From

Chapter 2

Appendix on International Exchange

Exchange Rates and International Trade

The exchange rate between the American dollar and a foreign country's currency is nothing more than the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars. If the Chinese must pay ¥10 to purchase one dollar of our currency, the YUAN/USD exchange rate will be ¥10 per dollar. Similarly, if the EURO/USD exchange rate is €0.75 per dollar that means that Europeans must pay €0.75 to purchase one dollar of our currency. In general, the higher our exchange rate the higher the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars; the lower our exchange rate the lower the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars.

This works in reverse, of course, when it comes to us buying foreign currencies. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar then we can purchase ¥10 for one dollar, which works out to a price of $0.10 per yuan. If the exchange rate is ¥5 per dollar we can only purchase ¥5 for one dollar, which works out to a price of $0.20 per yuan. In general, the higher our exchange rate the lower the price we must pay in our currency for a foreign currency; the lower our exchange rate the higher the price we must pay in our currency for a foreign currency.

Exchange rates are extremely important in determining the flow of international trade because, in general, the producers of goods in foreign countries must pay their costs of production (employees, suppliers, etc.) in their domestic currencies. Those costs, in turn, determine the prices in terms of their domestic currencies at which they are willing to sell the goods they produce. If we wish to purchase goods from a foreign country we must pay the prices in terms of their domestic currencies at which producers are willing to sell. Similarly, if foreigners wish to purchase goods from us they must pay the prices in terms of the American dollar at witch American producers are willing to sell. As a result, the exchange rates between currencies determine the prices people must pay in their own currencies for the goods they import from other countries.

To see how this works, consider a bushel of wheat that a Chinese producer is willing to sell for ¥20. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar, someone in the United States who wished to purchase that bushel of wheat has to come up with $2 to purchase the ¥20 necessary to pay the Chinese producer ¥20. The dollar price of that bushel of Chinese wheat in this situation will be $2/bu. If, instead, the exchange rate is only ¥5 per dollar, the American purchaser has to come up with $4 to purchase the ¥20 needed to purchase that bushel of Chinese wheat. This means the dollar price of that bushel of Chinese wheat will increase to $4/bu. even though the yuan price of wheat in China hasn't changed. In general, the higher our exchange rates the lower the prices in dollars we must pay for foreign goods; the lower our exchange rates the higher the prices in dollars we must pay for foreign goods.

Again, this works in reverse when it comes to the Chinese buying from us. If the price of a bushel of wheat in the United States is $3, and our exchange rate with China is ¥10 per dollar, someone in China who wishes to purchase a bushel of American wheat will have to come up with ¥30 to purchase the $3 needed to pay the American price of wheat, and the yuan price of American wheat will be ¥30/bu. But if our exchange rate falls to ¥5 per dollar the Chinese importer will have to come up with only ¥15 to purchase the $3 needed to purchase the American wheat, and the yuan price of American wheat will fall to ¥15/bu. even though the dollar price of wheat in the United States hasn't changed. In general, the higher our exchange rates the higher the prices foreigners must pay in their currencies for our goods; the lower our exchange rates the lower the prices foreigners must pay in their currencies for our goods.

The point is, exchange rates play a crucial role in determining whether or not it is profitable for us to import goods from foreign countries or foreigners to purchase the goods we export: At a given set of foreign and domestic prices, when our exchange rates go up, the dollar prices of goods produced in foreign countries go down, and it becomes more profitable for us to import foreign goods; when our exchange rates go down, the dollar prices of goods produce in foreign countries go up, and it becomes less profitable for us to import foreign goods. At the same time, when our exchange rates go up, the foreign currency prices of our goods go up, and it becomes less profitable for foreigners to purchase our exports; when our exchange rates go down, the foreign currency prices of our goods go down, and it becomes more profitable for foreigners to purchase our exports.

Exchange Rates, Wages, and International Trade

The wage rate is nothing more than the price of labor. As a result, exchange rates determine the dollar price of labor (wages) in different countries in the same way they determine the dollar price of any other foreign good. If the price of labor is ¥40/hr. in China and the exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar, it will cost us $4 to purchase the ¥40 that an hour of labor costs in China. This means that the dollar price of Chinese labor will be $4/hr. If the exchange rate is ¥5 per dollar, it will cost us $8 to purchase the ¥40 that an hour of labor costs in China, and the dollar price of Chinese labor will be $8/hr. Thus, an increase in the exchange rate will decrease the price of foreign labor in terms of dollars, just as it will decrease any other foreign price in terms of dollars, and a fall in the exchange rate will increase the price of foreign labor in terms of dollars, just as it will increase any other foreign price in terms of dollars.

This brings us to a very important point, namely, that just because the exchange rate is such that the price of labor is lower in a given country (such as China) when measured in the same currency (either yuans or dollars) than it is in the United States, this does not mean that everything will be cheaper to produce in that country than in the United States. The reason is that the price of labor is only one of the factors that determine the cost of producing something. There are other costs as well, in particular, the costs of natural resources and of capital. In addition, the cost of labor does not depend solely on the price of labor. It also depends on the productivity of labor, that is, on the amount of output that can be produced per hour of labor employed.

The importance of this should become clear when we consider that, in spite of the fact wages are much lower in China than they are in the United States, we do not import wheat from China. The reason is that, in general, capital equipment is scarce and very expensive in China relative to labor, especially the kinds of farm equipment we take for granted in the United States. The scarcity of capital equipment, in turn, means that much of the work that is done by farm equipment in the United States must be done by people in China to the effect that more labor is required to produce a given quantity of wheat in China than is required to produce the same quantity of wheat in the United States.

The fact that it takes more labor to produce a given quantity of wheat in China than it does in the United States means that the dollar cost of labor in producing wheat in China is higher than the dollar price of labor indicates. In fact, when we combined the cost of labor in China (i.e., the price of labor times the quantity of labor that must be employed to produce a given amount of wheat) with all of the other costs of producing wheat—including the cost of farm equipment, land, transportation, energy, taxes, etc.—we find that, given the exchange rate between the yuan and the dollar, it actually costs more to increase the production of domestically produced wheat in China than it does to purchase wheat from the United States. As a result, we do not import wheat from China. Instead, China imports wheat from us. (Coia USDA) This is so even though the dollar price of Chinese labor is far below the dollar price of American labor. [1]

It is the cost of increasing the production of domestically produced goods relative to the cost (measured in the same currency) of purchasing from a foreign country that determine which goods we import from foreign countries and which goods foreign countries import from us, not the relative prices of labor. And the fact that these relative costs are determined by exchange rates means that in order to understand how imports and exports are determined, we must look at how exchange rates between countries are determined as well as how costs within countries are determined. (Smith)

Exchange Rates and International Capital Flows

Since the producers of the goods must be paid in their domestic currencies, a country’s imports must be financed in the foreign exchange market, that is, in the market in which the currencies of various countries are bought and sold. The most important source of demand in this market comes from foreigners who purchase the foreign exchange needed to purchase the country's exports. Similarly, the most important source of supply comes from a country's importers who sell the country's currency in order to obtain the foreign exchange needed to purchase the country’s imports. [2]

When the value of a country's imports is equal to the value of its exports, the supply of foreign exchange from those who purchase the country’s exports will equal the demand for foreign exchange by those who purchase the countries imports, and the country will be able to obtain enough foreign exchange in the foreign exchange market to finance its imports from the sale of its exports. But if the value of a country’s imports exceeds the value of its exports there will be a deficit in its balance of trade, and it will not be able to finance all of its imports in this way. This deficit must be financed, and one of the ways it can be financed is from the incomes earned by individuals and institutions within the country on the investments they have made in foreign countries.

When individuals or institutions in one country own earning assets (investments) that are denominated in other countries' currencies, the earnings on those assets can only be spent in the domestic economy if they are converted into the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market. As they are converted, they contribute to the demand of the country’s currency in the foreign exchange market. By the same token, when individuals or institutions in other countries own earning assets that are denominated in the domestic currency, the earnings on those assets can only be spent in the foreign countries if they are converted into the foreign countries’ currencies in the foreign exchange market. As they are converted, they contribute to the supply of the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market.

A similar situation exists when individuals or institutions simply transfer funds abroad. When an individual sends money to a family member abroad, a business transfers funds to a foreign subsidiary, or a government provides aid to a foreign country in the form of cash it increases the supply of the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market as those funds are converted into foreign currencies by their recipients. As a result, these kinds of international transfers of funds contribute to the supply and demand for a country’s currency in the foreign exchange market in the same way international payments of income contribute to the supply and demand for a country’s currency in this market.

A country’s net exports—that is, the difference between the value of its exports and the value of its imports—plus its net income (similarly defined) on foreign investments plus its net transfers of funds is referred to as the country's current account balance. The significance of this balance is that it defines the extent to which a country is able to pay for its current imports, the current income earned by foreigners who hold earning assets denominated in the country's currency, and its current transfers of funds abroad out of the foreign exchange it receives from the sale of its current exports, the current income it receives from its holdings of earning assets denominated in foreign currencies, and its receipts from current transfers of funds by foreigners.

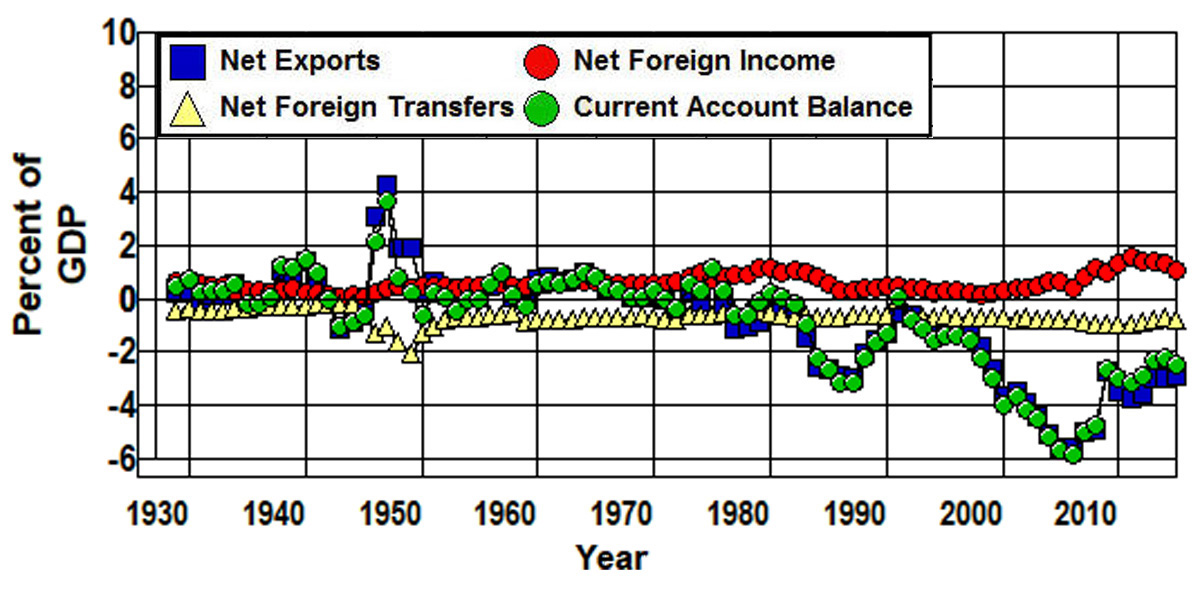

The composition of the current account balance for the United Sates from 1929 through 2013 is shown in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5: U.S. Current Account Balance, 1929-2015.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (4.1)

The extent to which our Current Account Balance has been dominated by our balance of trade (Net Exports) is clear in this figure in that, in most years, these two variables are barely distinguishable in Figure 2.5.

When a country's current account is balanced, all of its current international expenditures can be financed by its current international receipts of foreign exchange, where its current expenditures and receipts are those that are generated through the ordinary process of producing goods, earning income, and transferring income in the international economic system. When there is a deficit in a country's current account, all of the country's current international expenditures cannot be financed through its current receipts. Similarly, when there is a surplus in a country's current account the country receives more than enough foreign exchange from its current receipts to finance its current international expenditures.

By definition, one country's current account deficit is some other country's current account surplus. Countries with current account deficits must finance those deficits in their current account obligations. Since current account deficits cannot be financed through the ordinary process of producing goods, earning income, and international transfers the only way they can be financed is through a transfer of assets from surplus countries to deficit countries. These asset transfers are referred to as international capital flows, and they represent a willingness of foreigners in surplus countries to invest in deficit countries—either directly by purchasing real assets in the country or indirectly by purchasing the country's financial obligations, usually bonds or other forms of debt. Foreign investments of this sort can be used to finance a deficit in a country's current account because the sellers of these assets must be paid in the deficit country's currency just as the producers of a country's exports must be paid in the producers’ domestic currencies.

If a country cannot finance its current account deficit through a current account surplus it means that the demand for its currency in the market for foreign exchange is less than the supply of its currency in this market. In this situation, either its exchange rates must fall (which will make its exports less expensive to foreigners and its imports more expensive in its domestic markets and, thereby, reduce the current account deficit/capital account surplus) or the expected rates of return on foreign investment in that country must increase (which will make foreign investment more attractive and, thereby, increase the willingness of foreigners to finance the current account deficit/capital account surplus) until the demand and supply for its currency is brought into balance in the market for foreign exchange.

Instability in Unregulated International Markets

As is explained in the text, a deficit in a country's balance of trade or in its current account is not, in itself, a bad thing, but there are two situations in which it can become a problem. The first arises from the fact that while decisions regarding current account transactions (imports, exports, and transfers) tend to progress relatively slowly over time, the purchase and sale of financial assets in international markets can be executed almost instantly. As was discussed at the beginning of this chapter, this can lead to serious instability in the markets for foreign exchange as speculation and the concomitant speculative bubbles that culminate in financial panics and economic crises are accompanied by, and are often the result of, dramatic and sudden shifts in international capital flows. (EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

The second situation in which a deficit in a country’s balance of trade or in its current account can become a problem has to do with the way in which foreign investments can be used to manipulate exchange rates. If a country with a current account surplus is willing to make foreign investments it can accumulate assets in deficit countries and, thereby, prevent its exchange rates from rising (deficit countries' exchange rates from falling). This makes it possible for the surplus country to keep the demand for its exports from falling in response to its surplus. The risk in doing this is that, because the assets being accumulated are denominated in foreign currencies, those who accumulate foreign assets in this way will take a capital loss on those assets in terms of their own currency if and when its exchange rates eventually rises (foreign rates fall) since the assets will then be worth less in terms of the domestic currency of the surplus country.

It is worth noting, however, that this potential for capital loss is not necessarily a deterrent to a country artificially suppressing its exchange rate in this way. To the extent the accumulated foreign assets can be transferred to the country's central bank or to its government, it is the central bank or government that will take the capital loss when exchange rates eventually adjust rather than those who earn their incomes in the exporting industries or otherwise benefit from the lower exchange rate.

In addition, as will be explained in Chapter 3, a trade surplus makes it possible for the distribution of income to be concentrated at the top of the income distribution in that, given the state of technology, when a country has a surplus in its balance of trade, full employment can be maintained with a higher concentration of income than in the absence of a trade surplus. It is also worth noting that, as is apparent from Figure 2.3 above, almost all countries have been willing to take this risk vis-à-vis the American dollar in recent years in order to build up their international reserves, stimulate their economies, or maintain the concentration of income within their societies.

Allowing countries to prevent their exchange rates from rising and, thereby, keeping our exchange rates from falling has led to our exchange rates being overvalued in the market for foreign exchange for most of the past thirty-five years as foreign countries have accumulated surpluses in their balance of trade while we have accumulated deficits in ours. As a result, foreign goods have been undervalued in our domestic markets for most of that period which has given importers an unfair, competitive advantage in these markets. This has placed a serious drag on the American economy and has had a particularly a devastating effect on our manufacturing industries. In addition, as we will see in Chapter 3 through Chapter 10, to the extent this drag has contributed to the need for a rising debt to maintain employment, it has also contributed to the instability of the American economy.

End Notes

[1] If it didn’t cost more to increase the amount of domestically produced wheat in China than it costs to purchase wheat from us at the existing exchange rate, the Chinese could save money by increasing the production of domestically produced wheat and cutting back on the amount of wheat they purchase from us. This would give Chinese farmers an incentive to increase the production of domestically produced wheat until it did cost more to increase production at home than to purchase from us.

[2] Since the U.S. dollar is generally used as an international reserve currency by most countries, U.S. dollars are the actual medium of exchange that is used in most international transactions. Thus, importers generally convert their currencies into dollars in order to pay in dollars and exporters generally accept dollars in payment. Ultimately, the dollars accepted by exporters must then be converted to the exporter’s domestic currency if they are to be spent in the exporter’s domestic economy, or, as will be discussed below, converted into some other currency if they are not used to purchase dollar denominated assets. It is this conversion process of foreign currencies into and out of dollars that takes place in the market for international exchange. See Eichengreen for a discussion of the role played by the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency in the market for international exchange.