Correspondence With

Douglas J. Besharov

From: George H. Blackford

Sent: Tuesday, August 20, 2013 3:47 PM

To: besharov@umd.edu

Subject: CSPAN Capital Journal interview

Douglas J. Besharov, Professor

School of Public Policy

University of Maryland

College Park, MD 20742

Dear Professor Besharov,

I was completely taken aback by your argument to the effect that federal spending on WIC and SNAP is out of control. (CSPAN Capital Journal interview, http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/NutritionPr) This is especially so with regard to your conclusion that if we don’t reform the WIC program to keep people who make $40,000 to $60,000 a year from receiving its benefits “we will go broke.”

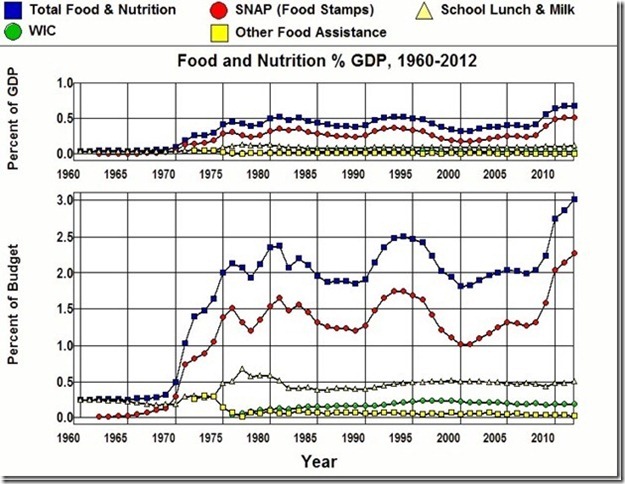

The graphs below break down the Food and Nutrition portion of the federal budget and plot its components since 1960 as a percent of total federal expenditures and of GDP:

Source: Office of Management and Budget’s Tables: (11.3 3.2 10.1)

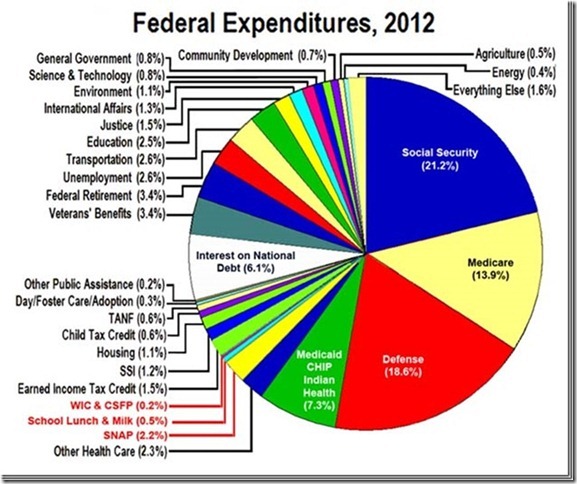

The following pie-chart breaks down total federal expenditures in 2012 in terms of its major components:

Source: Office of Management and Budget’s Tables: (11.3 3.2 10.1)

Even a casual look at these graphs and pie-chart shows quite clearly that, contrary to the impression you left in your interview, there has not been a dramatic increase in the Food and Nutrition portion of the federal budget since the 1970s. Federal expenditures on Food and Nutrition relative to the economy and as a fraction of the federal budget peaked in the 1980s and again in the 1990s. There is not an increasing trend here, and before the current economic crisis hit this component of the federal budget was, in fact, 20% below its previous peaks in the 1980s and 1990s. Nor has there been a dramatic increase in the WIC program as our economy has grown since the 1970s.

And when I look at the pie-chart, I am astounded by the idea that runaway spending on the 2.2% slice that goes to SNAP presents a major fiscal problem for the federal government or that the tiny sliver of the budget (0.2%) that goes to WIC threatens the government’s solvency—that if we don’t control spending on WIC “we will go broke.” Do you honestly believe this to be the case? If so, why? I would think that this notion is particularly absurd when it comes to WIC. Aside from the fact that spending on WIC is relatively insignificant in the federal budget, funding for this program reached its peak in terms of the budget and the economy in the 1990s and has fallen almost continuously since then to the point that, today, it is 20% below where it was in 1996.

I also think it is fairly clear from these graphs that the current spike in the Food and Nutrition component of the budget is an indication of the need for these programs, not an indication of runaway spending, as you argue. This portion of the budget has risen and fallen with fluctuations in the economy since the food stamp programs came into full maturity in the 1970s. Do you honestly believe that this pattern has somehow changed, and spending has increased recently because of a lowering of the requirements for these programs rather than because more people are in trouble as a result of the fact that we are in the midst of the worse depression since the 1930s?

I would also note that your comparison of the “$100 million” spent on WIC in 1972 to the $7 billion we spent today is particularly specious. We spent $79.2 billion on defense in 1972 and $678 billion in 2012. Does that mean spending on defense is out of control? I don’t think so. Defense took up 34% of the federal budget and 7% of our total GDP in 1972. Today it’s only 19% of the budget and 4% of GDP. At 19% of the budget and 4% of GDP our defense budget is much less of a burden today than it was in 1972, and in spite of the fact that we are spending nine times more in nominal dollars today than we were in 1972, our military forces have been cut by a third since then.

Making these kinds of comparisons of programs like WIC in terms of nominal values ignores the effects of rising prices and the increased need for the program caused by population growth and the stagnation of average real income for the bottom 40% of the income distribution in the face of the dramatic increase in the labor force participation rate of women. It also ignores our ability to pay as the total income generated in the economy today is 13 times, in nominal terms, what it was in 1972. And choosing 1972 for the year of comparison for WIC is particularly inappropriate. As you noted, the WIC program wasn’t even created until 1972. It was the Commodities Supplemental Food Program (CSFP) that was begun in the 1960s to feed expectant mothers, not WIC, and that program was grossly underfunded. WIC came into being in 1972 in response to the inadequacies of CSFP, and it took until 1976 for the WIC program to even show up as a separate item in the OMB’s Table 11.3—Outlays for Payments for Individuals from which the above graphs were constructed. What possible use can there be in comparing the nominal amount of money spent on this program in the year it became law, before it became fully funded with the amount we are spending on it today?

As for the notion that four-person families making $40,000 to $60,000 a year have taken over the food stamp program, the rules governing eligibility for SNAP are spelled out quit clearly on the USDA website. A four-person household is eligible for food stamps only if its net-income is equal to $1,921 per month or less. Since a gross income of $40,000 a year amounts to $3,333 a month (40000/12=3333.33), the only way a four-person household can be eligible for food stamps is if it can come up with $1,412/mo (3333-1921=1412) in deductions to arrive at maximum allowable monthly net income. Since the Standard Deduction in calculating SNAP benefits is 20% of earned income plus an additional $160, this leaves a $586 deficit (1412-160-.2x3333=585.4) for a four-person household making $40,000.

There are only four kinds of deductions that allow a deficit this large to be made up: The household can deduct 1) “dependent care [expenses]. . . when needed for work, training, or education”, 2) “Medical expenses for elderly or disabled members that are more than $35 [per] month”, 3) “Legally owed child support payments”, 4) “[e]xcess shelter costs that are more than half of the household's income . . .” That’s it!

These are the expansions of the SNAP program that you insinuate have led to out-of-control spending on those who make $40,000 to $60,000 a year, and these deductions only apply if there is an elderly or disabled person in the household. If gross income is above $29,976, a four person household that does not include an elderly or disabled person is not eligible for SNAP whatever its deductions may be.

And what happens if your household is raking in $40,000 a year and is able to come up with an additional $586 worth of deductions because, say, the medical expenses of an elderly or disabled member run to $621/mo? You have to subtract 30% of net income from the maximum benefit allowed, which is $669 per month, to arrive at the actual benefit received, which will equal $93/mo (669-.3x(40000/12)-160-.2x(40000/12)-(621-35)=92.8). This is less than $25 a month for each member of the household! What’s more, if you do the math you will find that in order to receive the full benefit of $668/mo there would have to be medical bills for an elderly or disabled member of the household equal to $2,541/mo, and if you were making $60,000/yr the monthly medical bill would have to be $1,921/mo in order to rake in that $92/mo food stamp benefit and $3,875/mo in order to reap the full benefit of $668/mo.

It seems to me that anyone who is making $40,000 or $60,000 a year and paying out $7,448 or $23,448 a year in out-of-pocked medical bills for an elderly or disabled family member while trying to provide food, clothing, and shelter for four people out of the remaining $32,552 or $36,552 is undoubtedly under a great deal of stress and could probably use a little help. It also seems to me that if they are in this situation and paying out $30,500 or $46,500 a year in out-of-pocket medical bills and trying to make it on the remaining $9,500 or $13,500 they are in desperate straits and definitely need some help. I would think that the least we could do for them would be $92 or $668 a month in food stamps. Where’s the problem here? The idea that if we give these families food stamps they are going take our money and run out and buy “uncooked lobster” is absurd. How many four-person families could there possibly be on food stamps who make $40,000 to $60,000 a year while paying huge medical bills to care for elderly or disabled family members? The idea that there are so many they are bankrupting the system is just silly.

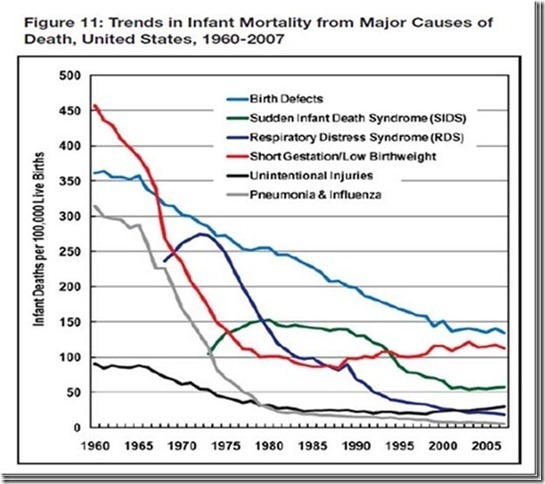

I am at a total loss as to why you or anyone else would advocate increasing the eligibility requirements for the SNAP and WIC programs, and especially for the WIC program. As you can see in the following figure, the infant mortality rate in this country was atrocious before the food stamp and WIC programs were initiated:

Source: Health Resources and Services Administration.

Not only have food stamps and WIC, along with a rising level of prosperity at the bottom 40% of the income distribution through the 1960s, gone a long way toward eliminating the malnutrition problem (a problem that you acknowledged in your interview was endemic in our society in the 1950s and 1960s) there is every reason to believe that food stamps and WIC contributed significantly to the dramatic decrease in infant deaths associated with Short Gestation/Low Birth Rate from around 220 infant deaths per 100,000 live births 1970, to less than 100 by the time the funding for these programs began to level off in the 1980s. These are not inconsequential statistics. There were 3,953,590 live births in 2011. If the infant death rate had stayed at 200 infant deaths per 100k live births, as it was in 1973 when the income of the bottom 40% of the income distribution began to stagnate, we would have seen some 7,907 infants die in 2011 alone caused by complication from Short Gestation/Low Birth Rate instead of the 4,116 deaths implicit in the CDC’s estimate of an infant mortality rate of 104.1/100k live births in 2011.

Why would you want to mess with programs that have helped to dramatically reduce the level of malnutrition in our country and to save the lives of some 3,800 infants in 2011 and of a comparable number of infants, relative to the number of live births, in each year since the late 1970s?

Your argument to the effect that we should cut people off the SNAP and WIC programs who don’t need them so that we can spend the money on the truly needy is truly insidious. The people who get these benefits who don’t need them, generally, don’t need them because they get them, and if we were to try to take them away to give them to those who truly need them, rather than expand the programs to meet the needs of those who are left out, we would end up going in circles and probably end up back where we were in the 1960s.

And I see no reason to believe there is some optimum gross-income cutoff level somewhere below $40,000, as you have suggested, that can be used to define who needs and should get the benefits from these programs. If there is to be an arbitrary cutoff level it should be set in terms of net income, not gross income. Why does it make sense to think that a four-person, $40,000 household paying out-of-pocked medical bills of $30,000 should not get food stamps (in the absence of an elderly or disabled person in the household) while a similarly situated $20,000 household paying $10,000 out-of-pocket medical bills should get food stamps? What difference does gross income make in this situation? Why do you insist in talking about gross income in discussing the extravagances of SNAP instead of net income?

You seem upset at the long lines and wasted time going through the bureaucracy for those who are truly in need to get their benefits, and at the same time complain about the fact that the income test in the WIC program takes place only once a year. How often do you think it would be appropriate to investigate the income of the recipients in this program? Should it be monthly? Weekly? Should we hire people to follow recipients around on a daily basis to make sure they aren’t cheating? How much longer will the lines get, and how much more time will be wasted if we were to insist on a more frequent income test? What will it cost to increase the bureaucratic hassle in this way and how much will it save? It is very unlikely that we will be able to save any money at all by doing this without forcing many out of the program who truly need the food and the counseling. And what will be the effect on the infant death rate in this country if we do manage to save some money in this way?

In the end, I just don’t understand why you would want to cut people off SNAP and WIC, given all of the good these programs have done. This is especially so with regard to WIC. In spite of this program we still rank 28th among the OPEC countries when it comes to infant mortality and 51st among all countries, and complications associated with Short Gestation/Low Birth Rate is still the second largest cause of infant deaths in our country. Given this record, I would think that you would want to expand the tiny sliver of the budget that goes to WIC to all expectant mothers and families with infants, irrespective of income, rather than cut it. Countries that do this sort of thing, such as France, have substantially lower infant death rates than we do. France’s infant mortality rate is 40% below ours, and it would appear from looking at the above figure, that Short Gestation/Low Birth Weight is associated with somewhere between 30% and 40% of the infant deaths in the United States. I suspect this is not a coincidence.

Personal income in the United States amounted to $13,191.3 billion in 2011, and total federal expenditures came to $3,603 billion. This means that the total tax liability created by the 2.9%/$103.1 billion we spent on the Food and Nutrition Assistance portion of the federal budget 2012 amounted to only 0.78% of our personal income, and the amount that went to WIC only 0.2% [of the federal budget]. I would think this is a rather small price to pay in taxes for all of the good these programs have done toward eliminating malnutrition and reducing number of infants that die in our country. It also seems to me if that if we are able to serve over 50% of the infants born in this country through WIC with the current funding, doubling the 0.2% of the federal budget that goes to WIC would be more than enough to make the counseling part of this program, and much of the food as well, available to all expectant mothers and mothers of infants, irrespective of income, and this would be a very small price to pay for the benefits we could expect to see from doing this. Why would you object to this in view of how little is spent on this program and the amount of good it does in terms of saving the lives of infants?

Finally, I would appreciate your telling me where you got the idea that suppliers of infant formula offer to sell it through the WIC program at a loss in order to get shelf space in supermarkets and, thereby, are forced to make up the difference by charging higher prices to those who don’t participate in the WIC program. The idea that a business can make a profit by offering to service over 50% of the market at a loss as it makes up the difference by selling to the rest of the market at a higher price while its competitors are free to ignore the WIC market and service the rest of the market at a reasonable price, seems ludicrous to me. I would think that—shelf space or no shelf space—any business that tried to make money in this way would be able to sell virtually nothing at its higher price outside the WIC market and would be driven out of business faster than it could come up with such a stupid idea in the first place.

You don’t have to have a Ph.D. in economics to realize that if Abbott Laboratories wins the WIC contract by offering to sell Similac, that costs $50 a can to produce, to WIC customers for $40 and then increases the price to $80 for the rest of the public, and Mead Johnson, who didn’t get the WIC contract, decides to sell Enfamil for a reasonable price of $60 a can to the rest of the public, people who don’t get WIC are going to buy from Mead, not from Abbott. Mead is going to make $10 profit on every can of formula it sells to the non-WIC customers (47% of the market) and Abbott is going to make a $10 loss on every can it sells its WIC customers (53% of the market), and a $30 profit on every can they can sell to anyone foolish enough to pay the extra $20 they can save if they buy from Mead.

Seriously, what would you do in this situation, pay $80 for Similac or $60 for Enfamil? Do you really believe that people aren’t going to find out that Enfamil is $20 cheaper just because Similac has better or more shelf space? Mead would make a fortune in this situation and Abbott would go broke if it tried to implement such a foolish scheme.

You preface your discussion of this problem with the statement: “Unless you believe the economists who say it would be less expensive without the government supporting it we need to provide this subsidy.” I would deeply appreciate your sending me a reference if you know of any economic analysis or study that has made the above argument as I would really like to know who the economists are that have come to this conclusion, if there are any, and why they think such a seemingly absurd scheme would work or is actually working in the infant formula market today. I can see how an economist might argue that the existence of WIC facilitates price discrimination on the basis of income or that there may be diseconomies of scale in the industry, but I would be very surprised, indeed, shocked to find one who would argue that companies can sell below cost to WIC and make up the difference by charging a higher price to others in this situation.

Sincerely,

George H. Blackford, Ph.D.

From: Douglas J Besharov

Sent: Tuesday, August 20, 2013 5:41 PM

Subject: RE: CSPAN Capital Journal interview

Dear Dr. Blackford,

Thank you for your very civil note of disagreement. I apologize for not having the time to respond to the points you make. I suppose that, if you think having more than 50% of all American newborns on WIC does not suggest a program that is poorly target, we will have difficulty agreeing on very much. In any event, I did coauthor monograph on the subject that tries to make the points I summarized on the program. See http://www.amazon.com/Rethinking-WIC-Evaluation-Children-Evaluative/dp/0844741493

Best wishes,

Doug B

From: George H. Blackford

Sent: Thursday, August 22, 2013 2:36 PM

To: Douglas J Besharov

Subject: Fw: CSPAN Capital Journal interviewDear Professor Besharov,

I appreciate your prompt and considerate response to my concerns regarding your CSPAN, Capital Journal interview. I must say, though, that I don’t share your pessimism with regard to the difficulty of our being able to agree on very much. It seem to me that when two honest and reasonable people who share common goals discuss ways to achieve those goals there is much that they should be able to agree on even if they have different ideas about how those goals should be achieved.

I’m not at all sure, for example, that I would not agree with you that the WIC program is poorly targeted. At the same time, we may or may not agree on how to deal with this problem and, at the same time, achieve the goals of the program in the most efficient manner.

You seem to believe that this can be accomplished by increasing the restrictions on who is eligible for the program and increasing the bureaucracy so as to enforce the added restrictions, whereas I tend to think that the goals of the program may be more efficiently obtained by reducing the restrictions and decreasing the bureaucracy, but I am not wedded to this view. If you can show me a better way to achieve those goals, I’m willing to listen. And even if we can’t come to an agreement on this issue we should at least be able arrive at a point where we can agree to disagree.

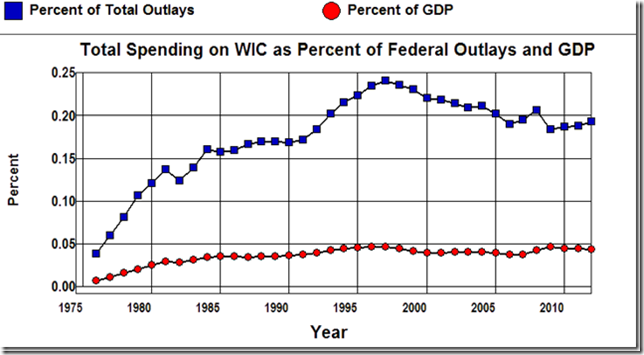

At the same time, when you see a graph like this:

Source: Office of Management and Budget’s Tables: (11.3 10.1)

that shows the total spending on the WIC program as a percent of total federal outlays and GDP, I don’t see why you would have any difficulty agreeing with me that it was a mistake to argue that total spending on the WIC program is out of control because of reduced eligibility requirements and that if we don’t increase these requirements we will go broke in view of the fact that there has been a downward trend in spending on this program as a fraction of the budget since 1996, and total spending on this program is less than two tenths of one percent of the federal budget.

It is inconceivable to me that anyone would try to defend the proposition that out-of-control spending in two tenths of one percent of the budget that has been showing a downward trend in the budget for the past seventeen years will cause the federal government to go broke if we don’t do something about it.

I would also note that the way I tend to view this kind of problem is not from some kind of left-wing, radical/Marxist perspective. The pros and cons of bureaucratic restrictions versus universal eligibility for social insurance programs are examined in detail in Peter Lindert’s Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century where Lindert is a rather mainstream academic, and the idea of universal eligibility lies at the very core of Milton Friedman’s concept of a Negative Income Tax, and not many people consider Friedman to be, or to have been, God rest his soul, a flaming liberal.

Nor do I see why it would be difficult for us to come to an agreement on the importance of gross income versus net income in determining the need for food stamps. It seems to me that listening to reasoned arguments on both sides of an issue like this is the way one approaches the truth when there are differing views on the subject. And as for whether economists argue that companies sell at a loss in the WIC market so that they can charge higher prices in the non-WIC market rather than that higher prices in the non-WIC market come about because of price discrimination on the basis of income or decreasing returns to scale, I will gladly look at the research in this area if you can find an economist who has argued that firms sell at a loss to see if it makes sense, but I must say that the economics seems pretty clear in this situation.

In any event, I have not read your book as yet, but have ordered it from Amazon. I will get back to you when I finish it which, unfortunately, will probably take some time since I will be rather busy for the next few weeks. Who knows? Maybe you will change my mind. We will see.

All the best,

George H. Blackford, Ph.D.

From: Douglas J BesharovSent: Thursday, August 22, 2013 6:41 PMSubject: RE: CSPAN Capital Journal interviewDear George (and do call me Doug),

Well, I am delighted that you ordered my monograph. I only wish I rec’d a royalty!

I am sorry that I can’t answer your e-mails with the detail they deserve. One point I’d make, however, is that any dollar spent on a lower-priority purpose (such as higher-income WIC recipients) can’t be spent somewhere else (such as lower-income WIC recipients). That’s a central argument of our monograph, btw.

Best,

D

From: George H. BlackfordSent: Thursday, August 22, 2013 7:15 PMTo: besharov@umd.eduSubject: Re: CSPAN Capital Journal interviewDear Doug,Thanks for the comment. I will wait until I read the argument in full before I comment on it.All the bestGeorgeFrom: George H. Blackford

Sent: Monday, September 16, 2013 8:59 PM

To: besharov@umd.edu

Subject: CSPAN Capital Journal interviewDear Doug,I have now read your book, Rethinking WIC, and was pleasantly surprised to find how thorough it is. I was somewhat disappointed by its negative tone in Part One, systematically playing down research results that were favorable to WIC and emphasizing those that were unfavorable, but was very impressed with the inclusion in Part Two of the critical comments by the researchers that you examine in Part One. I could make a list of those areas where I believe you have gone astray, but I see no need to do so as the comments in Part Two include and go beyond any criticisms I might have of my own. By including those comments I think you have done a very good job in your analysis of the WIC program in your book, and I will, in fact, recommend it to others who may be interested in this program.I must say, however, that the observation in your last email to the effect “that any dollar spent on a lower-priority purpose (such as higher-income WIC recipients) can’t be spent somewhere else (such as lower-income WIC recipients)” is not at all relevant when it comes to the WIC program. I can see how you might think this sort of reasoning is important if you believe that out of control spending on this program is going to cause us to go broke, but when you look at the numbers in the real world and find that

- WIC takes up only 0.2% of the federal budget;

- there has been a downward trend in in spending on this portion of the budget over the past 17 years, and

- the tax liability created by the 0.2% of the federal budget spent on WIC is only 0.05% of personal income,

it should at least be apparent, if not obvious that choosing between higher-priority and lower-priority purposes is a false choice here. Given the trivial amounts spent on WIC, money is not the issue, or at least it should not be. This is especially so in view of the fact that we are talking about a program that is attempting to deal with unacceptable rates of infant mortality and malnutrition among young children.

As you have indicated in your book, there are many ways that it may be possible to improve the outcomes in the WIC program, but I found nothing in you analysis or review of the literature that indicates infant mortality and malnutrition among young children in our country is solely determined by low income, even if this is the most important determinant. Nor did I find anything that indicates cutting benefits to those with higher incomes will improve outcomes with regard to these problems, even if those with a higher income are of a lower priority. What’s more, given the modest amounts that are actually spent on WIC, I see no reason to believe benefits to higher income earners should not be expanded rather than cut, especially when it comes to the educational and counseling programs offered by this program, and from a purely economic point of view, there is every reason to believe that infant formula would be a lot less expensive in this country if the food supplement portion of the program were made available to all families with children irrespective of income since companies could then be prevented from practicing price discrimination on the basis of income.Why would you choose to ignore those factors that lead to infant deaths and malnutrition among young children that are independent of income in a situation where the United States, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, ranks 28th among the OPEC countries when it comes to infant mortality and 51st among all countries and, at the same time, devotes such a tiny fraction of its national resources toward solving this problem? Given the circumstances, this does not seem to me to be a reasonable position to take if one is truly interested in the welfare of infants and children. Am I missing something here?Sincerely,George