Why Democrats Lose Elections

George H. Blackford (Last updated: 05/25/2015)

Here lies the body of Jonathan Gray

Who died maintaining the right of way

He was oh so right as he sped along

But he's just as dead as if he were wrong

(Unknown)

Index

The Republicans' Budget Cutting Fantasy

The Republicans' "We Are Terribly Overtaxed!" Delusion

The Democrats' Record Since 2009

A Political Lesson from the 1930s

A Political and Economic Strategy that Could Work

Appendix on Deficit Spending

EndnotesIn a recent survey (February 2013), the

Pew Research Center asked 1,504 respondents: "If you were making up the budget for the federal government this year, would you increase spending, decrease spending or keep spending the same" for nineteen different categories of government expenditures. For all but three categories of expenditures—Aid to the world's needy, State Department, and Unemployment aid—a larger proportion of the respondents would increase rather than decrease expenditures, and for all categories, even those three, a majority of those who had an opinion said they would either increase expenditures or keep them the same.These results are fully consistent with the Gallup surveys on the Federal Budget Deficit

since 2011, and they strongly suggest that the vast majority of the American people is satisfied with the size of the federal government or, if anything, would like to see it increased rather than decreased. This is especially so in view of the fact that the three categories in which more respondents would rather decrease than increase add to less than 3% of the federal budget while just five of the categories which more respondents would increase rather than decrease—Social Security, Military defense, Medicare, Health care, and Aid to needy in U.S.—make up over 70% of the federal budget.The Republicans' Budget Cutting Fantasy

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) publishes an annual report that provides long-run projections of the federal budget under two scenarios: an extended baseline scenario, which is based on current law, and an extended alternative fiscal scenario, which is based on past and current practices. For the past ten years these reports have made clear the actual choices the American people must face with regard to federal taxes, debt, and government services to the effect that we must either:

1. increase federal taxes substantially (by as much as 14.6% according to the 2014 report),

2. decrease federal expenditures substantially (by as much as 13% according to the 2014 report), or

3. allow the federal debt to increase continually relative to income.

[1]The following chart shows a breakdown of federal expenditures in 2014 with the CBO's 13% hole in it:

Figure 5: United States Federal Budget, 2014.

Source: Office of Management and Budget (3.2 11.3)

(Click Here For 2019 Federal Expenditures)

What does this chart tell us about the Republican insistence that they can maintain the government the vast majority of the American people want and, at the same time, solve our long-run deficit problem without increasing taxes?

Even a casual examination of this chart reveals that it is impossible to maintain the government the vast majority of the American people want and, at the same time, reduce government expenditures by as much as 13% through spending cuts:

![]() Maintaining our current levels of

expenditures on Social Security and Medicare—as over 80% of the respondents

in the Pew poll say they would chose to do—leaves only 55% of the budget to

cut after deducting the 6% of the budget that goes to interest on the

national debt. It would require a 24% cut in the rest of the budget to cut

the total budget by 13% if we were to exempt Social Security and Medicare

from cuts.

Maintaining our current levels of

expenditures on Social Security and Medicare—as over 80% of the respondents

in the Pew poll say they would chose to do—leaves only 55% of the budget to

cut after deducting the 6% of the budget that goes to interest on the

national debt. It would require a 24% cut in the rest of the budget to cut

the total budget by 13% if we were to exempt Social Security and Medicare

from cuts.

![]() Maintaining

our current levels of expenditures on aid to the needy in addition to those

on Social Security and Medicare—as over 80% of the respondents in the Pew

poll also say they would chose to do—leaves only 38% of the budget to cut

after deducting interest on the national debt. A 13% cut in the total budget

would require a 34% cut in this 38% of the budget.

Maintaining

our current levels of expenditures on aid to the needy in addition to those

on Social Security and Medicare—as over 80% of the respondents in the Pew

poll also say they would chose to do—leaves only 38% of the budget to cut

after deducting interest on the national debt. A 13% cut in the total budget

would require a 34% cut in this 38% of the budget.

![]() And

if we were to include maintaining our current levels of defense among the

excluded categories—as over 70% of the respondents in the Pew poll say they

would chose to do—it would leave only 21% of the budget to cut. A 13% cut in

the total budget would require a 60% cut in this 21% of the budget.

And

if we were to include maintaining our current levels of defense among the

excluded categories—as over 70% of the respondents in the Pew poll say they

would chose to do—it would leave only 21% of the budget to cut. A 13% cut in

the total budget would require a 60% cut in this 21% of the budget.

Where are these cuts supposed to come from? From eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse? I don't think so! As I have explained in Waste, Fraud, and Abuse in the Federal Budget, the idea that we can reduce the federal budget 16% by eliminating waste, fraud, and abuse only makes sense to those who refused to look at the numbers or are illnumerate, (See Understanding The Federal Budget for a comprehensive explanation of the budget.)

The Republicans' "We Are Terribly Overtaxed!" Delusion

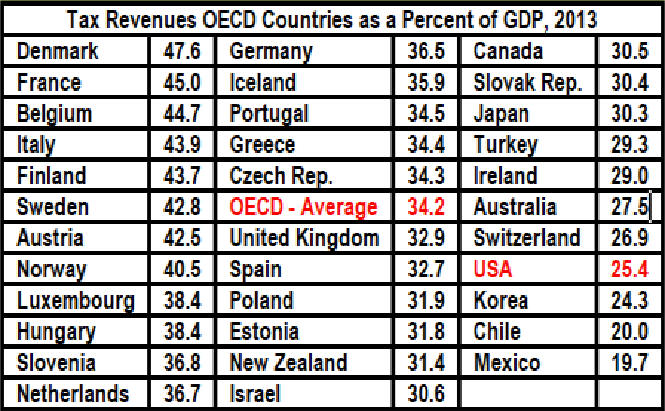

The fact that Americans are not terribly overtaxed is shown quite clearly in the following tables which are constructed from the official statistics of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). These tables show how the ranking of the United States among the OECD countries for which data is available has changed since 1980 in terms of total government tax revenues as a percent of gross income (GDP) as well as this percentage for all OECD countries in 2012.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, (Comparative Tables

The United States ranked forth from the bottom on this list in 2013. We collected 26% less in taxes in that year than the average for the OECD countries (34%), 38% less than the 15 countries that were above the average (40%), 41% less than the top 10 countries (43%), and these are the most prosperous and economically advanced and productive countries in the world!

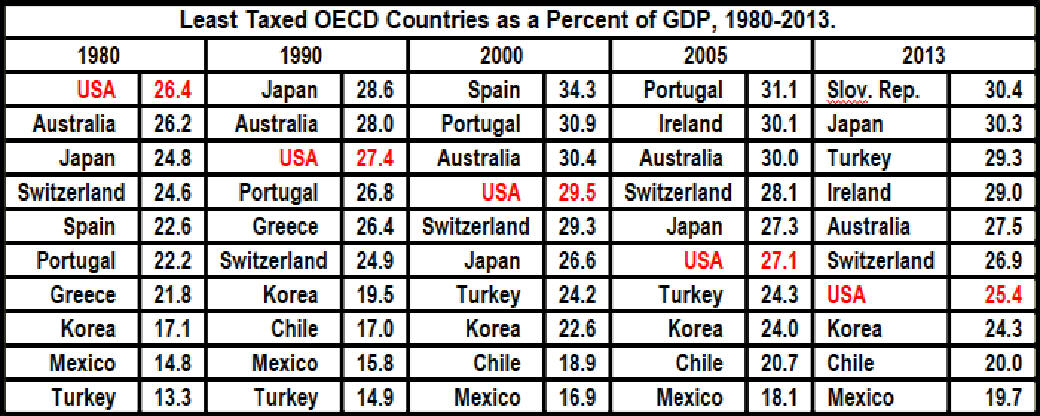

When we look at the financing of the federal government we find that federal tax receipts equaled 18.2% of GDP in 2014, 21.1% of National Income, and 21.5% of Personal Income.[2] If we were to add the 14.6% increase in taxes that would be required to fill the 13% hole the CBO projects the federal government will need fill in order to stabilize the federal debt in the future, it would increase the total to 20.9% of GDP, somewhat above the 19.1% of GDP collected in 2000.[3] That would amount to a tax increase equal to only 2.7% of GDP and 3.1% of National and Personal Income:

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (3.2)

This would seem to be a rather small price to pay to fill the CBO's 13% hole in the federal budget in order to avoid the kinds of drastic cuts in federal programs and services indicated above, and to preserve Social Security, Medicare, national defense, our physical infrastructure, and all of the other federal programs and services the American people care about.It is a simple fact that a modern economic system cannot prosper in the absence of a major portion of its economic resources being devoted to the production of government services: quality public education that provides an educated and productive work force; effective public health programs that prevent epidemics of disease; fair and just legal, criminal justice, and law enforcement systems that provide for the rule of law and safe streets and neighborhoods; regulatory systems that protect the environment, ensure effective and efficient communications, transportation, power distribution, and stable economic growth and that also provide for safe foods, drugs, consumer products, and working conditions; a comprehensive system of streets, roads, highways, ports, and other forms of public transportation that facilitate the efficient movement of goods and people; an effective national defense to protect the nation's sovereignty and the physical security of its people; and a viable social insurance system that provides its citizens protection against the possibility of a devastating loss that results from the vagaries of life.

These essential government programs and services cannot be provided in a fair or just or efficient or effective manner by private enterprise guided by the profit motive. They can only be provided in this manner by a democratically elected government whose elected officials are dedicated to achieving these ends. And they most definitely cannot be provided in this manner by elected officials whose sole objective is to cut taxes and, thereby, defund the government programs that are designed to provide these essential government services and benefits. What's more, they must be paid for, and the Republican argument to the effect that we can't afford to pay the taxes needed to pay for these essential government programs and services is just as absurd as their notion that we can have all of government programs and services that are essential to our economic prosperity and social wellbeing by cutting government expenditures to balance the budget instead of raising the taxes needed to pay for them.

The Democrats' Record Since 2009

One would think that given the reality of what the American people want and what the Republicans have to offer Democrats would have little difficulty in brushing the Republicans aside come election time. Unfortunately, this has not been the case.

After the Democrats took control of the White House in 2009, along with a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate, the deficit increased from $459 billion in 2008 to $1.4 trillion in 2009 as federal debt went from 43% of GDP to 54% of GDP. In response, the Republicans cried we're going to go broke if we don't cut taxes on job creators and reduce wasteful government spending to which the Democrats' economic advisors on the left responded that deficits and debt aren't what's important. What's important is unemployment, and to reduce unemployment we have to increase the deficit.

And so it went through 2010 as the national debt grew from 54% to 63% of GDP, the economy failed to recover, and the Democrats lost control of the House and their filibuster-proof majority in the Senate as the Republicans continued to beat the Democrats over the head with the deficit and debt and the need to cut taxes and government spending, and the Democrats continued to try to explain why the Republican proposals didn't make sense and that we don't have to worry about the debt.

Then came the Debt Ceiling Crisis and Sequestration as the Democrats barely managed to squeak through the 2012 election in spite of Romney's self-destructive 47% gaff as the debt reached 71% of GDP. Next came the grand Bipartisan Budget Deal, and throughout it all the debate was about the national debt with the Republicans insisting that the debt must be managed and the Democrats, following the advice of their political advisors, compromising on this issue at every turn while their economic advisors argued that the debt doesn't matter right through the 2014 election as the debt rose to 74% of GDP, and the Democrats lost control of both the House and the Senate.

Now, as we head into the 2016 election and the Republicans are poised to take over the White House as well as Congress, the Democrats' economic advisors on the left are still trying to convince the world that deficit spending is good for the economy during a depression and we don't have to worry about deficits and debt.

This record is very different from that of the Democrats in the 1930s who were faced with an economic crisis similar to the one we are faced today. The Democrats won a slight majority in the

House in 1930 and took over the Senate along with the White House in 1932. They then increased their majorities in the House and Senate in the following two elections, in spite or the rising deficit and debt, and retained the presidency in 1936. Then came the economic disaster following 1937 when the Democrats foolishly tried to balance the budget by cutting expenditures as the Federal Reserve raised reserve requirements which caused unemployment to increase by five percentage points in 1938, and, yet, even though the Democrats lost 72 seats in the House and 7 seats in the Senate in the 1938 election, they maintained substantial majorities in both the House (262D, 169R) and the Senate (68D, 23R) in 1938. And in spite of the recession in 1938, the Democrats increased their majority in the House by five seats and lost only three seats in the Senate in 1940 as Roosevelt won his unprecedented third term. This difference should at least suggest to the Democrats today that, even though they think they have the economics of the current crisis right, there is something wrong with their politics in the way they have managed the current economic crisis.A Political Lesson from the 1930s

One of the most striking differences between the Democrats of the 1930s and the Democrats today is that the Democrats of the 1930s did not try to explain to the American people that deficit spending is good for the economy or that the debt doesn't matter. Not only did they campaign vigorously against allowing the deficits and debt to get out of control,

Democrats increased taxes in every year from 1932 through 1936. The political lesson to be learned from this, in contrast to the election results since 2008, is that trying to convince people that they don't have to worry about deficits and the national debt is a fool's errand.A standard question in the annual Gallup surveys on the Federal Budget Deficit is "How much do you personally worry about federal spending and the budget deficit?" From 2011 through 2014 the answer to this question has indicated that over 80% of the population worry either a "Great deal" or a "Fair amount" about this issue with around 60% or the respondents indicating that they worry about this a Great deal. Similar results have been reported by the Pew Research Center and, in fact, this sort of attitude toward deficits and the National Debt has played a major role in American politics since the 1930s and, undoubtedly, even before then.

The reason a majority of the public feel this way is that there are three things about deficits and the national debt that virtually everyone knows:

1. Government programs and services must be paid for.

2. We pay for government programs and services by collecting taxes and borrowing and printing money.

3. If the government tries to fund its programs and services by continually borrowing and printing money instead of by collecting the taxes needed to stabilize the national debt relative to income it will eventually lead to an economic catastrophe.

Even those who are trying to convince the American people that deficits and the national debt don't matter do not deny these realities.

Given these realities, what does it mean when those on the left try to explain to the American people that we have to increase the deficit to get the economy going while those on the right argue that we have to balance the budget by cutting taxes on job creators and eliminating government waste to achieve the same end? What is the choice this debate offers the electorate, and in particular, the nonideological voters who comprise the majority of the electorate and who neither understand nor care about the nuances of macroeconomic policy?

Since both sides are arguing that they are trying to achieve full employment and economic growth, the choice comes down to increasing the national debt or cutting taxes on job creators and eliminating government waste. Is it really surprising that only 36.3% of the eligible voters bothered to vote in the last election—the lowest turnout in over seventy years—when they were faced with this choice? How many people care passionately about increasing the national debt or cutting taxes on job creators and eliminating government waste? And of those who do feel passionately about either of these two issues, how many feel passionately about the need to increase national debt as compared to those who feel passionately about cutting taxes on job creators and eliminating government waste?

It’s not difficult to understand why Democrats lose elections when they offer this kind of choice to the electorate. After all, no one feels good about increasing the national debt, and hardly anyone feels passionate about doing this, while almost everyone thinks cutting taxes and eliminating government waste is a good idea, even if they aren't rich, and quite a few people feel passionate about this, especially if they are in the top 10% of the income distribution.

What's even more important in understanding why Democrats lose elections, however, is the realization that there are virtually no Democrats in office or running for office today who are willing to take a stand and fight for the kinds of things that the American people actually do care about. This is the fundamental difference between Democrats today and those of the 1930s. The Democrats in the 1930s fought for things that people cared about—Social Security, regulating the financial system, putting people to work through the Civilian Conservation Core, National Youth Association and Works Progress Administration as they built dams and roads and electrified rural areas and built up our parks and other public recreational facilities.

In other words, the Democrats of the 1930s stood for something that the people could understand, and instead of trying to explain to the people why debt doesn't matter, the Democrats in the 1930s raised the taxes needed to justify the programs they implemented. Even though the American people were just as worried about the deficits during the 1930s as they are today, they also knew that the Democrats were fighting for the kinds of things that the people cared about and were doing their best to deal with the deficit and debt problem by raising taxes. As a result, they kept voting for the Democrats even after the economic disaster of 1937.

A Political and Economic Strategy that Could Work

In a Pew Research Center/USA Today survey, also conducted in February of 2013, the respondents were asked if the president and Congress should focus on spending cuts, tax increases, or both in order to reduce the federal budget deficit. An overwhelming majority of respondents (73%) indicated they would like to see the federal deficit problem solved through only or mostly spending cuts rather than through only or mostly tax increases (19%).

In other words, it would appear that an overwhelming majority of the American people would like to have their cake and eat it too: they want to increase the size of the federal government or keep it the same as they solve the deficit problem through only or mostly spending cuts. It should not be surprising the American people feel this way when the political debate raging around them is about stimulating the economy either by cutting taxes on job providers and eliminating government waste or increasing deficits and the national debt because, by the very nature of this debate, it has not made clear to the American people the actual choices that are available to them.

If the Democrats are to win elections they have to find a way to distinguish themselves from the Republicans on issues that the American people care about, and this is rather easy to do. As has been indicated above, all the Democrats have to do to find these issues is look at the public opinion surveys and contrast what these surveys tell us about what the American people want with what the Republicans have to offer, and by making clear the actual choices that the American people must face. The place to begin is by looking at what it means when the Republicans demand that we not raise taxes in the face of a 13% hole in the federal budget.

Since a 13% cut in expenditures would have to come out of the noninterest part of the budget it means that the rest of the budget would have to be cut by almost 14% if we are to eliminate the long-run deficit without raising taxes. This obviously cannot be done without making substantial cuts in Social Security (which accounts for 23% of total federal expenditures), Medicare (14%), Medicaid (8%), aid to the needy (11%), and national defense (16%) since this is where the bulk of the money is in the federal budget—over 75% of the noninterest portion of the budget falls into one or the other of these five categories.

In other words, the basic choice facing the American people today is between cutting Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, aid to the needy, and national defense or increasing taxes. This is a choice that people actually care about, and this is what Democrats should be arguing about, not about increasing the deficit and the national debt.

In fact, as the Pew and Gallup surveys discussed above indicate, these are the very government programs and services that the American people care about the most, and if the Democrats want to start winning elections they must make it absolutely clear to the American people that we cannot stabilize the federal debt relative to GDP in the long-run without making substantial cuts in these programs if we do not raise taxes and, in particular, that not raising taxes means substantial cuts in Social Security and Medicare. But the Democrats can only make this clear if their economic advisors on the left get over their obsession with the notion that they have to defend deficit spending, openly acknowledge the fact that the national debt must be stabilized relative to GDP in the long run, and formulate sound economic policies—policies that lead to stable economic growth—that justify the increases in taxes needed to stabilize the debt and finance the government programs and services the American people want.

This can easily be done by arguing in favor of expanding and improving those government programs and services that people actually care about—Social Security, Medicare, education, roads and highways and other physical infrastructure, scientific research, environmental protection, food and drug inspection, law enforcement and public safety, strict regulation of financial institutions and practices, national defense, water and sewage sanitation facilities, aid to the needy, disaster relief, and veterans' benefits—and by arguing that taxes will have to be raised in order to stabilized the debt as these programs and services are to be maintained and increased. If the Democrats were to embrace this sort of argument—an argument that actually makes sense to ordinary people—ordinary people would start to listen to what the Democrats have to say.

And not only is it essential that the Democrats a) stop arguing that we can ignore the deficit and debt, b) start arguing in favor of expanding and improving those government programs and services that people care about, and c) start arguing in favor of raising the taxes that are needed to finance the government programs and services that people care about, it is also essential that Democrats make it absolutely clear who should pay the bulk of the increases in taxes that must be raised in order to stabilize the debt in this situation.

For over forty years we have followed the Republican agenda of deregulating our domestic and international financial systems, cutting taxes on the wealthy and increasing taxes on the not so wealthy, crushing unions, and cutting back on government programs and services that promote the general Welfare and serve the needs of the bulk of the American people to what effect? The result has been an epidemic of fraud that led to the Savings and Loan Crisis and junk bond bubble of the 1980s; the dotcom and telecom bubbles of the 1990s; the Enron, HomeStore/AOL, Global Crossing, WorldCom, and subprime mortgage frauds and the housing bubble in the 2000s—all of which were accompanied by a disastrous increase in our international current account deficit with devastating effects on our domestic manufacturing industries. In the end we are faced with a social and economic catastrophe of epic proportions in which there have been massive transfers of wealth and income from the bottom to the top of the wealth and income distributions as wages have failed to keep pace with productivity, the average earned income of the bottom 90% has fallen below where is was in 1968, and those at the bottom have been forced deeper and deeper into debt as the incomes and wealth of those at the top have soared to astronomical levels.

If we are to dig ourselves out of the economic hole we have dug ourselves into by following the Republican agenda over the past forty years it must be made absolutely clear that those who benefited the most from the epidemic of fraud created by this agenda must pay the bulk of the increase in taxes needed to fund the government programs and services that people care about. This means:

-

rescinding the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (that made the bulk of the 2001-2005 tax cuts permanent),

-

adding additional brackets at the top of the income tax structure,

-

increasing if not eliminating the income caps on Social Security and Medicare taxes,

-

eliminating corporate tax loopholes and increasing corporate income tax rates,

-

dramatically increasing the inheritance tax rates on large estates, and

-

eliminating the special treatment of dividends and of capital gains to the extent that capital gains are not the result of an increase in the general price level and are on assets that have been held for less than five or ten years.[4]

This is an economic strategy that makes sense because, as I have explained in great detail in Where Did All The Money Go?, it focuses the political debate on one of the three central problems that are responsible for the financial crisis that began in 2007 and the economic malaise we are in the midst of today, namely, the concentration of income and wealth within our society, the other two problems being the increase in our current account deficit and the inadequate regulation of the financial system. The problem of inadequate regulation of our financial system can be dealt with through legislation and strict enforcement of existing regulations. Our current account deficit can be reduced through international negotiations and the imposition of sanctions against those who manipulate their exchange rates, and the concentration of income can be reduced by increasing both government expenditures and taxes in ways that are consistent with achieving this end.

This is a political strategy that makes sense because those who oppose expanding and improving the government programs and services that people actually care about—the government programs and services that are essential to our economic prosperity and our social wellbeing—are the same people who feel passionately about not increasing taxes and eliminating government waste, and they most certainly were among the 36.3% of the electorate who showed up to vote in the last election and didn't vote for Democrats. It was those who feel passionately about expanding the government programs and services that people care about and increasing taxes on those who benefited the most from the epidemic of fraud created by the Republican policies we have followed for the past forty years who didn't bother to vote in 2014, and they didn't bother to vote because there was virtually no one running for office in that election who was willing to stand up and fight for the kinds of things the vast majority of the American people care about.

Appendix on Deficit Spending

There was a consensus among mainstream macroeconomists leading up to the current crisis to the effect that monetary rather than fiscal policy should be used to achieve economic stability by way of the Federal Reserve using its powers to keep the market rate of interest at the Wicksellian full-employment (natural) rate of interest. When the crisis came, and the market rate fell to zero, it became apparent that standard monetary policy was not going to be effective in solving our unemployment problem. In response, those on the left turned to New Keynesian models with rational expectations and the traditional Keynesian IS-LM model to suggest alternative policies to deal with this problem.

The New Keynesian models were used to justify "quantitative easing" whereby the Federal Reserve increased the monetary base dramatically in an attempt to lower long-term interest rates and create inflationary expectations with the hope of lowering the real rate of interest to the Wicksellian full-employment rate. On its face, this policy is grasping at a straw since it is very difficult to manipulate expectations, and the dramatic increase in the monetary base is fraught with danger. It has the potential to facilitate the creation of speculative bubbles, the bursting of which can, as we have seen, have devastating effects. In addition, it is not at all clear how the increased monetary base can be managed once full employment is achieved or if inflation or speculative bubbles become a problem.

The traditional Keynesian IS-LM model has been used to justify deficit spending by arguing that when the federal government borrows during an economic downturn in order to maintain or increase expenditures on education, scientific research, public health systems, police and fire protection, water and sanitary treatment facilities, bridges, highways, and other forms of public transportation it increases spending in the economy directly and thereby directly increases the demand for goods and services.

The same argument applies when the government borrows to increase transfer payments or to finance tax cuts that created the need to borrow in order to maintain government expenditures, though here the effect on the demands for goods and services is less certain in that the increases in spending on goods and services are indirect. This kind of borrowing can have an effect on the demands for goods and services only to the extent that those who received the transfer payments or tax cuts increase their spending on newly produced goods and services as a result. There is, of course, no guarantee this will occur, but the increase in borrowing to finance the kinds of transfer payments embodied in food stamps, unemployment compensation, school lunch programs, Medicaid, and other kinds of social welfare programs that tend to increase during an economic downturn help to stimulate the economy since most of these transfers go to people who live hand to mouth, and, therefore, are more or less forced to spend.

In addition, these kinds of expenditures, whether direct expenditures or social welfare transfers, can have the added benefit of making it possible to improve productivity in the future by improving our public infrastructure and warding off the malnutrition and other health problems that are the inevitable consequence of people becoming destitute in the wake of an economic downturn. Thus, even if they have to be financed through borrowing, they add stability to the system and, to the extent they increase productivity in the future, have the potential to help the economy grow and, thereby, help to stabilize the growth of debt relative to income and reduce the burden of servicing the debt the deficits create.

The point to note, however, is that it is the increase in spending on goods and services that results from an increase in government spending or a decrease in taxes that stimulates the economy, not the deficit that requires the government to borrow in order to finance its expenditures. It is also important to note that the deficits that are created in the midst of an economic downturn by giving tax cuts and increasing transfer payments to the ultra wealthy who, in turn, use the proceeds to buy the bonds needed to finance the deficits created by the transfers and tax cuts in the first place do not stimulate the economy and do not have the added benefit of having the potential to improve productivity in the future. They simply increase the transfer burden from taxpayers to bondholders as they distort the allocation of resources within the system without any benefit to the society as a whole. By the same token, increasing the taxes on those who are just sitting on their savings that are not being used to purchase currently produced consumer or investment goods and services, but, instead, are simply being accumulated in bank accounts as excess reserves grow or are used to bid up the prices of safe assets will not have the effect of enhancing economic growth or productivity.

What this means is that an increase in the deficit is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for fiscal policy to stimulate the economy in dealing with our unemployment problem. It is possible for the government to use its tax and expenditure policies to stimulate the economy in a way that minimizes the effect on the deficit by implementing expenditure policies that maximize the amount of spending on goods and services that result from the increase in government expenditures while, at the same time, increasing taxes to fund these expenditures in a way that minimizes the loss in spending on goods and services that result from the increase in taxes. In fact, it means that it is possible to stimulate the economy in this way without increasing the deficit at all.

It also means that there is no relationship between the size of the deficit and the degree of economic stimulus that results from blindly increasing government expenditures and decreasing taxes, and there is no guarantee that the resulting deficits can be eliminated once full employment is achieved, nor is it guaranteed that the deficit that remains once full-employment is achieve will not lead to a situation in which the federal debt will have to increase faster than full-employment income in order to maintain full employment once full employment is achieved and we are no longer at a zero lower bound.

When federal debt increases faster than the GDP it increases the burden of transfers from taxpayers to bondholders which can lead to serious problems, especially if the debt is foreign owned, as it feeds our current account deficit and makes it more difficult to fund government programs. In addition, there is a huge risk of inflation getting out of control once full employment is reached if the federal debt must grow continually relative to GDP in order to maintain full employment, especially when the increase in debt has been combined with quantitative easing, if a point is reached at which the government cannot raise the money needed to service its debt through taxes or borrowing and is forced to print money. The resulting inflation can have the effect of increasing interest rates and, thereby, making the transfer problem worse as it weakens our position in international markets. If severe enough,

hyperinflation can lead to a total collapse of the monetary system as creditors refuse to enter into contracts written in terms of the domestic currency.Thus, at the very least, the federal deficit must be managed in such a way as to stabilize the debt relative to GDP since the failure to do so will increase the transfer burden from taxpayer to bondholders and, in a worst case scenario, can lead to a catastrophe. No matter how unlikely this scenario may seem in the present, it cannot be ruled out a priori in the future. As a result, this possibility should not be ignored, not simply on purely economic grounds, but on political grounds as well. As has been noted above, people, in general, are unwilling to accept the articles of faith needed to blindly ignore this kind of danger and embrace a set of policies that can lead to catastrophe unless they are given a palpable reason to do so such as was the case during World War II.

This means that expenditures by the government that do not involve an investment in the economy designed to increase economic productivity and growth in the future should be financed, as much as possible, through increases in taxes. At the very least, taxes should be increased to the point where we can sustain a government budget that will fund non-investment expenditures through taxes when the economy is at full employment with the full-employment deficit being used to fund only essential public investments that are designed to increase economic growth and productivity.[5] This is a lesson that should have been learned from our experiences in the 1930s, especially when compared with our experience in dealing with the current crisis.

From 1933 through 1937 the deficit averaged 4.2% of GDP as output increased by 43% and unemployment fell by the same amount. From 2009 through 2012 the average deficit was twice as large, 8.4% of GDP, but output increased by only 6.6% and the unemployment rate fell by only 16% facilitated by a fall in the labor force participation rate. At the same time, the debt to GDP ratio increased from 54% of GDP in 2009 to 71% of GDP by 2012.

The situation was much different during the Great Depression. The greater increase in output and fall in unemployment from 1933 through 1937 left the debt ratio at 42% of GDP, unchanged from what it had been in 1933, and the downward trend in unemployment leading up to 1937 suggests that it may have been possible for the economic system to have grown out of the Great Depression by 1941, without a substantial increase in the ratio of debt to GDP, if it were not for the cutback in government expenditures and the actions of the Federal Reserve in 1937 and 1938.

The difference between then and now is the way in which the deficit was managed during the Great Depression by increasing taxes as non-investment government expenditures were increased and, as much as was possible, using borrowed money only to finance roads, highways, bridges, the Hoover and Grand Coulee Dams, TVA, Rural Electrification, and countless other public investments in physical infrastructure that not only increased employment but increased productivity dramatically in a way that served us exceedingly well in the 1940s during World War II. The government could have done more during the 1930s to mitigate the disaster of the Great Depression, and many mistakes were made, but the way in which the federal debt was managed by increasing taxes during the depression was not one of them.[6]

This is the lesson that should have been learned from the 1930s, not that deficits stimulate the economy. After all, any economist who has thought about it knows that deficits do not stimulate the economy. The deficit is nothing more than the difference between the federal government's current receipts and expenditures. This difference does not stimulate anything. It is simply an effect that results from the interactions between the tax and expenditure policies of the federal government and the rest of the economic system. It is the tax and expenditure policies of the federal government that have causal effects on the economic system, not the deficit that results from these policies. The failure to keep the causal relationship between the deficit and policies clearly in mind has led to a very serious problem.

From the beginning of the current crisis, economists on the left have argued against austerity in a way that leaves the impression that they believe that debt and deficits don't matter and that, somehow, it's the deficits and rising debt that, for better or for worse, affect the economic system rather than the policies that create the deficits and rising debt that have these effects. This has led to a very serious problem in that it has made it impossible to focus the attention of the electorate on what is truly important, namely, the economic policies that are required to deal with our economic problems. By arguing in favor of increasing deficits and debt and not concentrating on the policies that are required to deal with our economic problems we have, in fact, ended up with policies that increase debt and do not solve our economic problems. This is clearly what has been happening in Europe and at home since 2010, and there is no reason to think it's going get better at home as we head into the 2016 election as long as those on the left continue to try to convince the American people that we don't have to worry about the deficit and debt instead of arguing for the policies that will provide and fund the government programs and services that people care about.

The failure to keep the causal relationship between the deficit and policies clearly in mind also seems to have led economists to have missed a second lesson that should have been learned from the 1930s. It was the 50% increase in government expenditures that took place from 1932 through 1936[7] that led to the economic recovery from 1933 through 1937, not the deficits that resulted from the depressed economy. Similarly, it was the cutback in government expenditures as Social Security taxes were phased in and other tax receipts increased (combined with the doubling of reserve requirements that occurred from 1936 through 1938) that caused the economic downturn in 1938, not the reduction in the deficit that resulted from the failure of government expenditures to increase as tax receipts increased. This is the lesson that should have been learned from the disaster of 1937, not that we don't have to worry about deficits and debt.

When we look at the way in which the Great Depression of the 1930s was actually brought to an end we find that there was a dramatic increase in federal debt from 42% of GDP in 1937 to 111% of GDP in 1945, but it was not this increase in federal debt that ended the depression and led to the prosperity that followed World War II. It was 1) the dramatic increase in government expenditures that took place during this period, from 8.5% of GDP to 41%, combined with 2) the comprehensive system of wage and price controls that were put in place during the war, and 3) the tax increases that began in 1932 and continued throughout and following the war that ended the depression and led to the prosperity that followed. Without the tax increases, the federal debt would have grown to astronomical levels during World War II, and without the tax increases combined with wage and price controls, it would have been impossible to achieve the reduction in the concentration of income and the kind of economic stability achieved during the war that made it possible to deleverage the private sector during the war.

As I have attempted to explain in Where Did All The Money Go?, today we are faced with the same kind of situation we faced in the 1930s when the boom and bust cycle of economic instability came to an end, and the economy stagnated for want of a distribution of income capable of providing the domestic mass markets needed to achieve full employment in the absence of a speculative bubble. The changes in tax, regulatory, and international policies that have taken place over the past forty years have led to a situation in which, given the state of mass-production technology in our economy, the existing distribution of income and our current account deficit do not provide the mass markets needed to achieve full employment in the absence of an increase in debt relative to income. Since it would appear that we have reached a point at which a further increase in non-federal debt relative to income is unsustainable, the only way the full employment of our resources can be achieved today is through 1) continually increasing our current account surplus (reducing our current account deficit) to compensate for the effects of the increased concentration of income on our domestic mass markets, 2) continually increasing federal debt relative to income to offset the effects of the increased concentration of income, or 3) reducing the concentration of income. The alternative is to allow our domestic mass markets to shrink and, thereby, reduce our ability to utilize the benefits of mass-production technologies as our resources are transferred out of the mass-production industries that serve the bulk of the population and into those industries that serve the wealthy few.

The only sustainable solution to our employment problem that also has the potential to improve the standard of living of the vast majority or our population is to implement economic policies that reduce both our current account deficit and the concentration of income. As has been noted above, our current account deficit can be reduced through international negotiations and the imposition of sanctions against those who manipulate their exchange rates, and the concentration of income can be reduced by increasing both government expenditures and taxes in ways that are consistent with achieving this end.But the American people will not vote for the increases in government expenditures and taxes needed to reduced the concentration of income unless they fully understand that 1) it is essential to reduce the concentration of income in order to achieve economic growth and stability and 2) we need to increase government expenditures in order to provide the essential government programs and services that people care about and that are essential to our economic and social wellbeing such as national defense, Social Security, Medicare, physical infrastructure, public education, public health, law enforcement, and aid to the needy.

Once these two things are clearly understood by the American people, the need to increase taxes and the kinds of tax increases needed become self evident, but only if the electorate also understands that we must raise taxes in order to stabilize the debt relative to income as we expand and improve the essential government programs and services that people care about. This means that those on the left who favor the kinds of policies I have proposed must stop confusing the issue by trying to convince the American people that we don't have to worry about deficits and debt or that deficit spending is good for the economy. We've been there. Done that. It hasn't worked!

What needs to be done is to convince the American people that we must expand and improve the government programs and services that they care about and that these expansions and improvements must be paid for by increasing the taxes on those who have benefited the most from the epidemic of fraud created by the Republican policies implemented over the past forty years. That's the kind of thing the Democrats did in 1930s, and we got the New Deal as a result.

Since 2009, the Democrats have produced only the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2011. These are two very important pieces of legislation, but both are at risk if the Democrats lose yet another election and the Republicans take over the federal government in 2016.

Endnotes

[1] In effect, the baseline scenario is designed to examine the implications of current law on the federal budget over time, and the alternative fiscal scenario is designed to examine the implications of past and current policies and practices on the federal budget over time. According to the CBO's 2014 Long-Term Budget Outlook baseline scenario projections:

The total amount of federal debt held by the public is now equivalent to about 74 percent of the economy’s annual output, or gross domestic product (GDP)—a higher percentage than at any point in U.S. history except a brief period around World War II and almost twice the percentage at the end of 2008.

If current laws remained generally unchanged in the future, federal debt held by the public would decline slightly relative to GDP over the next few years, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects. After that, however, growing budget deficits would push debt back to and above its current high level. Twenty-five years from now, in 2039, federal debt held by the public would exceed 100 percent of GDP, CBO projects. Moreover, debt would be on an upward path relative to the size of the economy, a trend that could not be sustained indefinitely. (CBO 2014, p. 1)

And according to the CBO's alternative fiscal scenario projections:

Under one set of alternative policies . . . deficits excluding interest payments would be about $2 trillion higher over the next decade than in CBO’s baseline; in subsequent years, such deficits would exceed those projected in the extended baseline by rapidly growing amounts. . . .

Under a different scenario, budget deficits would be smaller than those projected under current law . . . .

Under yet another scenario, with twice as much deficit reduction . . . CBO projects that federal debt held by the public would fall to 42 percent of GDP in 2039. . . . (CBO 2014, p. 3)

And just what are the assumptions that underlie these various projections:

Unless substantial changes are made to the major health care programs and Social Security, spending for those programs will equal a much larger percentage of GDP in the future than it has in the past. At the same time, under current law, spending for all other federal benefits and services would be on track to make up a smaller percentage of GDP by 2024 than at any point in more than 70 years. . . .

To put the federal budget on a sustainable path for the long term, lawmakers would have to make significant changes to tax and spending policies . . . .

The size of such changes would depend on the amount of federal debt that lawmakers considered appropriate. For example, lawmakers might set a goal of bringing debt held by the public back down to the average percentage of GDP seen over the past 40 years—39 percent. Meeting that goal by 2039 would require a combination of increases in revenues and cuts in noninterest spending, relative to current law, totaling 2.6 percent of GDP in each year beginning in 2015 . . . If those changes came entirely from revenues, they would represent an increase of 14 percent from the revenues projected for the 2015–2039 period under the extended baseline. If the changes came entirely from noninterest spending, they would represent a cut of 13 percent from the amount of noninterest spending projected for that period. . . . (CBO 2014, p. 5 emphasis added)

It should be noted that since only 96% of federal revenues came from taxes since 2014, it would required a 14.6% increase in taxes to increase total revenues by 14% if the increase were to come from taxes alone. The discussion in the text assumes that all of the increase has to come from an increase in taxes, hence, a 14.6% tax increase is assumed in the text rather than the CBO's 14% increase in federal revenues quoted above. To the extent that the 14% increase in federal revenues could be obtained from other sources the requisite increase in taxes would be less than 14.6%. The Excel workbook used to breakdown the federal budget in the following chart can be downloaded by clicking here.

[2] Whereas GDP is the gross income generated in production of current output it exceeds that amount of income actually earned by the loss of the capital stock that is worn out through the process of producing that output. For this (and a few other minor reasons) GDP over estimates the income actually earned in producing current output, which is designated as the National Income. Personal Income is the portion of earned income (i.e., National Income) that is actually received by people which excludes retained earnings by corporations and includes various forms of transfer payments. See the Bureau of Economic Analysis's

"A Guide to the National Income and Product Accounts of the United States" for an explanation of these various concepts of national income within the National Income and Produce Accounts. The Excel workbook used to make the calculations for these graphs can be downloaded by clicking here.[4] Eliminating the special treatment of dividends and, especially, capital gains, when combined with 1) a financial transaction tax on trades in financial instruments, 2) the elimination of the carried interest loophole, and 3) adding tax brackets at the top of the income tax system would have the added benefit of reducing the single most powerful incentive that motivates the fraudulent, reckless, and irresponsible behaviors that lead to financial crises and, ultimately, to the kind of economic stagnation we are in the midst of today—namely, the ability to make massive fortunes from these kinds of behaviors. And adding a substantial increase in estate and wealth taxes to this mix will have the added benefit of reducing the tendency toward the establishment of dynastic wealth which tends to increase the concentration of income. And most important, these tax measures, combined with and the elimination of income caps on payroll taxes, will have the added benefit of strengthening our mass markets to the extent they reduce the need to increase taxes on the rest of the income distribution and, thereby, allow the purchasing power of the vast majority of the population to grow. At the same time, to the extent these measures reduce deficits and the federal debt they will also reduce the transfer burden from taxpayers to those who hold government bonds. See Where Did All The Money Go? for a thorough discussion of the importance of these measures in providing economic stability and growth and also A Note on Taxing Corporations.

[5] This is particularly so in the midst of the kind of economic catastrophe we experienced during the 1930s and are experiencing today in which there is a fundamental imbalance in the distribution of income that makes it impossible to maintain full employment in the absence of an increase in debt relative to income. See: Where Did All The Money Go?.

[6] The economics of the Great Depression are discussed extensively in Where Did All The Money Go? with particular emphasis on the way in which the concentration of income inhibited the economic recovery during that depression just as it is inhibiting the economic recovery today.

[7] Federal outlays increased by only 21% from 2008 through 2013 and have actually been allowed to fall since 2013.