Chapter 4: Going Into Debt

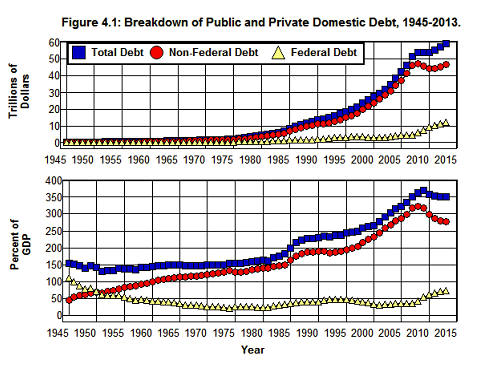

Figure 4.1 shows a breakdown of the public and private domestic debt in the United States from 1945 through 2013, both in absolute dollars and as a percent of GDP.

Source: Federal Reserve (L1), Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.1.5).

As is shown in this figure, Total Debt increased from less than $500 billion in 1950 to $59 trillion by 2013 and, in the process, increased from 142% to 351% of GDP. It can also be seen that Federal Debt decreased rather consistently relative to GDP through the mid 1970s, and even though Federal Debt increased considerably after 1980 (from $735 billion and 26% of GDP in 1980 to $12.3 trillion and 74% of GDP by 2013) Federal Debt played a relatively minor role in the increase in the total. The major source of the increase in total debt following 1980 was in the non-federal sector of the economy.

The pattern of Non-Federal Debt increases displayed in Figure 4.1 is particularly telling. This debt increased from $1.3 trillion in 1970 to $47.2 trillion in 2008 and, in the process, increased from 121% of GDP to 321%. This increase was gradual until 1981 and then went from $4.4 trillion and 138% of GDP to $11.3 trillion and 189% in just 9 years. It dipped slightly relative to GDP in 1992 then increase dramatically over the next 14 years.

It is no accident that the dramatic jump in Non-Federal Debt from 1983 through 1990 followed on the heels of the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 and Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982. As was noted in Chapter 1, it was the deregulatory provisions in these two acts that led to junk bond and commercial real estate bubbles in the 1980s and the first major financial crisis in the United States since the Crash of 1929. It is also no accident that the explosion of debt came to an end in 1990 on the heels of the Savings and Loan Crisis or that Non-Federal Debt began to rise again in the mid 1990s.

Debt and Deregulation

The Savings and Loan Crisis marked a minor setback in the movement to deregulate the financial sector. Congress passed seven major pieces of legislation to reregulate the financial sector in response to this crisis. The first was the Competitive Equality Banking Act in 1987 to recapitalize the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) which was bankrupted by the crisis, and to strengthen the supervision in the savings and loan industry. Two years later Congress passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act which transferred savings and loan deposit insurance from the failed FSLIC to the FDIC, reorganized and further strengthened the supervisory structure of the savings and loan industry, and created and funded the Resolution Trust Corporation to deal with the savings and loan institutions that had failed. (FDIC)

Next came the Comprehensive Thrift and Bank Fraud Prosecution and Taxpayer Recovery Act of 1990 to deal with the abusive practices of the new breed of savings and loan owners/managers, and in 1991 the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (FDICIA) was passed. This act greatly increased the powers of the FDIC, put forth new capital requirements for depository institutions, created new regulatory and supervisory examination standards, and established prompt corrective action standards that ostensibly took away some of the discretion of regulators when it came to dealing with insolvent institutions.

Finally, Congress passed the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 which dealt with abuses in the home mortgage market and gave the Federal Reserve the power to regulate this market.

These acts, combined with the enhanced vigilance on the part of regulators brought on by the Savings and Loan Crisis, put an end to the explosion of domestic debt that accompanied the financial deregulation of the early 1980s. Unfortunately, this setback to the deregulatory movement was only temporary. As the Savings and Loan Crisis unfolded, the general public failed to appreciate the seriousness of the situation since the consequences of the crisis seemed to be relatively minor. There was a minor recession in 1990 that lasted into 1991, and the crisis cost the taxpayers some $130 billion, but there was no sense of panic at the near meltdown of the financial system. Federal deposit insurance prevented a run on the system, and the lives of relatively few people were seriously disrupted. At the same time, as was noted in Chapter 1, a relatively large number of people made personal fortunes out of this crisis. Since there was very little public outcry, very few lessons were learned, and there were no political consequences for those who brought this crisis about.

Its mantra of lower taxes, less government, and deregulation carried the Republican Party to victory in the 1988 presidential election in spite of the savings and loan debacle, and the successes of the Republican Party throughout the 1980s had a profound effect on the leadership of the Democratic Party. A significant number of Democrats who opposed the free-market economic policies advocated by the Republicans either retired or were defeated at the polls. As a result, many Democrats began to embrace these policies—either out of conviction or to enhance their political survival. As the electorate shifted to the right on economic issues, the Democratic Party shifted to the right on these issues as well, and by the time of the 1992 election, opposition to financial deregulation was muted. (Cowie)

Bill Clinton held himself out as a "New Democrat" who embraced "values that were both liberal and conservative." He promised to reinvent "government, away from the top-down bureaucracy of the industrial era, to a leaner, more flexible, more innovative model appropriate for the modern global economy." (DLC) When he became president he invited a number of ideologically minded economists to join his administration, three of whom came to the fore: Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin, and Lawrence Summers. (Turgeon)

Alan Greenspan was appointed by Reagan to chair the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and was reappointed to this position twice by Clinton. Robert Rubin was co-chairman of Goldman Sachs before Clinton selected him to chair the National Economic Council and then appointed him to replace Lloyd Benson as Secretary of Treasury. Lawrence Summers worked as an economist in the Reagan White House before he joined the Clinton administration, first as Treasury Undersecretary for International Affairs and then as a replacement for Rubin as Secretary of Treasury. This is the triumvirate that dominated economic policy deliberations in the Clinton administration—the group Time Magazine dubbed “The Committee to Save the World.” (Ramo Frontline)

There was little hope for financial regulation from this group. While the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act was passed in 1994, its provisions giving the Federal Reserve responsibility for regulating the mortgage market were ignored by Greenspan, and the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act was passed that same year allowing interstate banking throughout the United States. Passage of this bill was particularly ominous in light of the fact that the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 and Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914—enacted to protect the public from anticompetitive practices on the part of businesses—had been virtually ignored since the Reagan Revolution began in 1980.

The spirit of deregulation got a further boost from the 1994 election. When the dust settled from that election Republicans had control of both the House and the Senate for the first time since 1954, and it was clear that the movement to reregulate the financial system was dead. A seemingly blind, ideological faith in Free-Market Capitalism and deregulation became the tenor of the times. The extent to which this was so was made clear by Clinton in his 1996 State of the Union Address when he announced to the world that "the era of big government is over" and took pride in the fact that his administration had eliminated "16,000 pages of unnecessary rules and regulations."

On November 4, 1999, Congress passed the Financial Services Modernization Act (FSMA) which was signed into law by President Clinton on November 12. As has been noted, this act repealed those provisions in the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 that prevented commercial bank holding companies from becoming conglomerates that are able to provide both commercial and investment banking services as well as insurance and brokerage services. Congress then passed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) on December 14, 2000 which Clinton signed into law on December 21. This act explicitly prevented both the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and state gambling regulators from regulating the derivatives markets.

While the laws passed in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to stronger regulation of depository institutions, such as commercial and savings banks and savings and loans, by the mid 1990s the antiregulatory atmosphere in Washington made the enforcement of the new laws problematic, and, as we will see in Chapter 8, passage of the FSMA and CFMA in 1999 and 2000 gave a free hand to investment banks, bank holding companies, hedge funds, and special purpose vehicles in the markets for repurchase agreements and financial derivatives.

The story of this era is reflected in Figure 4.1 which shows 1) the dramatic increase in Non-Federal debt as a percent of GDP following the deregulation of depository institutions and lax supervision on the part of regulators in the early 1980s, 2) the leveling off and slight fall in this debt as a percent of GDP in response to the reregulation of depository institutions and greater vigilance on the part of regulators in the late 1980s and early1990s, 3) the beginning of the increase in this debt in the mid 1990s as the regulatory attitude in Washington changed, and 4) the continuing increase in this debt ratio from 2000 through 2008 following the passage of FSMA and CFMA.

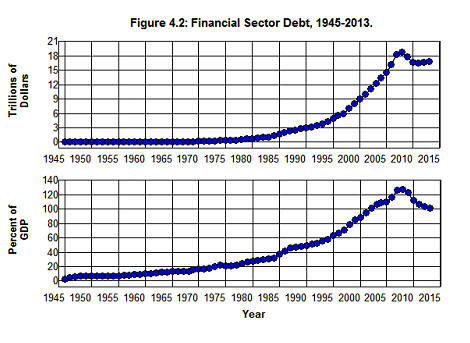

This same story is told in Figure 4.2 which shows the expansion of debt on the part of financial institutions over this same period.

Source: Federal Reserve (L1), Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.1.5).

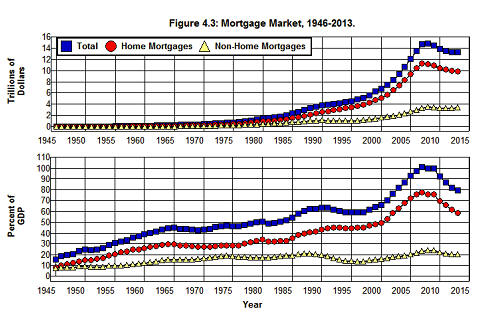

Figure 4.3 shows what happened in the mortgage markets following the deregulation of the financial system in the 1980s.

Source: Federal Reserve (L.217), Bureau of Economic Analysis (1.1.5).

The increase in Non-Home Mortgages as a percent of GDP fueled by the speculative bubble in the commercial real-estate markets of the 1980s can be seen in this figure, as can the fall in this market following the bursting of this bubble. The increase in Non-Home Mortgages that accompanied the speculative bubble in the housing market during the early to mid 2000s can also be seen in this figure, as is the collapse of this market following the Crash of 2008.

Figure 4.3 also shows the dramatic increase in Home Mortgages as a percent of GDP that took place during the commercial real-estate bubble in the 1980s and the huge increase that fueled the housing bubble in the 2000s along with the collapse of this market following 2007.

What Financial Institutions Do

It should not be surprising that the behavior of debt within society is related to the degree of regulation in the financial system. Creating debt is what financial institutions do! They provide the mechanisms by which borrowing and lending take place within the economic system. In the process they provide other services such as insurance, a safe and convenient place to keep money, pension plans, and brokerage and underwriting services. They also deal in equities, that is, stocks as opposed to loans, bonds, mortgages, and other types of debt instruments. They underwrite the sale of newly issued equities and broker the purchase and sale of previously issued equities. They may also invest in equities, but the main business of finance is debt, not equities. Debt is where the money is. Without debt, there would be no financial system as we know it.

The primary mechanism by which financial institutions create debt is through the process of intermediation which means they intermediate between the ultimate borrowers and lenders in society. They take in money from the individuals and businesses that are the ultimate lenders in society and lend the money to individuals and businesses that are the ultimate borrowers. Banks take in money from their depositors (the ultimate lenders) and relend the money in the markets for consumer and business loans (the ultimate borrowers). Insurance companies take in money from their policy holders (the ultimate lenders) and relend the money in the mortgage and bond markets (the ultimate borrowers). Pension funds take in money from employees (the ultimate lenders) and lend the money in the mortgage and bond markets as well (the ultimate borrowers).

In addition, financial institutions (primarily banks but, as we will see in Chapter 7, shadow banks as well) have the power to create debt out of thin air as a portion of the money they lend is lent back to them to be relent again.

The process of financial intermediation is an essential part of the economic system, and without it the economic system cannot function, but unless this process is strictly regulated and supervised by the government, it is highly unstable. The reason for this is obvious: Financial institutions lend other peoples’ money. They take money from one group of people and lend it to another group of people as they take a cut in the process. Not only does this provide innumerable opportunities for fraud to flourish on a grand scale, there are powerful forces within society that drive the system of financial intermediation to fund speculative bubbles that increase debt beyond any possibility of repayment. The reason for this is also obvious: The more money financial institutions are able to lend, the greater their cut, and the more money they are able to make. In addition, those in the financial system who handle other peoples’ money have access to information that provides opportunities to profit from speculative bubbles in ways that are not available to those outside the system. (Stewart WSFC)

The simple fact is this: huge fortunes can be made by those who are able to take advantage of speculative bubbles. This was pointed out in Chapter 1 with regard to 1) the increase in the income share of the top 1% of the income distribution associated with the various speculative bubbles we have experienced since the 1920s, 2) the increase in the amount of income received in the form of capital gains as a percent of total income associated with these bubbles, and 3) the $700 billion dollars in additional profits from 2001 through 2007 that financial institutions received as a result of the housing bubble. It is no mystery why speculative bubbles persist in the face of such massive gains by those who are able to take advantage of these bubbles. The problem is, of course, that when those in charge of our financial institutions are allowed to finance speculative bubbles and increase debt beyond any possibility of repayment, they do not place only their own money and economic wellbeing at risk. They place other peoples' money and economic wellbeing at risk as well, and they threaten to bring down the entire economic system.

There are a host of powerful arguments, based on seemingly sound economic theory and irrefutable logic, put forth by those who favor deregulating markets to explain why unregulated financial markets lead to economic efficiency, growth, and prosperity, and why government regulation is the source of all problems, (Fox Taleb Dowd) but we are not talking about theory or logic here. We are talking about cold hard historical fact that goes far beyond what happened in the Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980s, the dotcom and telecom bubbles of the 1990s, and the housing bubble and Sub-Prime mortgage fraud of the early 2000s. We are talking about the economic catastrophes brought on by the financial crises in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1907, and we are talking about the last time this happened in the United States—1929. (Fisher Keynes Polanyi Kindleberger Minsky Phillips Morris Dowd Reinhart Johnson Skidelsky Kindleberger Kennedy MacKay Graeber Galbraith White)

The Crash of 1929 brought an end to the roaring twenties with a vengeance, and the experience of the Great Depression that followed had a profound effect on the American psyche for the next fifty years. The story of the 2000s is very much the story of the 1920s—namely, extreme excess on the part of an unregulated financial system—and it is worth re-examining that story within the context of what we have experienced over the past forty years.

Those Who Cannot Remember the Past

The 1920s began with a rather steep recession in 1920-1921 followed by a speculative bubble in the real-estate market. The real-estate bubble burst in 1926 and was superseded by a speculative bubble in the stock market. There was a mild economic downturn in 1927, a brief recovery that same year, and another mild downturn in the summer of 1929. Then the stock market bubble came to a dramatic climax in the fall of 1929. (Galbraith Friedman Meltzer Skidelsky Kindleberger Eichengreen Kennedy)

The Crash of 1929 began on October 24—a day that became known as Black Thursday—when the stock market dropped dramatically in the morning and recovered somewhat in the afternoon. While prices rallied on Friday, there were two more black days to come. When trading resumed after the weekend, the Dow fell by 13% on Black Monday and it fell an additional 12% the next day which became known as Black Tuesday. There were rallies that followed, but, overall, the stock market lost 80% of its value from its high in 1929 to its low in 1932 and the Dow fell by almost 90%.

The Great Depression of the 1930s

As stock prices fell in the fall of 1929 the mild recession that had begun in the summer became severe, and a banking crisis began in the fall of 1930. From 1929 through 1933 the economy experienced a major deflation as consumer prices fell by 25% and wholesale prices by 30%. In the meantime, 12.8 million people found themselves unemployed as output fell by over 30%, GDP fell by 46% , and the rate of unemployment jumped from 3.2% to 24.9% of the labor force. The banking crisis reached its climax in 1933 when over 4,000 banks and savings institutions went under in that year alone. By the time the crisis came to an end over 10,000 banks and savings institutions had gone out of business along with some 129,000 other businesses, and we were in the depths of the Great Depression. And just as happened in 2008, the financial crisis that started in the United States spread throughout the rest of the world. (Kindleberger)

The depression lasted more than ten years. There were still 8.1 million people unemployed in 1940, and the unemployment rate did not fall below 14% until 1941. It wasn't until 1943—when the economy was fully mobilized for World War II—that the unemployment rate finally fell below its 1929 level, and by then the United States had increased the size of its military by over 8.5 million soldiers. In other words, we did not completely solve the unemployment problem created by the Great Depression until we were fully mobilized for World War II and had drafted a number of people into the military comparable to the number who were unemployed in 1940.

What Went Wrong

It was clear to most people at the time that the cause of the problem was rampant speculation in the stock market financed by expanding debt. In fact, the debt created by the financial system during the 1920s had grown to unreasonable levels in all areas, not just in the stock market. This debt was unsustainable, and the stock market crash was just the trigger that set in motion a set of forces that, in the face of this debt, brought down the entire economic system. (Fisher Pecora)

When the stock market crashed, the value of stocks that provided the collateral for speculative loans fell. This led to a panic in the financial sector as financial institutions tried to cut their losses by recalling existing loans and refusing to make new loans. When the banking crisis began in 1930 the financial system simply froze, and credit became unavailable. This forced debtors whose loans were called or who could not refinance their loans when they came due to sell the collateral underlying their debts as well as other assets in order to meet their financial obligations. These forced sales of collateral and other assets, in turn, caused asset prices to fall throughout the financial system, and debtors began to default as the value of their assets fell below the value of the loans they had to repay. (Fisher)

As the panic grew, the rise in uncertainty and the heightened sense of fear and pessimism toward the future exacerbated the situation. The demand for such things as new homes, automobiles, and other durable goods fell as households became reluctant to commit to such purchases or, for lack of credit, were unable to do so. (Mian) At the same time, businesses that were unable to finance their inventories and payrolls as the demand for their output fell were forced to cut back their operations and layoffs began. As output, employment, and household expenditures fell, income fell as well. The result was a vicious spiral downward as falling output and employment led to falling income and expenditures which, in turn, led to falling output and employment. (Keynes)

All of this should sound familiar, given our experience during the recent crisis, since this is exactly the kind of thing that happened in the mortgage market following the bursting of the housing bubble in 2007 and the financial system grinding to a halt in September of 2008. Debt had grown to unsustainable levels by 2007, and when the housing market crashed, the value of the real estate that provided the collateral for real-estate loans began to fall. This led to a panic in the financial sector as financial institutions tried to cut their losses by recalling existing loans and refusing to make new loans. When the crisis reached its climax in 2008, the financial system simply froze, credit became unavailable, and the same kind of vicious downward spiral in output and employment occurred that had occurred following the Crash of 1929 with falling output and employment leading to falling income and expenditures which, in turn, led to falling output and employment.[21] (FCIC WSFC Mian) There was, however, one important difference.

Following the stock market crash in 1929, the lack of federal deposit insurance led to the banking crisis in the fall of 1930 as people began taking money out of the banks in an attempt to protect their savings by hoarding cash. This, in turn, caused the money supply to fall by 25% from 1929 to 1933 which, combined with the fall in output and employment, caused wages and prices to fall as well. The resulting deflation caused the debt that had been accumulated during the 1920s to become an overwhelming burden since this debt now had to be repaid in the face of falling wages, prices, and incomes. As wages and prices fell more rapidly than the debt could be liquidated the real burden of the debt began to increase even as the total debt fell. (Fisher Mian Friedman Meltzer Kindleberger)

In short, because of the unsustainable level of debt that had accumulated during the 1920s and the inability and unwillingness of the Federal Reserve to act, as debtors found themselves unable to meet their contractual obligations the contract system within the financial system began to break down; widespread bankruptcy followed, and the financial system simply imploded. It was the implosion of the financial system—brought on by an unsustainable level of debt combined with falling output, income, money supply, wages, and prices—that brought down the rest of the economy and created the Great Depression of the 1930s. (Fisher Mian Keynes Friedman Meltzer Kindleberger Eichengreen Kennedy) So far at least, we have been able to avoid this kind of implosion of the financial system accompanied by a downward spiral of wages and prices during the current crisis.

The Fall and Rise of Ideology

The vast majority of political leaders, and most renowned economists, entered the 1930s with an unbridled faith in the nineteenth century ideology of Free-Market Capitalism.[22] They were convinced that markets were self correcting; attempts at government intervention would do more harm than good, and that if the economy was just left to its own devices competition in free markets would allow wages and prices to adjust to bring the economic system back to full employment. (Stiglitz) Many even believed the economic system would be made better by the experience of a depression in that depressions weeded out economically inefficient firms and, thereby, made the economy more productive. (Kennedy) This attitude was personified in the infamous advice of President Hoover's Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, to

. . . liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate . . . it will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people. (CP)

The experience of the 1930s provided a shocking dose of reality.

With total output falling by 30%, the unemployment rate increasing to 25%, tens of thousands of business going bankrupt, and human misery increasing at an accelerating rate it was impossible for economists to explain just how the economic system was supposed to be made better by all of this or why the government should not be allowed to intervene to do something about it. There had to be something wrong with an ideological theory that proclaimed it was a good thing for society to be going through what it was going through at the time. The only explanation the theory could offer for the dismal unemployment statistics was that wages were not falling fast enough to bring the system back to full employment. But by 1933 wages had already fallen by 22% in manufacturing, 26% in mining, and 53% in agriculture. There was obviously something wrong with the theory, and all but those with the blindest ideological faith in the miraculous powers of free markets could see that there was something wrong with the theory. [23]

The Crash of 1929 was not the first financial crisis brought on by rampant speculation and reckless behavior in our financial system. As was noted above, there were crises in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, and 1907 that led up to 1929, and the economic fallout from each seemed to be worse than the one that came before. The Great Depression that followed the Crash of 1929 was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and, in response, our political leaders of the 1930s through the 1960s abandoned the failed nineteenth century ideology of Free-Market Capitalism in favor of a pragmatic regime of regulated-market capitalism. As we will see in Chapter 6, this led to the creation of an elaborate system of regulatory and supervisory institutions designed to keep our financial institutions in check. It also led to the elaborate system of government sponsored social-insurance programs we have today—Social Security, unemployment compensation, Medicare, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, and various food and housing assistance programs—programs that were designed to alleviate the sufferings caused by the vagaries endemic in our economic system. These systems actually worked for some fifty years to accomplish their ends, and, in the case of our social-insurance programs, are still working today.

Unfortunately, as new generations replaced old and memories of the 1920s and the Great Depression faded an antigovernment movement began to take hold in the 1970s, and the failed nineteenth century ideology of Free-Market Capitalism became fashionable among our economic and political leaders again. (Frank) As a result, the regulatory and supervisory system that served us so well since the 1930s was systematically dismantled to the point that it was virtually gutted by the early 2000s. This made it possible for our financial institutions to repeat the folly of the 1920s and drive our nation into another worldwide economic catastrophe, just as these institutions had done in the 1920s.

The history of unregulated finance in the United States, and, indeed, throughout the world, has been one financial crisis and economic catastrophe after another. (Kindleberger Phillips Morris Dowd Reinhart Johnson Skidelsky Kindleberger Kennedy MacKay Graeber Galbraith Mian 1819 1837 1857 1873 1893 1907) Given this history, it should be obvious that an unregulated financial system is inherently unstable. Unfortunately, there seem to be a great many policy makers and, indeed, a number of prominent economists who have failed to understand this simple historical fact. (Fox Taleb Dowd Krugman)

Endnotes

[21] Atif Mian and Amir Sufi in House of Debt provide a detailed analysis and comparison of the way in which the fall in asset prices in the face of overwhelming debt affected household behavior in these two eras.

[23] Atif Mian and Amir Sufi in House of Debt provide an extremely cogent explanation of exactly what was, and still is wrong with the theory.

|

|