Chapter 2: International Finance and Trade

The American dollar became undervalued in the markets for international exchange in the 1960s as Europe recovered from the devastation of World War II. This problem came to a head in 1973 when the Nixon administration allowed the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement to collapse along with its negotiable fixed exchange rate system and its provisions for controlling international capital flows. International exchange rates have floated in unregulated markets ever since. While a fixed exchange rate system is highly undesirable in that it severely limits the policy options available to a country in managing its domestic economy, allowing international exchange rates to be determined in unregulated markets has proved to be a disaster. It has led to the international exchange system becoming the largest gambling casino in history. Financial institutions place trillions of dollars of bets in this casino on a daily basis as they direct international capital flows throughout the world. Insiders who gamble in this market can make fortunes, but when things go wrong, the results can be catastrophic. (EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

International Crises and Financial Bailouts

There have been four international financial crises since 1973 in which American financial institutions have bet wrong in this casino. The first was in the early 1980s during the Latin American Debt Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Latin American countries. The second was in 1994 during the Mexican Peso Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves in making loans to Mexico. The third was in 1998 when a single American hedge fund, Long Term Capital Management, over extended itself throughout the entire world leading up to the Asian Currency Crisis that precipitated the 1998 Russian Default. The fourth was in 2008 when the world financial system ground to a halt in the wake of the subprime mortgage Crisis caused by American financial institutions over extending themselves all over the world in marketing securities backed by fraudulently obtained sub-prime mortgages.

All of these crises led to economic catastrophes—for the Latin American countries during the Latin American Debt Crisis in the 1980s, for Mexico following the Mexican Peso Crisis in 1994, for the South and East Asian countries and Russia following the 1998 Asian Currency Crisis and Russian Default, and for most of the world following the worldwide financial crisis created by the subprime mortgage fraud that came to a head in 2008. These crises were preceded by huge paper profits for the institutions that fostered the speculative bubbles that led to these crises as well as huge salaries and bonuses for the managers and owners of these institutions. Those who were able to take advantage of these catastrophes made fortunes while most everyone else was left holding the bag. This is especially so for those who rely on wages and salaries for their livelihood, who are forced to live with the uncertainty and economic losses caused by these catastrophes, and whose taxes must pay for the economic bailouts that resulted. (Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

In addition to creating a cycle of international crises, the officials in charge of our government have allowed the American dollar to be overvalued in international markets for much of the past thirty-five years. This act of malfeasance, misfeasance, or just plain incompetence has been so devastating to our economic system that it will take decades, if not generations, to repair the damage. (Phillips Eichengreen)

The Overvalued Dollar and International Trade

In theory, the interaction of supply and demand in the markets for international exchange is supposed to yield an optimal allocation of international investment, production, and consumption, but this theory ignores the casino like nature of the foreign exchange markets and the ability of a country to undervalue its currency relative to the currencies of other countries if left unchallenged to do so. (Bergsten) This leads to a deficit in the balance of trade in those countries with overvalued currencies—that is, the value of their domestically produced goods and services sold to foreigners (exports) is less than the value of foreign produced goods and services purchased domestically (imports). In the real world, a persistent deficit in a country's balance of trade can have devastating consequences. (Autor)

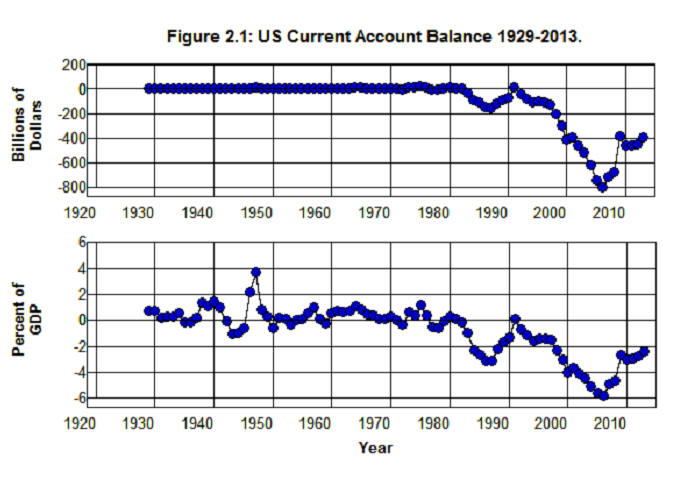

The extent to which our trade policies have allowed this to happen is indicated in Figure 2.1, which shows our international Current Account Balance from 1929 through 2013, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP. The current account balance is determined primarily by the difference between the value of our exports and the value of our imports. It also includes net foreign transfers and the difference between income earned by Americans on foreign investments and income earned on domestic investments by foreigners, though, as is shown in the Appendix at the end of this chapter, these components of the Current Account Balance are generally quite small compared to the values of exports and imports.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2013 (B103PDF|XLS), Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.2.5).

The graphs in this figure clearly show the consequences of our international policies as we went from a relatively stable balance through 1980 to a $160 billion deficit in 1987 that amounted to 3.4% of GDP. This balance gradually adjusted through 1991 then fell precipitously to reach a record deficit of $804 billion in 2006, a deficit equal to 6.0% of GDP.

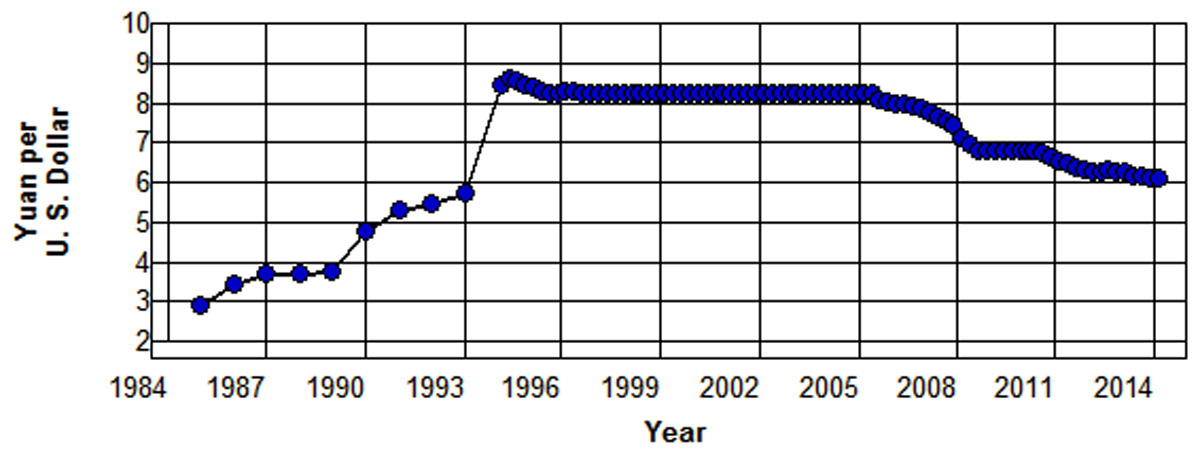

International exchange rates are supposed to adjust to eliminate this kind of imbalance, as they seemed to have done in 1991, but, as was noted above, this will occur only if a country is not allowed to undervalue its currency in world markets over time. Figure 2.2 shows the Chinese yuan/dollar exchange rate from 1988 through the first quarter of 2014. Here is a classic example of how unregulated foreign exchange markets can fail to adjust as they are supposed to. Even though our trade deficit with China grew from $68.8 billion in 1999 to $372.7 billion through 2005, there was no change in the yuan/dollar exchange rate in spite of this increase.

Figure 2.2: Chinese Yuan/U.S. Dollar Exchange Rate, 1985-2014.

Source: Economic Report of the President: 2006 (B110PDF|XLS) OANDA.

It is worth emphasizing at this point that, even though our trade deficit with China is three times that of our deficit with the rest of Asia, all of Europe, or with Latin America, the problem is not just with the yuan/dollar exchange rate. As should be clear from Figure 2.3, the entire structure of U.S. exchange rates is overvalued today. The table in this figure shows the U.S. balance of trade with its major trading partners and with the major trading areas of the world from 2004 through the third quarter of 2012. A clear indication of the degree to which the entire structure of U.S. exchange rates is too high is given by the fact that the only countries in this table with which the United States has not had a consistent negative balance over this nine years are Singapore and Brazil.

Figure 2.3: US International Trade Balance by Country and Area, 2004-2012.

Source: Economic Report of the President, 2013 (B105PDF-XLS).

Undoubtedly, some of the deficits exhibited in this table can be explained by the growing need for U.S. dollars as international reserves held by foreign countries, but certainly not all. This situation is unsustainable, and the exchange markets will eventually adjust to correct this imbalance. But when this kind of imbalance is allowed to persist for any length of time, the eventual adjustment has the potential to precipitate an economic crisis—a crisis that could have been avoided had this kind of imbalance not been allowed to occur in the first place. (Stiglitz Galbraith Reinhart Eichengreen Rodrik Bergsten)

Even more important is the fact that the persistence of this kind of imbalance has destructive effects on our economy. The result of the unfair competition created by the overvalued U.S. dollar has been the destruction of entire industries in the United States as much of the manufacturing sector of our economy has been outsourced to foreign lands. Particularly hard hit in this regard are the computer and consumer electronics industries. Equally disturbing is the fact that the technologies necessary to produce these goods have been shipped abroad as well. These technologies are essential to the increases in productivity necessary to improving our economic well-being, but once the industries that embody these technologies are gone, they may be gone for a very long time. Even if the value of the dollar were to fall in the near future, it would take years to reconstitute many of these industries and to embed in the American economy the requisite capital and technologies needed to produce these goods. (Phillips Eichengreen Rodrik Palley)

The Overvalued Dollar and International Debt

The trade deficits caused by an overvalued dollar have another disturbing consequence. When we have a deficit in our balance of trade, the demand for dollars to finance our exports in the market for international exchange is less than the supply of dollars made available in these markets through the purchase of our imports. This difference shows up as a deficit in our current account. When such a deficit exists, foreigners accumulate more dollars through the sale of their exports than they need (at the existing exchange rates) to purchase the imports they are willing to purchase from us. At this point, foreigners have a choice: They can either refuse to accept more dollars at the existing exchange rates and, thereby, force our exchange rates down—thus stimulating our exports and inhibiting our imports until a current account balance is obtained at a lower exchange rate—or they can use the excess dollars they are accumulating to purchase assets from Americans in the international capital market. The assets purchased in this market are essentially any asset an American is willing to sell for dollars but primarily consist of financial assets such as government and corporate securities.

Our balance in the international capital market is referred to as our capital account balance, and this balance must, by definition, exactly offset our current account balance—that is, a deficit in our current account must, by definition, be offset by a surplus in our capital account that is exactly equal to the deficit in our current account. (Ott B103 PDF-XLS)

When foreigners buy American assets in the international capital market, they are, in effect, investing in the United States. At the same time, to the extent these assets are government and corporate bonds, they are lending us money. To the extent these assets are not government and corporate bonds they must be corporate stocks, American businesses, real estate, or other assets in the United States. This means that the greater our current account deficit, the greater our capital account surplus, and, as a result, the current account deficits displayed in Figure 2.1 indicate the rate at which we are driving ourselves into debt to foreigners or selling our assets off to foreigners.

Figure 2.4 shows the Net International Investment Position of the United States from 1976 through 2013, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP. Our Net International Investment Position is the difference between the value of the assets Americans own in foreign lands and the value of the assets foreigners own in the United States. This graph shows how the surpluses in our capital account that correspond to the deficits in our current account have accumulated since 1976. The extent to which this difference is made up of debt obligations—mostly corporate and government bonds—represents the net debt Americans owe to foreigners. The extent to which this difference is not made up of debt obligations it represents the sale to foreigners of corporate stocks, American businesses, real estate, or other assets in the United States.

Figure 2.4: Net International Investment Position

of the US, 1976-2013.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.2.5). (1)

It is clear from this figure that there has been a fundamental change in our indebtedness and the sale of our asset to foreigners as a result of our free-market international finance and trade policies. Since 1976, our Net International Investment Position has gone from a positive $163 billion (8.9% of our GDP) to a negative $4.6 trillion by 2013 (26.0% of our GDP).

At the end of World War II the United States was the largest creditor nation in the world. As a result of the overvaluation of the dollar, this ended in 1985 when we became a net debtor to the rest of the world. As a result of our trade policies we have increased our net debt and sold off American assets to foreigners to the tune of some $4.6 trillion since 1984, and, in the process, we went from being the world's largest creditor nation to the world's largest debtor nation. (BEA IMF)

Why Foreign Debt Matters

For a country to accumulate foreign debt as it runs a trade deficit is not, in itself, a bad thing. The United States followed this course throughout much of the nineteenth century. But throughout that period we used that debt to import capital goods and foreign technology. We invested in public education and other public infrastructure that led to tremendous increases in productivity in agriculture and manufacturing. We built canals, national railroad and telegraph systems and created steel, oil, gas, electrical, automobile, and aviation industries. Our trade policies protected our manufacturing industries as our economy grew more rapidly than our foreign debt, and as Europe squandered its resources in senseless conflicts, by the end of World War I the United States had become a net creditor nation and the economic powerhouse of the world.

This is not the course we have followed over the past forty years. We have exported rather than imported capital goods and technology, and, in return, we borrowed to import consumer goods. We invested less rather than more in our public education, transportation, and other public infrastructure systems than other countries have invested. While we made huge advances in the electronics and computer industries over the last forty years, our trade policies have not protected our manufacturing industries, and we have outsourced the manufacturing and technological components of these industries to foreign lands. As a result, our economy is not growing more rapidly than our foreign debt, and it is the United States that is squandering its resources in senseless conflicts.

The process of rising trade deficits can sustain itself only so long as foreigners are willing to lend us the dollars or buy up American assets to finance these deficits and only so long as Americans are willing to tolerate this situation. This situation is unsustainable, and when foreigners refuse to continue to do so or the American public is no longer willing to tolerate this situation—as eventually must come to pass as foreign debt continues to increase relative to GDP—the existence of this debt makes us vulnerable to the same kinds of international financial crises faced by other countries that have found themselves in a similar situation.. (Eichengreen Rodrik Galbraith Reinhart Philips Stiglitz Kindleberger Morris Klein)

The dramatic redistribution of income within our society, the breakdown of the fiduciary structure in our economic and political systems, the increasing prevalence and severity of financial and economic instability in the wake of speculative bubbles, and the dramatic deterioration of our net international investment position are all either a direct or indirect result of the economic policy changes that have occurred over the past forty years. All of these phenomena are interrelated, and, as we will see in the next chapter, they are also interrelated with another phenomenon we have experienced in the wake of these policy changes—namely, the dramatic increase in domestic debt.

Appendix on International Exchange

Exchange Rates and International Trade

The exchange rate between the American dollar and a foreign country's currency is nothing more than the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars. If the Chinese must pay ¥10 to purchase one dollar of our currency, the YUAN/USD exchange rate will be ¥10 per dollar. Similarly, if the EURO/USD exchange rate is €0.75 per dollar that means that Europeans must pay €0.75 to purchase one dollar of our currency. In general, the higher our exchange rate the higher the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars; the lower our exchange rate the lower the price foreigners must pay in their currencies to purchase dollars.

This works in reverse, of course, when it comes to us buying foreign currencies. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar then we can purchase ¥10 for one dollar, which works out to a price of $0.10 per yuan. If the exchange rate is ¥5 per dollar we can only purchase ¥5 for one dollar, which works out to a price of $0.20 per yuan. In general, the higher our exchange rate the lower the price we must pay in our currency for a foreign currency; the lower our exchange rate the higher the price we must pay in our currency for a foreign currency.

Exchange rates are extremely important in determining the flow of international trade because, in general, the producers of goods in foreign countries must pay their costs of production (employees, suppliers, etc.) in their domestic currencies. Those costs, in turn, determine the prices in terms of their domestic currencies at which they are willing to sell the goods they produce. If we wish to purchase goods from a foreign country we must pay the prices in terms of their domestic currencies at which producers are willing to sell. Similarly, if foreigners wish to purchase goods from us they must pay the prices in terms of the American dollar at witch American producers are willing to sell. As a result, the exchange rates between currencies determine the prices people must pay in their own currencies for the goods they import from other countries.

To see how this works, consider a bushel of wheat that a Chinese producer is willing to sell for ¥20. If the YUAN/USD exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar, someone in the United States who wished to purchase that bushel of wheat has to come up with $2 to purchase the ¥20 necessary to pay the Chinese producer ¥20. The dollar price of that bushel of Chinese wheat in this situation will be $2/bu. If, instead, the exchange rate is only ¥5 per dollar, the American purchaser has to come up with $4 to purchase the ¥20 needed to purchase that bushel of Chinese wheat. This means the dollar price of that bushel of Chinese wheat will increase to $4/bu. even though the yuan price of wheat in China hasn't changed. In general, the higher our exchange rates the lower the prices in dollars we must pay for foreign goods; the lower our exchange rates the higher the prices in dollars we must pay for foreign goods.

Again, this works in reverse when it comes to the Chinese buying from us. If the price of a bushel of wheat in the United States is $3, and our exchange rate with China is ¥10 per dollar, someone in China who wishes to purchase a bushel of American wheat will have to come up with ¥30 to purchase the $3 needed to pay the American price of wheat, and the yuan price of American wheat will be ¥30/bu. But if our exchange rate falls to ¥5 per dollar the Chinese importer will have to come up with only ¥15 to purchase the $3 needed to purchase the American wheat, and the yuan price of American wheat will fall to ¥15/bu. even though the dollar price of wheat in the United States hasn't changed. In general, the higher our exchange rates the higher the prices foreigners must pay in their currencies for our goods; the lower our exchange rates the lower the prices foreigners must pay in their currencies for our goods.

The point is, exchange rates play a crucial role in determining whether or not it is profitable for us to import goods from foreign countries or foreigners to purchase the goods we export: At a given set of foreign and domestic prices, when our exchange rates go up, the dollar prices of goods produced in foreign countries go down, and it becomes more profitable for us to import foreign goods; when our exchange rates go down, the dollar prices of goods produce in foreign countries go up, and it becomes less profitable for us to import foreign goods. At the same time, when our exchange rates go up, the foreign currency prices of our goods go up, and it becomes less profitable for foreigners to purchase our exports; when our exchange rates go down, the foreign currency prices of our goods go down, and it becomes more profitable for foreigners to purchase our exports.

Exchange Rates, Wages, and International Trade

The wage rate is nothing more than the price of labor. As a result, exchange rates determine the dollar price of labor (wages) in different countries in the same way they determine the dollar price of any other foreign good. If the price of labor is ¥40/hr. in China and the exchange rate is ¥10 per dollar, it will cost us $4 to purchase the ¥40 that an hour of labor costs in China. This means that the dollar price of Chinese labor will be $4/hr. If the exchange rate is ¥5 per dollar, it will cost us $8 to purchase the ¥40 that an hour of labor costs in China, and the dollar price of Chinese labor will be $8/hr. Thus, an increase in the exchange rate will decrease the price of foreign labor in terms of dollars, just as it will decrease any other foreign price in terms of dollars, and a fall in the exchange rate will increase the price of foreign labor in terms of dollars, just as it will increase any other foreign price in terms of dollars.

This brings us to a very important point, namely, that just because the exchange rate is such that the price of labor is lower in a given country (such as China) when measured in the same currency (either yuans or dollars) than it is in the United States, this does not mean that everything will be cheaper to produce in that country than in the United States. The reason is that the price of labor is only one of the factors that determine the cost of producing something. There are other costs as well, in particular, the costs of natural resources such as land and of capital. In addition, the cost of labor does not depend solely on the price of labor. It also depends on the productivity of labor, that is, on the amount of output that can be produced per hour of labor employed.

The importance of this should become clear when we consider that, in spite of the fact wages are much lower in China than they are in the United States, we do not import wheat from China. The reason is that, in general, capital equipment is scarce and very expensive in China relative to labor, especially the kinds of farm equipment we take for granted in the United States. The scarcity of capital equipment, in turn, means that much of the work that is done by farm equipment in the United States must be done by people in China to the effect that more labor is required to produce a given quantity of wheat in China than is required to produce the same quantity of wheat in the United States.

The fact that it takes more labor to produce a given quantity of wheat in China than it does in the United States means that the dollar cost of labor in producing wheat in China is higher than the dollar price of labor indicates. In fact, when we combined the cost of labor in China (i.e., the price of labor times the quantity of labor that must be employed to produce a given amount of wheat) with all of the other costs of producing wheat—including the cost of farm equipment, land, transportation, energy, taxes, etc.—we find that, given the exchange rate between the yuan and the dollar, it actually costs more to increase the production of domestically produced wheat in China than it does to purchase wheat from the United States. As a result, we do not import wheat from China. Instead, China imports wheat from us. (Coia USDA) This is so even though the dollar price of Chinese labor is far below the dollar price of American labor.

It is the cost of increasing the production of domestically produced goods relative to the cost (measured in the same currency) of purchasing from a foreign country that determine which goods we import from foreign countries and which goods foreign countries import from us, not the relative prices of labor. And the fact that these relative costs are determined by exchange rates means that in order to understand how imports and exports are determined, we must look at how exchange rates between countries are determined as well as how costs within countries are determined. (Smith)

Exchange Rates and International Capital Flows

Since the producers of the goods must be paid in their domestic currencies, a country’s imports must be financed in the foreign exchange market, that is, in the market in which the currencies of various countries are bought and sold. The most important source of demand in this market comes from foreigners who purchase the foreign exchange needed to purchase the country's exports. Similarly, the most important source of supply comes from a country's importers who sell the country's currency in order to obtain the foreign exchange needed to purchase the country’s imports.

When the value of a country's imports is equal to the value of its exports, the supply of foreign exchange from those who purchase the country’s exports will equal the demand for foreign exchange by those who purchase the countries imports, and the country will be able to obtain enough foreign exchange in the foreign exchange market to finance its imports from the sale of its exports. But if the value of a country’s imports exceeds the value of its exports there will be a deficit in its balance of trade, and it will not be able to finance all of its imports in this way. This deficit must be financed, and one of the ways it can be financed is from the incomes earned by individuals and institutions within the country on the investments they have made in foreign countries.

When individuals or institutions in one country own earning assets (investments) that are denominated in other countries' currencies, the earnings on those assets can only be spent in the domestic economy if they are converted into the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market. As they are converted, they contribute to the demand of the country’s currency in the foreign exchange market. By the same token, when individuals or institutions in other countries own earning assets that are denominated in the domestic currency, the earnings on those assets can only be spent in the foreign countries if they are converted into the foreign countries’ currencies in the foreign exchange market. As they are converted, they contribute to the supply of the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market.

A similar situation exists when individuals or institutions simply transfer funds abroad. When an individual sends money to a family member abroad, a business transfers funds to a foreign subsidiary, or a government provides aid to a foreign country in the form of cash it increases the supply of the domestic currency in the foreign exchange market as those funds are converted into foreign currencies by their recipients. As a result, these kinds of international transfers of funds contribute to the supply and demand for a country’s currency in the foreign exchange market in the same way international payments of income contribute to the supply and demand for a country’s currency in this market.

A country’s net exports—that is, the difference between the value of its exports and the value of its imports—plus its net income (similarly defined) on foreign investments plus its net transfers of funds is referred to as the country's current account balance. The significance of this balance is that it defines the extent to which a country is able to pay for its current imports, the current income earned by foreigners who hold earning assets denominated in the country's currency, and its current transfers of funds abroad out of the foreign exchange it receives from the sale of its current exports, the current income it receives from its holdings of earning assets denominated in foreign currencies, and its receipts from current transfers of funds by foreigners.

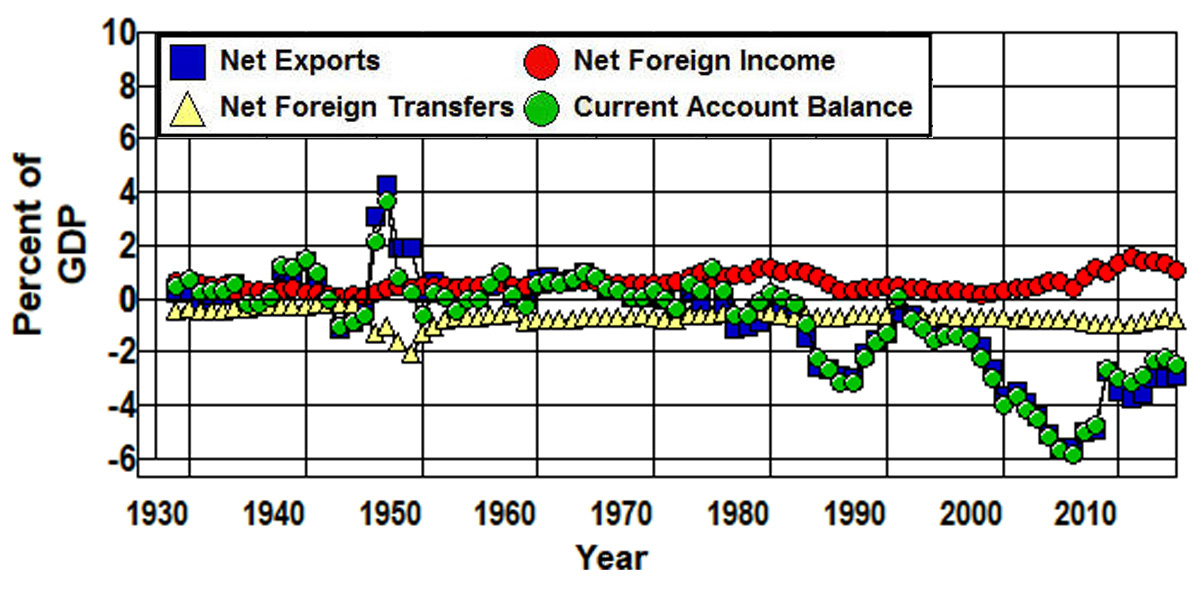

The composition of the current account balance for the United Sates from 1929 through 2013 is shown in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5: U.S. Current Account Balance, 1929-2015.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (4.1)

The extent to which our Current Account Balance has been dominated by our balance of trade (Net Exports) is clear in this figure in that, in most years, these two variables are barely distinguishable in Figure 2.5.

When a country's current account is balanced, all of its current international expenditures can be financed by its current international receipts of foreign exchange, where its current expenditures and receipts are those that are generated through the ordinary process of producing goods, earning income, and transferring income in the international economic system. When there is a deficit in a country's current account, all of the country's current international expenditures cannot be financed through its current receipts. Similarly, when there is a surplus in a country's current account the country receives more than enough foreign exchange from its current receipts to finance its current international expenditures.

By definition, one country's current account deficit is some other country's current account surplus. Countries with current account deficits must finance those deficits in their current account obligations. Since current account deficits cannot be financed through the ordinary process of producing goods, earning income, and international transfers the only way they can be financed is through a transfer of assets from surplus countries to deficit countries. These asset transfers are referred to as international capital flows, and they represent a willingness of foreigners in surplus countries to invest in deficit countries—either directly by purchasing real assets in the country or indirectly by purchasing the country's financial obligations, usually bonds or other forms of debt. Foreign investments of this sort can be used to finance a deficit in a country's current account because the sellers of these assets must be paid in the deficit country's currency just as the producers of a country's exports must be paid in the producers’ domestic currencies.

If a country cannot finance its current account deficit through a capital account surplus it means that the demand for its currency in the market for foreign exchange is less than the supply of its currency in this market. In this situation, either its exchange rates must fall (which will make its exports less expensive to foreigners and its imports more expensive in its domestic markets and, thereby, reduce the current/ capital account deficit/surplus) or the expected rates of return on foreign investment in that country must increase (which will make foreign investment in the country more attractive and, thereby, increase the willingness of foreigners to finance the current/capital account deficit/surplus by purchasing its assets) until the demand and supply for its currency is brought into balance in the market for foreign exchange.

Instability in Unregulated International Markets

As is explained in the text, a deficit in a country's balance of trade or in its current account is not, in itself, a bad thing, but there are two situations in which it can become a problem. The first arises from the fact that while decisions regarding current account transactions (imports, exports, and transfers) tend to progress relatively slowly over time, the purchase and sale of financial assets in international markets can be executed almost instantly. As was discussed at the beginning of this chapter, this can lead to serious instability in the markets for foreign exchange as speculation and the concomitant speculative bubbles that culminate in financial panics and economic crises are accompanied by, and are often the result of, dramatic and sudden shifts in international capital flows. (EPE Stiglitz Klein Johnson Crotty Bhagwati Philips Galbraith Morris Reinhart Kindleberger Smith Eichengreen Rodrik)

The second situation in which a deficit in a country’s balance of trade or in its current account can become a problem has to do with the way in which foreign investments can be used to manipulate exchange rates. If a country with a current account surplus is willing to make foreign investments it can accumulate assets in deficit countries and, thereby, prevent its exchange rates from rising (deficit countries' exchange rates from falling). This makes it possible for the surplus country to keep the demand for its exports from falling in response to its surplus. The risk in doing this is that, because the assets being accumulated are denominated in foreign currencies, those who accumulate foreign assets in this way will take a capital loss on those assets in terms of their own currency if and when its exchange rates eventually rises (foreign rates fall) since the assets will then be worth less in terms of the domestic currency of the surplus country.

It is worth noting, however, that this potential for capital loss is not necessarily a deterrent to a country artificially suppressing its exchange rate in this way. To the extent the accumulated foreign assets can be transferred to the country's central bank or to its government, it is the central bank or government that will take the capital loss when exchange rates eventually adjust rather than those who earn their incomes in the exporting industries or otherwise benefit from the lower exchange rate.

In addition, as will be explained in Chapter 3, a trade surplus makes it possible for the distribution of income to be concentrated at the top of the income distribution in that, given the state of technology, when a country has a surplus in its balance of trade, full employment can be maintained with a higher concentration of income than in the absence of a trade surplus. It is also worth noting that, as is apparent from Figure 2.3 above, almost all countries have been willing to take this risk vis-à-vis the American dollar in recent years in order to build up their international reserves, stimulate their economies, or maintain the concentration of income within their societies.

Allowing countries to prevent their exchange rates from rising and, thereby, keeping our exchange rates from falling has led to our exchange rates being overvalued in the market for foreign exchange for most of the past thirty-five years as foreign countries have accumulated surpluses in their balance of trade while we have accumulated deficits in ours. As a result, foreign goods have been undervalued in our domestic markets for most of that period which has given importers an unfair, competitive advantage in these markets. This has placed a serious drag on the American economy and has had a particularly a devastating effect on our manufacturing industries. In addition, as we will see in Chapter 3 through Chapter 10, to the extent this drag has contributed to the need for a rising debt to maintain employment, it has also contributed to the instability of the American economy.

See the Appendix on International Exchange at the end of this chapter for an explanation of what it means for the dollar to be under/overvalued and how the markets for international exchange determine exchange rates, international trade, and international capital flows.

Since returning to a fixed exchange rate system is neither a feasible nor a desirable option for the United States today, the deficiencies of this type of system are not discussed in this eBook. For an explanation of these deficiencies see a Brief History of the Gold Standard in the United States, Krugman, and Krugman. For a more in depth treatment see: Skidelsky, Eichengreen, Rodrik, and Kindleberger. For an explanation on how a floating (flexible) exchange rate system works see the Appendix on International Exchange at the end of this chapter.

;10 That is, to the extent this deficit is not offset by net foreign income/transfers. See the Appendix on International Exchange at the end of this chapter.

See the Appendix on Foreign Exchange at the end of this chapter for a discussion of how this kind of vulnerability arises.

[12 If it didn’t cost more to increase the amount of domestically produced wheat in China than it costs to purchase wheat from us at the existing exchange rate, the Chinese could save money by increasing the production of domestically produced wheat and cutting back on the amount of wheat they purchase from us. This would give Chinese farmers an incentive to increase the production of domestically produced wheat until it did cost more to increase production at home than to purchase from us.

Since the U.S. dollar is generally used as an international reserve currency by most countries, U.S. dollars are the actual medium of exchange that is used in most international transactions. Thus, importers generally convert their currencies into dollars in order to pay in dollars and exporters generally accept dollars in payment. Ultimately, the dollars accepted by exporters must then be converted to the exporter’s domestic currency if they are to be spent in the exporter’s domestic economy, or, as will be discussed below, converted into some other currency if they are not used to purchase dollar denominated assets. It is this conversion process of foreign currencies into and out of dollars that takes place in the market for international exchange. See Eichengreen for a discussion of the role played by the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency in the market for international exchange.