an overvalued currency in the international exchange markets places severe pressure on wages in the domestic economy since it makes our wages higher relative to foreign wages than they would be if our currency was not overvalued.

International Capital Flows

When the value of a country's imports is equal to the value of its exports it can obtain enough foreign exchange to finance its imports from the sale of its exports. If it has a deficit in its balance of trade, however, it can only finance its imports, at the current exchange rate, if it is able to obtain the difference in the international capital market which is the market through which foreign investments are made. This is where international capital flows come in. A country can only have a deficit in its balance of trade if foreigners are willing to invest in that country—either directly by purchasing real assets in the country or indirectly by purchasing financial obligations (stocks, bonds, money, etc.) of the country—thereby providing the foreign exchange needed to make up the difference. If foreigners are not willing to make this investment, the country's exchange rate must fall causing the costs of its imports to rise as the costs of its exports fall until a balance is achieved.

The problem is that while imports and exports of goods and services change relatively slowly over time, the purchase and sale of the financial assets that make up international capital flows can take place almost instantaneously. This can cause serious instability in international exchange rates and precipitate international financial panics and crises. Under The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) that was part of the Bretton Woods Agreement, provisions were made for countries to control foreign investments in order to prevent these kinds of disruptions in the international markets for their currency. These provisions were rejected in the Washington Consensus that came to dominate American foreign policy following the 1973 collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement.

When the value of a country's imports exceeds that of its exports, the country has a deficit in its balance of trade. In this situation, the demand for the country's currency in the international exchange markets to finance its imports is less than the supply from the sale of its exports, and, in the absence of foreign investment, this must lead to its exchange rates being bid down. The decrease in its exchange rates, in turn, will cause the domestic costs of its imports to increase and the costs of its exports to foreigners to decrease, which, in turn, should cause its imports to fall and exports to increase until a balance a achieved. (Strictly speaking, it is the country’s current account, which includes net income on foreign investments as well as exports and imports, that should adjust in this way. To simplify the discussion I use the terms current account and balance of trade interchangeably without distinguishing between them.) This process works in reverse when a country has a surplus in its balance of trade. In fact, it is the same process since a given country's surplus is some other country's deficit, and the imports on one country are the exports of another.

If a country, such as China, is willing to make this investment it can accumulate U.S. assets and prevent our exchange rate with that country from falling. There are advantages to a country that does this. It can earn an income on the assets it accumulates, and it keeps its own exchange rate with us from increasing (our exchange rate with them from falling). This makes it possible for the country to keep our demand for its exports from falling and, thus, stimulates its economy. There is also a risk in their doing this. Since the assets they accumulate are denominated in dollars, they will take a capital loss on these assets when their exchange rate eventually rises (our rate falls) since these assets will then be worth less in terms of their own currency.

As is apparent from Figure 3, almost all countries have been willing to take this risk in recent years in order to build up their international reserves and stimulate their economies. As is explained in the text, when this situation persists for any length of time it can have very negative effects on our economic system. (Galbraith Eichengreen Autor)